Ron Moorse, a foreman from the Bureau of Reclamation, shuts the Roza Irrigation District down the morning of May 11, 2015, to manage drought conditions in Washington’s Yakima Valley. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

Floating pumps. Recycling sewage for irrigation. Tens of millions of dollars in federal grants for water projects.

Irrigation districts in the western United States are taking extensive measures to provide fruit growers with more water during drought years.

However, growers will foot a lot of the bill through higher rates.

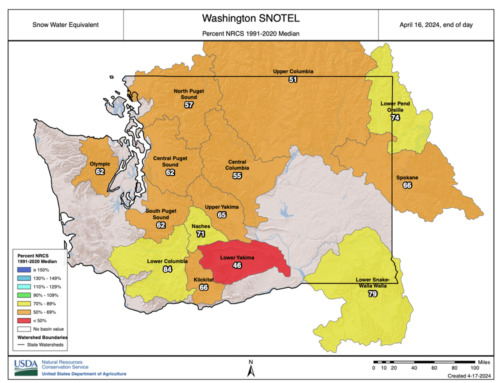

California growers are bracing for their fifth straight drought year. In the Pacific Northwest, heavy snows in December eased drought concerns, but how much water growers will have for irrigation remains uncertain, following a year of record heat and low snowpack.

The 2015 irrigation season saw irrigation districts with junior water rights curtailed to 47 percent of normal allotment.

Through mid-December, the Yakima River Basin’s five mountain reservoirs in central Washington were half full, a little above average for that time of year.

However, 66 percent of Washington was still in some level of drought, while about half of central Washington’s fruit growing region was in an “extreme drought,” according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Drought Monitor.

“It is way too early to panic or to celebrate,” said Chad Stuart, the Yakima field office manager for the federal Bureau of Reclamation.

Planning ahead

Irrigation districts are trying to take action now.

The junior-rights Roza Irrigation District, based in Sunnyside, Washington, plans to participate in a permanent federal Bureau of Reclamation project to pump an extra 200,000-acre-feet of water from mountain reservoir Lake Kachess as part of the Yakima Basin Integrated Plan, a 30-year, $4 billion effort to improve water management for both fish and irrigators.

Irrigators in the Wenatchee River Watershed have a similar, if smaller, series of proposals.

Early cost estimates put the Lake Kachess idea at $200 million, which would be shared by participating irrigation districts, said Scott Revell, Roza District manager.

Any increase would be on top of the rising costs irrigators already pay.

On Dec. 15, the Roza board of directors decided to increase 2016 assessment rates from $134 per acre by $48, a 36 percent jump.

Nearly all of that hike, $43 of it, will be used to repay the district’s drought fund, which spent $1.8 million in 2015 on water leases, pump backs and other drought-related costs, plus $1.35 million in design and permitting work for a proposed emergency floating pump on Lake Kachess that would have provided additional water this year.

The Roza board scrapped that emergency plan after cost estimates surged to $77 million, but that doesn’t mean irrigators are confident in the coming water supply.

“We’re not convinced we’re out of the woods yet for 2016,” Revell said.

The Roza received only 47 percent of its full supply in 2015 and shut off water completely for three weeks in May.

Roza’s 72,000 acres on the eastern side of the Yakima Valley are 80 percent “high-value” crops, such as tree fruit, grapes and hops.

The Washington Department of Ecology has awarded Roza a $292,000 grant for an emergency drought well.

The agency allowed its statewide drought declaration to expire at the end of 2015.

But, if necessary, the state is preparing to declare a drought emergency earlier this year than the May declaration of 2015, Maia Bellon, state Department of Ecology director, told growers at the Washington State Tree Fruit Association’s Annual Meeting in December in Yakima.

A drought emergency would free up some of the $16 million emergency funds set aside for drought relief projects and fast-tracking emergency well permit applications. The state spent $5.6 million of that in 2015.

Switching from tree fruit and grapes to annual crops would hurt the whole economy, not just growers, said Jon DeVaney, president of the Washington State Tree Fruit Association based in Yakima.

Jobs would suffer and the overall value of agricultural production would drop because perennial crops require more labor and sell for higher prices, he said.

“It’s important for our local economy because tree fruit is a high-value crop,” he said.

The situation in California

In early December, California officials warned State Water Project customers they will get 10 percent of their full allotment if the irrigation season starts with current conditions, half what they received in 2015, according to a Dec. 1 news release from the state.

The State Water Project delivers water to two-thirds of California’s population through 29 urban and agricultural suppliers throughout the state.

As a result, irrigation districts there also are turning to extraordinary ideas.

The Del Puerto Water District in Stanislaus County has teamed up with the cities of Modesto and Turlock to pipe 30,600 acre-feet of recycled municipal wastewater under the San Joaquin River and into irrigation ditches for fruit and almond growers. The project, in the permitting process now, would start delivering water in 2018.

The proposed cost: $100 million.

To pay for it, farmers would see their water rates increase by up to $250 per acre-foot during the first 30 years, according to news coverage by the Modesto Bee.

Growers in the junior-rights district received none of their federal rations from the Central Valley Project in 2014, instead paying up to $1,000 per acre-foot on the open market.

Such a project would not fly in Washington because rerouting wastewater from cities for irrigation would divert water from the Yakima River and water users downstream, Revell said.

In fact, only coincidence allows Del Puerto to get away with it, said William Wong, project manager for the city of Modesto.

The city’s wastewater permit effectively prevents discharging into the San Joaquin during the spring and summer anyway. Instead, the city used it to irrigate 2,500 acres of cattle feed land leased to a rancher.

“We ended up being lucky, and Del Puerto is even luckier,” he said. •

– by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment