Photos courtesy of Bhaskar Bondada

A shrivel is not just a shrivel.

Of the various types of shrivel impacting grape quality, sour shrivel is especially unwanted because it renders the fruit unsuitable for winemaking.

The disorder, found in vineyards around the world, is known by several names. In California, researchers have begun calling it SAD for sugar accumulating disorder to distinguish it from other shrivels; Washington State University’s Dr. Bhaskar Bondada coined the term “sour” to stand for suppression of uniform ripening. Sour also aptly describes the taste of berries exhibiting the disorder.

Grapevine physiologist Bondada says it shows up every year somewhere in the wine grape growing regions of Washington State and also has been growing in significance in Canada’s British Columbia.

Berry or sour shrivel, which negatively impacts winemaking, is not to be confused with other types of shrivel where affected grapes can still be used for making certain styles of wine depending when the shrivel comes on, Bondada said.

Sunburn—Close examination of sunburned berries shows fruit to be lighter in color than healthy berries. Berry shape is normal and fruit flesh structure intact. However, the waxy surface of the berry is often damaged from the sunburn.

Dehydration—Generally occurs before or after veraison due to water stress or mechanical injury to the cluster framework, girdling the cluster and cutting off supply of water and nutrients to berries. Conversely, the ripening disorder entailing dehydration is commonly observed during advanced stages of ripening, becoming more conspicuous prior to commercial harvest. The dehydrated berries look like golf balls with dimple formations, despite having no injury to the cluster framework.

Bunch stem necrosis—Necrosis is apparent along the bunch stem, rachis or peduncel. Necrosis girdles the area, restricting flow of sugars, water, and nutrients to the fruit. Berries take on a raisin appearance, and the flesh is collapsed.

Berry/sour shrivel—Fruit looks like a deflated soccer ball, and the flesh is collapsed. Fruit is flaccid, low in color, and tastes sour, acidic, and off-flavored. The berries easily fall off the stem when touched. But, despite the collapsed flesh, the seeds remain healthy. “Even the birds don’t like the sour shrivel berries and leave them alone in the vineyard,” Bondada said.

Frustrating disorder

The sporadic disorder is a trying one, Bondada said. He spent several years, along with other researchers, looking for clues to the disorder’s cause. “The frustrating part in following shrivel is that we’ll tag the vines that are showing symptoms, and the next year the same vine is healthy, making it hard to conduct experiments,” he said. “No particular pattern of occurrence could be deduced from its distribution in the vineyard.”

In some wine grape blocks in the state, up to 40 percent of the clusters have shown symptoms. Rick Hamman, viticulturist for Hogue Ranches and Mercer Estates, said that in a young, Cabernet Sauvignon block, the grower had to drop half of the crop due to berry shrivel. In another Grenache vineyard, sour shrivel caused a 40 percent crop loss.

“It’s a moving target,” Hamman said. “It’s there one year and not the next.”

It’s an expensive disorder, because workers must inspect clusters before harvest and cut out the bad berries.

Effect on fruit quality

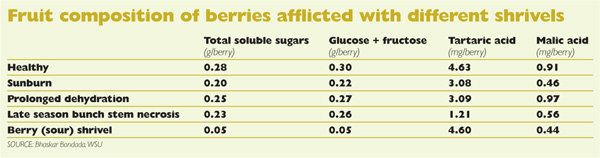

Bondada has studied sour shrivel’s effect on fruit quality in comparison to other types of shrivel. It’s not a pretty picture.

In a detailed look at sour shrivel in Grenache last year, Bondada found Brix to be significantly lower in sour shrivel berries than in healthy ones. He also found lower levels of glucose and fructose, pH, potassium, and malic acid. Higher levels of tartaric acid and tannins in comparison to healthy berries were also found in the sour shrivel fruit. Not surprisingly—because of the failure to undergo the ripening process—total anthocyanins of the sour shrivel fruit were significantly lower than the healthy anthocyanin level (474 milligrams per liter compared to 647).

“The clusters are not suitable for making wine,” he said. Fruit from the other disorders (sunburn, dehydration, or bunch stem necrosis) still have some desirable fruit characteristics and can be used to make some types of wine. “But not sour shrivel. It’s one that you don’t want in your vineyard.”

Good, bad, and ugly

Not all the fruit on afflicted clusters show the symptoms of sour shrivel. Rarely is the whole cluster affected, he said, adding that symptoms are typically found at the bottom of the cluster. “If the whole cluster is affected, then it means you’re losing a lot of crop.”

Bondada found three types of berries in cluster showing sour shrivel—relatively healthy berries (the good) that were only two or three degrees lower in Brix than normal berries from a healthy cluster. No significant differences were observed between healthy and healthy shrivel berries in tartaric acid or pH levels.

“But then you have the bad, which are berries lighter in color. And then there’s the ugly—flaccid, sour-tasting berries,” he said.

Red and white varieties are both affected by the disorder. Bondada has seen sour shrivel in the white varieties of Sauvignon Blanc, Chardonnay, Semillon, and Riesling. In reds, it’s been found in Washington in Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, and Petite Syrah.

“Among the red varieties, Cabernet is the poster child,” he said. “Every year, we see it in Cabernet blocks somewhere in the state.”

Bondada said that the latest victim is Grenache, adding that he’d never seen sour shrivel in Grenache until this past year.

Scientists believe that because the sour shrivel fruit are not getting water and sugar—but the seeds are normal—that the disorder is initiated after veraison.

Bondada adds that by using fluorescent dyes and high-powered microscopes, scientists can examine cell structures within the flesh and other vegetative and reproductive parts of the grapevine. The fluorescent dyes have shown that sour shrivel berries lose membrane integrity of their juice cells, the tiny bags that accumulate sugars and acids.

Bondada shared his findings during the annual meeting of the Washington State Grape Society.

Leave A Comment