Fred Valentine felt he was a fieldman for the entire Washington tree fruit industry. (Geraldine Warner/Good Fruit Grower)

Fred Valentine worked as a fieldman for several Washington State fruit entities in his 60-year career, but always felt he represented the industry as a whole.

“He’s been a tireless workhorse for the industry from the very get-go, and he’s still trying to help the industry,” said Fred Smith, retired manager of Wilbur-Ellis Company in Cashmere. Valentine worked behind the scene on problems that many people weren’t even aware of at the time, he added.

Valentine retired at the end of last year and was honored by the North Central Washington Fieldman’s Association, of which he is a former president, during the North Central Washington Pear Day last month. Though an authority of pears, he has a broad knowledge of apple and cherry production, too.

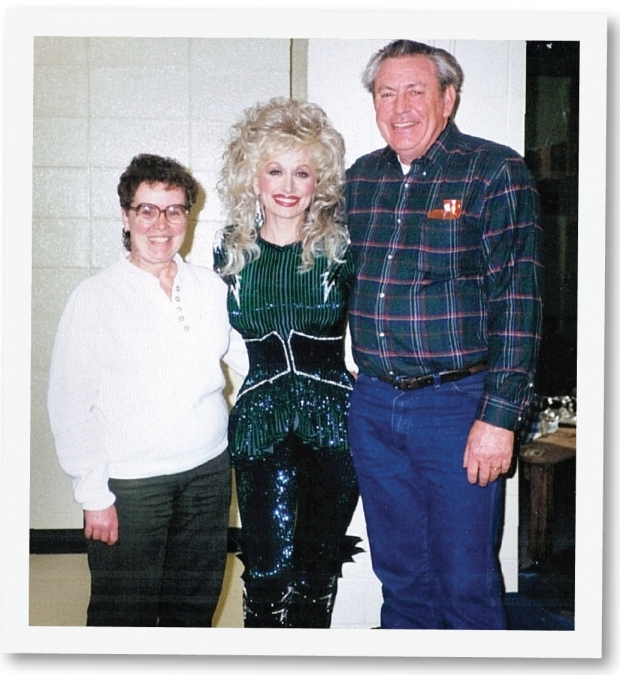

Valentine, 79, is not from a fruit-growing family. He grew up in Tennessee. His father’s older sister was the grandmother of singer and actress Dolly Parton. His father, Theodore Roosevelt Valentine (known as Ted) worked as a logger in the Smokey Mountains and was recruited by the Peshastin Lumber and Box Company in Washington. Valentine was 12 years old when the family left Tennessee for the Pacific Northwest.

His father later went into construction, taking jobs in Montana, Idaho, and Alaska and leaving the family in Peshastin. “He followed the dollar. He was not at home much,” Valentine recalled.

While attending high school in Peshastin, Valentine worked for local orchardist Gene Boswell, who taught him all about planting and growing fruit trees and became a father figure.

Horticulture

After graduating from high school in 1954, Valentine attended Wenatchee Valley College intending to become an engineer. He found he had a greater aptitude for horticulture than engineering and, after a year at college, he went to work as an assistant to Dr. Ted Anthon, stone fruit entomologist at Washington State University’s Tree Fruit Research and Extension Center in Wenatchee.

After three years there, realizing he had no chance of advancement without a degree, he got a job as a fieldman for the orchard supply company Northwest Wholesale, which offered better pay and prospects.

After another three years, he went to work as a fieldman for Blue Star Growers in Cashmere, where he stayed for more than 30 years. In 1968, at the behest of Blue Star manager Jerry Kenoyer, Valentine bought a small orchard so he could better understand the impacts of the recommendations he was giving growers.

“I always got along with growers.” he said. “I always felt that it didn’t make any difference to me whether the grower was in Cashmere, Peshastin, Oroville, or Brewster. My boss asked me, ‘How come you go up there all the time and give advice?’ I said, ‘I learn four times what I give. You benefit more by traveling than by staying at home.’”

In the early 1980s, while at Blue Star, he was contacted by Dryden grower Darrel Caudle, who discovered a new apple variety in his orchard.

Valentine became part of a group of industry people who commercialized the variety, which was initially called Carousel and later renamed Cameo. It was one of the first niche apples to come to market.

