Balaton tart cherries.

By Dick Lehnert / Good Fruit Grower

Michigan has a tall reputation in the cherry business, but producers come up short on price. According to National Agricultural Statistics Service figures, the U.S. price for fresh tart cherries increased 91 percent from 1980 to 1999—but Michigan sells mostly processed tart cherries, and that price went up only 3 percent. During the three years from 1998 to 2000, the average U.S. price for fresh sweet cherries averaged 59 cents a pound—but Michigan growers averaged only 26 cents.

Growers in Washington got 79 cents, New York 83 cents, and Pennsylvania $1.18. So, the questions seem to be, how can Michigan growers put more products into the fresh category, and how can they get more for them? Greg Lang and his colleagues Bridget Behe and Jennifer Sowa in Michigan State University’s horticulture department have been looking for answers to those questions the last three years.

They reported on their latest work at the Great Lakes Fruit, Vegetable and Fresh Market Expo in December in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Part of the answer, they think, lies with a desirable “sweet tart” cherry called Balaton. Unlike the red-skin, clear-flesh, clear-juice Montmorency cherry that most Michigan tart cherry growers produce for pie filling, Balaton is a dark red cherry that is sweeter than tart but tarter than traditional sweet varieties. Taste tests show consumers like the taste.

From Hungary

MSU cherry breeder Amy Iezzoni brought Balaton to the United States from Hungary. During the 1990s, as she worked to create other varieties, a few growers began planting Balatons. There are about 100,000 Balaton trees in Michigan now, Lang said, and it’s time to try to sell them for a premium. He and his colleagues surveyed retail produce markets in 2002, looking to see what they were getting for sweet cherries.

The markets were segmented into five groups: large-volume chains, regional chains, local chains or independents, specialty stores, and farm markets. The average seasonal price per pound in these five groups in 2002 was $2.88, $3.37, $3.40, $5.21, and $2.65 for red sweet cherries. Premium yellow Rainier cherries commanded $1.20 to $1.75 more in all markets except the farmers market.

They decided to test market Balatons in specialty stores where red cherries sold for $4.99 a pound in 2002 and $3.99 a pound in 2003 and 2004. This past year’s trial was scaled to sell two or three tons across a half dozen retail outlets. The regional Public Broadcasting Service cooking show A Fork in the Road with Chef Eric Villegas featured the Balaton cherry story as the first show of the fall 2004 season, highlighting the unique qualities of Michigan’s “sweet tart” cherry and its uses fresh, frozen, and packed in sweetened cherry juice.

The Balatons successfully sold in clamshells in Whole Foods stores at sweet cherry prices. The fresh Balaton fruit helped drive marketing and sales of related processed products, like wine and premium preserves and salsas made from them, Lang said. What’s ahead in 2005? No contracts have been signed, but the goal is to sell about 20 tons of Balatons this coming year in selected stores.

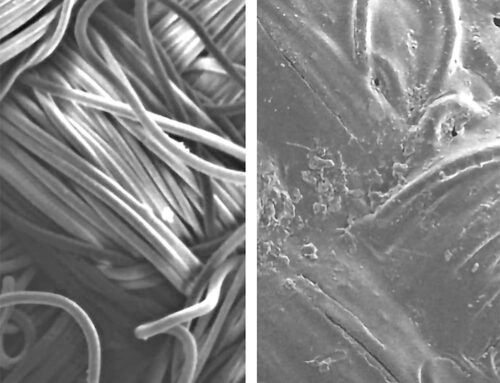

Lang also reported a 2004 postharvest study that demonstrated “excellent postharvest shelf life” for hand-harvested fresh Balaton fruits, but significantly higher—two to seven times as much—fruit damage and decay from mechanically harvested fresh Balaton fruits. “We can’t use current mechanical harvesting technology,” he said. Better harvesting equipment needs to be developed, and canopy management methods need to be defined.

On the up side, the pricing works out to give growers about $2 a pound for packaged Balatons that sell fresh. There are IQF (Individually Quick Frozen), juice, and winery markets for those that don’t make the cut, and prices are attractive enough to make hand harvest worthwhile, Lang said. Electric eye sorting is still being developed. Lang also reported a sensory evaluation study conducted last summer comparing fresh sweet cherries on dwarfing rootstocks from MSU test orchards with cherries from one of Washington’s largest cherry packers.

Washington Bing cherries were larger and sweeter than Michigan Ulster cherries, Lang said, but consumers rated the Ulsters equally desirable in color and texture and slightly higher in flavor and overall impression, with twice as many favorable comments as for the Bings. They agreed they would expect to pay 15 cents more a pound for the Ulsters than the Bings. The MSU Rainiers grown on dwarfing rootstocks were rated equal or superior to the Washington Rainiers for color, texture, flavor, and overall impression, with five times the number of favorable comments on appearance for the Michigan Rainiers.

Leave A Comment