Trapping prohibited

In Washington State, the use of body-gripping traps or snares has been prohibited for animals other than mice since 2000 when voters passed Initiative 713. Box-type cages are still legal. Repeated legislative attempts to allow trapping of rodents like moles and gophers have been unsuccessful. Such traps can legally be sold in the state, but body-gripping trapping violations can be charged as a misdemeanor.

In a recent University of California study that examined pocket gopher control methods, the most effective control was trapping plus fumigation, killing up to 90 percent of the gophers. Pocket gophers are particularly damaging to young orchards and vineyards. They can cause extensive damage and even kill trees or vines by girdling and pruning roots underground.

The dirt mounds left behind can interfere with tasks like mowing, spraying, and harvesting, causing equipment to bounce and misdirect herbicide spray nozzles or bruise fruit. The rodents have also been known to gnaw on plastic irrigation lines. Pocket gophers are found only in the Western Hemisphere and occur throughout the western two-thirds of the United States. While there are several tools available to control pocket gophers, Roger Baldwin, UC Cooperative Extension Wildlife Pest Management advisor, wanted to compare several treatments side by side for efficacy and cost effectiveness.

He found a heavily gopher-infested vineyard in California’s Sonoma County and compared three methods: trapping, followed by fumigation with aluminum phosphide pellets; baiting with strychnine-treated milo bait; and using a gas explosive device that combines propane with oxygen called the Rodenator.

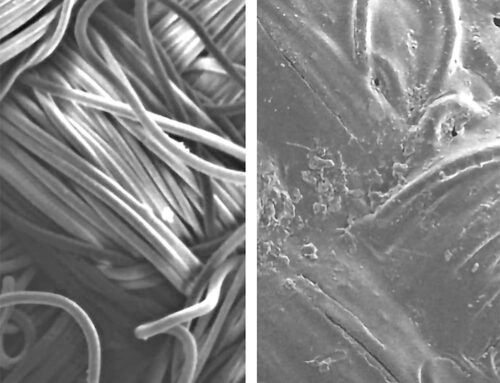

“There’s been a stigma out there that trapping is too labor intensive and not really effective,” said Baldwin. “But in our study, we found it to be very cost effective. And, in fact, it was the most effective method, in part, because of a new trap called the Gophinator that outperformed the older Macabee trap by catching the larger-sized gophers that used to be missed.” The new trap was designed and patented by Steve Albano, owner of Trapline Products. Albano is the son of orchardists Howard and Jean Albano of Cuyama Valley, California.

“The worst thing you can do when controlling gophers is use a rusty, old trap that pinches but doesn’t catch them,” Albano said. “Now, instead of a trapped gopher, you’ve got one that’s trap shy, and knows how to avoid the trap. If you can get the population under control so that it’s not a breeding population, and then keep it under control, it’ll be more manageable even if gophers come in from the edges.”

UC study

Baldwin established a replicated trial in the Sonoma County vineyard, which had an estimated gopher population that averaged 60 gophers per acre—among the highest activity one would expect to ever encounter, he said. Gopher populations within the treatment blocks were indexed by counting fresh gopher mounds and feeder holes in the plots per treatment block.

For the trapping plus fumigation treatments, plots were first trapped with Gophinator traps. If a gopher triggered or plugged a trap without getting captured, the tunnel system was flagged and then fumigated with aluminum phosphide. Gophers that spring traps without getting captured can become trap shy and are more difficult to capture.

A self-dispensed probe was used for the baiting treatments, and the label rate was applied twice per burrow system. The Rodenator, manufactured by Meyer Industries, was used to treat the gas explosive plots. After treatments were completed, the blocks were reevaluated for gopher activity. A second round of treatments, applied in the same manner, then followed.

Baldwin notes that a grower could go through as many times as it takes to eliminate gopher activity, but for the study purposes, he had to set a limit on the number of treatments. “It could be that if a grower went through another time (three times) and really got population numbers down, it would reduce costs in the future,” he said. “But we really don’t know that from our current results.”

Efficacy and costs

Based on his study, gopher control or mortality from the Rodenator ranged from 0 to 55 percent; baiting ranged from 30 to 56 percent; and trapping plus fumigation from 74 to 90 percent. “To be effective, control measures need to result in a minimum of a 70 percent reduction in plots with gopher activity; values of 80 to 90 percent are preferable,” Baldwin stated in his research report.

He said that in the trapping plus fumigation treatment, fumigation was needed in less than half of the treatments. He believes that both methods would likely be effective as stand-alone treatments. In addition to efficacy, Baldwin wanted to learn about the time and cost involved with the different treatments. He recorded average time involved to apply each treatment, the labor involved, and the material costs.

Trapping plus fumigation was the most cost-effective treatment. Although per- acre costs of the various treatments should be considered as estimates because each site and labor crew will differ, Baldwin found that treatment costs on a per-acre basis were: • Trapping plus fumigation done by professionally trained rodent control employee—$252 per acre • Rodenator done by professionally trained rodent control employee—$396 per acre

•Baiting done by a farm labor crew—$420 per acre “An additional round of treatments could have resulted in greater absolute control values, although additional treatments would add additional costs to control efforts,” he stated.

“This is of note, as baiting, and in particular, the Rodenator treatment, have the potential for slowing reinvasion rates due to the destruction of gopher burrow systems by the Rodenator and the residual bait remaining in vacated gopher tunnel systems.” He said that initial results hinted that the Rodenator treatments may be reducing gopher populations for several months posttreatment, although more follow-up is needed.

Future work

Baldwin will continue to compare gopher trapping and trapping plus fumigation treatments in 2010 to learn how the treatments work independently. He’s also looking at using attractants to increase catches with traps. “We can catch a lot of gophers without scents, but would we catch even more using attractants?” he asked.

He also wants to learn more about long-term control and the economics of getting populations down to very low numbers combined with control costs of future years. He plans to collect additional data on the Rodenator to look at long-term residual effects. •

Leave A Comment