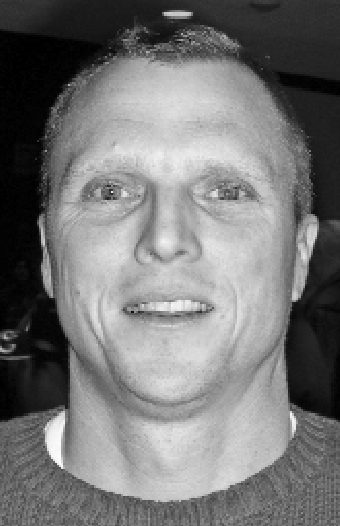

Paul Carter

Kyle Mathison Orchards

Like a swinging pendulum, powdery mildew can cause cherry growers to over-react after a significant outbreak. In their zeal to banish mildew from the orchard, growers must be careful they don’t change cultural practices to the detriment of fruit quality and production. The “perfect storm” for cherry mildew occurred two years ago in a Wenatchee, Washington, cherry orchard, resulting in a million-dollar loss for the grower.

Paul Carter of Kyle Mathison Orchards said conditions in the orchard created a “Taj Mahal” for cherry mildew. Yields in the orchard were 14 to 16 tons to the acre; trees had big, green foliage; and the late-season Canadian varieties of Sweetheart and Staccato had a long growing season, harvested in August and September.

The undertree sprinklers used to cool the trees in hot, summer temperatures also increased humidity within the canopies. “This was the perfect habitat for mildew,” Carter said during a discussion about cherry mildew at the recent Cherry Institute meeting in Yakima, Washington.

He explained that although their goal in 2003 was to spray the orchard every 10 to 14 days, rotating fungicide products for resistance management, there were a “couple of gaps—one interval was a 16-day window, and one was a 14-day gap.” With the late-season varieties, fruit is exposed to a much longer window than cherries harvested in early July. “The result of the gaps was a million-dollar mildew loss,” he said.

Overcorrection

In their quest to prevent and eliminate mildew the following year, Carter said they overcorrected and implemented strategies that went too far, reducing tree vigor, fruit size, and luster. “We had an early, concentrated harvest,” he observed, adding that the harvest was out of sync with neighboring orchards.

“We reduced luster on our clusters and may have grown stems shorter than normal.” They also switched from undertree cooling to drip irrigation. “We were deathly afraid of creating another mildew habitat, so we went to drip. But I know the trees would have been aided during the hot summer with cooling.” Carter adds that they also experimented with compost teas, applying the teas in one trial every ten days. He believes that the shine on fruit was diminished in the tea trial. Though last year’s crop wasn’t a stellar success, Carter admits that they “did a lot of good things” in their quest to wipe out mildew.

“We were religious about our spray intervals, keeping them every seven to ten days. We used new fungicide products and rotated them wisely.” They focused on cultural practices, removing scaffolds that interfered with spray coverage. “We scouted and scouted,” Carter said, noting that they looked for mildew on suckers high in the tree, on clusters, and on foliage. They monitored Bing trees within the orchard that had already been harvested to help track disease pressure.

Spray speeds were slowed down to two miles per hour, and spray gallonage was increased to 300 to 400 gallons per acre when clusters filled out. Fungicides were applied right behind irrigation sets. “We had virtually no mildew,” he said. “But there were challenges. A few spray intervals were stretched, and we needed more gallonage in some applications.” He notes that they’ve had good results with oils; however, growers must use oils very carefully in warm temperatures.

Oils have been associated with tree defoliation and fruit damage when applied later in the season during warm temperatures. Growers must find a balance within their orchards, keeping yields and quality at profitable levels while preventing mildew outbreaks. Increased gallonage used in sprays and tight intervals will help orchardists stay on top of mildew disease.

Leave A Comment