Cashmere grower Randy Smith said that although Cameo never became a major variety, it helped start a cascade of new cultivars. “It got people thinking outside of Red, Golden, and Granny. Fred was working on that before Fuji and Gala became popular.”

In 1992, Valentine left Blue Star to work for Wells and Wade, which had been acquired by Dole Fruit Company. Dole came into the tree fruit industry with the goal of being a major player in the industry and was accomplishing all it set out to do, he said. It had warehouses in Wenatchee and Chelan that were both full. But a corporate-level decision to sell the business had Valentine looking for a new position.

Recruit tonnage

His next job, at Stemilt Growers Inc., was to recruit tonnage, meaning he was to find growers who would take their fruit to Stemilt.

“When you get your feet underneath the table drinking coffee with the guy and his wife, you’re on your way,” legendary Manson fieldman Mel Crowder told him. And he was right, Valentine found. He brought Stemilt an additional 15,000 bins of fruit for each of the first two years, and another 15,000 to 20,000 after that, for which he was paid commission as well as a salary.

Valentine worked for Stemilt for five years and then joined Van Well Nursery in Wenatchee as a horticulturist, working alongside Pete Van Well senior. The nursery guarantees replacement of trees that don’t grow, and Valentine’s work included checking on problems that growers reported.

The two men felt they made a good team.

“Fred knew the horticultural practices from experience of being out in the orchards and working with the growers, and I knew more of the growing of the trees aspect—some of the things that cause trees to die,” Van Well said.

When they went out to check on trees, Van Well would examine the trees while Valentine would look at the orchard overall to see what might be affecting growth.

“Between the two of us, we got a pretty good idea of what caused the problem,” Van Well said. “Maybe it wasn’t the tree. Maybe it was some cultural practices. I learned a lot from Fred.”

Valentine retired from Van Well at the end of 2014, his only regret being that he won’t be involved in bringing to market some of the new cherry varieties that are being commercialized. But Van Well said he wants Valentine to remain involved in the nursery even in his retirement. “He just can’t quit,” Van Well insisted.

Though his career has taken many turns, Valentine is happy with how it turned out.

“The people I’ve worked with have been so kind to me that they’ve made me what I am today,” he said. “If I had to do it over, I can’t really say that I would do it differently. I would do it exactly the same.” •

——–

Leading Hort through industry’s worst crisis

The unsuspecting Fred Valentine felt it was an honor to lead the industry when he was named president of the Washington State Horticultural Association in 1989. But that was the year the Alar crisis hit the industry after CBS broadcast its infamous 60 Minutes program falsely describing the growth regulator Alar (daminozide) as “the most potent cancer-causing agent in the food supply.”

When growers were accused of putting children’s health at risk, Valentine was incensed by the injustice. He was particularly upset that the program included footage of a pediatric cancer ward, implying that children were in imminent danger.

Valentine was more inclined to believe those who claimed that a person would have to eat tons of apples each year for a lifetime before there was any cancer risk from Alar-treated apples, and went to Washington, D.C., to lobby on the industry’s behalf.

Presiding over the Hort Association during the Alar crisis is not one of his happiest memories. Consumers lost confidence in apples and growers lost hundreds of millions of dollars. “It was horrible,” he recalls.

He expressed hope that, for the industry’s sake, he would go down in history as serving during the hardest time any hort president ever did or will.

As retiring hort president, he asked friend Janie Countryman to organize the annual meeting banquet.

Countryman promised something special, which fueled a rumor that Valentine’s relative Dolly Parton would attend. All the tickets were snapped up and another 200 people were on a waiting list. In place of Dolly, a posse of fruit industry notables surged into the room to do a skit called “The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly,” which involved dancing and galloping around the ballroom on fake horses to the thumping beat of “Reach” by Martini Ranch. They eventually overcame CBS (played by Bob Gix) using beating trays, pressure testers, and other fruit paraphernalia as weapons.

“It was the funniest thing,” recalled Valentine, who was relieved to end his year in the spotlight with some levity.

He served, less eventfully, on the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission, which he chaired in 1991. He was a member of the Fresh Pear Committee’s research subcommittee from 1990 to 2000. He also represented the pear industry for 20 years on the board of Tree Top, the fruit-processing cooperative.

Leave A Comment