A Washington State University horticulture researcher has found a new use for a familiar compound. Spraying pear trees with glycinebetain (GB) four weeks prior to picking allowed farmers to leave fruit on trees longer and to significantly improve its firmness when it came out of storage.

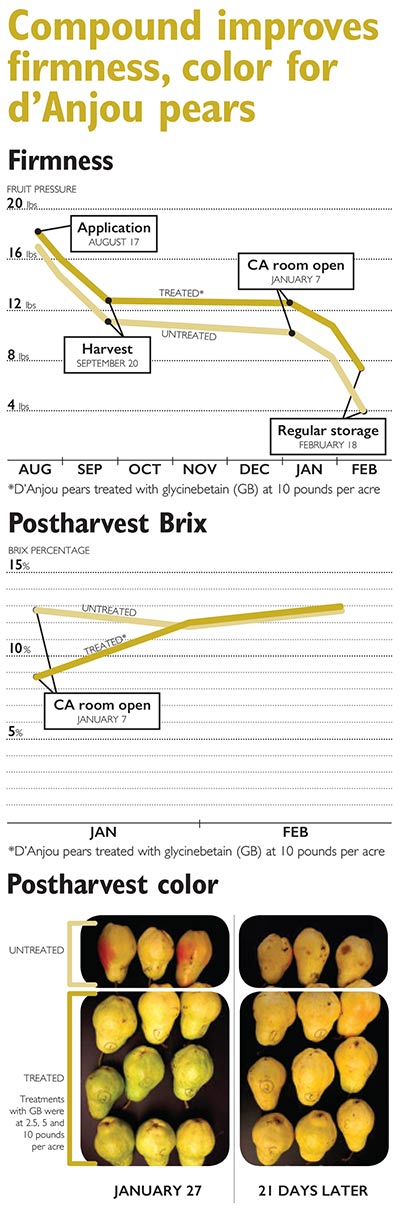

A study found that d’Anjou pears sprayed with glycinebetain (GB) before harvest were firmer and greener than untreated pears when they came out of storage. While the Brix level on the treated pears was initially lower on release from storage, it rose to match the level of untreated pears within a few weeks. Source: Washington State University (Jared Johnson/Good Fruit Grower Illustration)

Dr. Amit Dhingra, a WSU horticulture department associate professor, had growers in Washington’s Wenatchee Valley spray their pear trees with a compound normally used to control cracking in sweet cherries. Marketed as Bluestim, Greenstim and Verdera, it is an osmoregulator, used to control moisture loss in crops.

“What it really does,” Dhingra said, “is prevent the degradation of chlorophyll.”

Dhingra’s quest began one day while he was standing in a Cashmere Valley orchard having a conversation with a grower. The grower asked if there was a way to keep pears greener.

After giving the question some thought, he remembered working with GB earlier in his career. Initially, he was unaware of its labeled use; after he found out, however, he quickly secured a patent for WSU for pre- and postharvest applications.

Dhingra’s growers sprayed the compound onto trees at 2.5, 5 and 10 pounds per acre two weeks prior to harvest. Testing for fruit pressure and firmness at harvest, they saw no difference between treated and untreated d’Anjou and Bartlett pears.

Improved freshness

But when he and his team opened the controlled-atmosphere (CA) storage rooms in January, they were confronted with “an amazing difference.” Untreated pears showed a 34 percent decrease in firmness while treated pears showed only a 4 percent decrease. “In effect,” he said, “ripening occurred under suspended animation. But when the fruit came out, it woke up.”

Once removed from storage, the treated pears were greener and firmer than the controls. The Brix level was 8° but rose to 12° within two weeks.

The added firmness translates to longer shelf life, he says. Based on fruit pressure, he estimated it can be extended by at least two weeks.

GB delivers other attributes consumers will find attractive, too. One is good color after storage. “We noticed blush in a lot of the control fruit, and this product showed it can help in eliminating it,” Dhingra said. “This may be useful for Granny Smith and Golden Delicious apples.”

David Sugar, now a retired Oregon State University-Medford fruit researcher, discovered another attribute. GB eliminated internal browning after six months in storage at 0.5°C (33°F).

Sugar used Comice pears in his trial and duplicated Dhingra’s fruit pressure results.

Delayed harvest

Another benefit GB brings to pear growers is delayed harvest. When sprayed prior to harvest, it extends the amount of time fruit can stay on trees.

How much time is an open question. Dhingra has anecdotal evidence of a grower who left his pears on his trees an extra two weeks after treating them with GB.

That result will be tested with more research, he said. It’s worth a look because added time on the tree means a longer picking season and the flexibility that brings, as well as heavier fruit.

The longer storage and shelf life means more time in front of consumers’ eyes. Firmer fruit translates to less damage in packing and shipping.

Future research will likely look at what benefits come with postharvest applications as well as larger field trials to evaluate the product’s effectiveness.

– by David Weinstock, Ph.D., a freelance writer whose articles have appeared in Farming, Growing and other publications. •

Leave A Comment