Patrick Archibeque watches bulk packing of cherries. The new technology was installed in time for this year’s cherry season. Nearly all of California’s major cherry packers are using new optical sorting technology. Photo by Melissa Hansen

It’s never easy being a cherry grower, especially this year if you’re a California cherry grower. Cherries there were hit hard by the drought—not from lack of water but lack of winter chill hours.

Cherry production in California was revolutionized more than a decade ago with development of early varieties, like Brooks and Tulare, which are less prone to doubling and spurs when grown in a warm region. Most early varieties also have lower chill requirements. For example, Bing requires 900 hours of chilling compared with 400 hours for Tulare.

In the last decade or so, sweet cherries have been on a rapid growth curve in California, with orchards planted in nearly all parts of the San Joaquin Valley, well beyond the traditional cherry-growing area known as the Lodi district.

Cherries are now one of the highest value crops in Kern County, the southernmost part of California’s fertile San Joaquin Valley once known for oil production. Early season cherries, most of which are exported to Japan and other Asian markets, can fetch outrageous prices. The profitable crop has even enticed growers from 1,500 miles away, like Wenatchee, Washington’s Kyle Mathison, to plant cherry orchards in the county.

“There’s no region that wasn’t impacted.”

—Patrick Archibeque

But for many California cherry growers, 2014 was not a profitable cherry year. In fact, for those who didn’t even pick their cherries, it was downright dismal. Good Fruit Grower visited California in May in preparation for this report.

Tule fog

California’s San Joaquin Valley is known for its tule fog, a mist so dense that the sun can be blocked from view for weeks at a time. In normal weather years, fog occurs 40 to 50 days. But fog needs moisture from the ground to be created, and California, locked in a severe drought since the 2010-2011 season, received scant rainfall last winter.

Fog plays a key role in the winter chill accumulation for the valley’s stone fruit. It blocks solar radiation and keeps temperatures from warming in the daytime, making daytime temperatures 20 degrees colder than otherwise.

“The tule fog just didn’t arrive last winter,” said Patrick Archibeque, chief executive officer of Rivermaid Trading Company in Lodi, California.

Cherries were one of the crops most adversely affected from the lack of fog. The dry winter didn’t help much either.

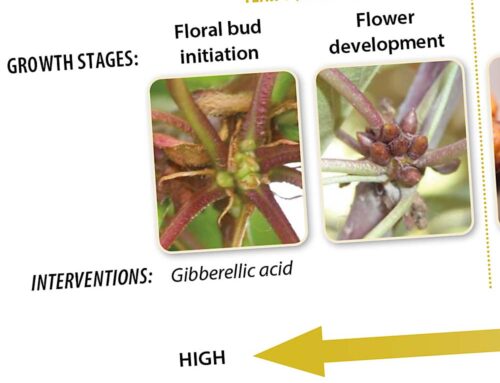

Without enough chill hours to put trees at complete rest or dormancy, bloom was impacted. Low chill is always an issue for cherries grown in the southern district (Kern, Kings, Fresno, and Madera counties), which is warmer than the northern district. But this year, growers throughout the state saw a prolonged bloom period, erratic bloom, and uneven leafing on the tree, resulting in poor fruit set.

The crop was also about two weeks earlier than normal.

Archibeque says the crop was light throughout the state. Rivermaid Trading, a major cherry and pear grower and packer, normally handles about 800,000 boxes of cherries. This year, he expected about a third of a crop.

Few untouched

“There’s no region that wasn’t impacted,” said Archibeque, adding that location and elevation seemed to influence the severity of poor fruit set. “Many times in California cherries, one region will have rain or hail, but there always seems to be a bright spot somewhere. You just can’t find it this year.”

He noted that fruit set seemed to be rootstock dependent. Trees on Mahaleb rootstock appeared to have better fruit set than trees on Colt or Mazzard.

“Those with heavy Mahaleb in their mix are in a much better position,” he said. “And while all varieties performed poorly, Chelan and Garnett seem to have very light crops.”

At O-G Packing and Cold Storage Company, another major cherry packing house in Stockton, only two cherry lines were running in mid-May instead of three. Tom Gotelli, plant manager, said their tonnage would be down about 60 percent.

Based on acreage planted, which is believed to be more than 40,000 acres, California has the potential to hit 12 million 18-pound boxes of cherries, but it’s a number the state has yet to see. Around 8 million boxes are considered a full crop.

For the northern district in the Lodi-Stockton-Linden area, four to five million boxes are considered a full crop of Bing cherries. Industry sources expected the northern Bing crop to come in this season at less than two million boxes and the state’s total crop at about 35 percent of normal.

By mid-May, California had shipped less than half its normal volumes.

“Every perishable crop has narrow parameters that make it work,” said West Mathison, president of Stemilt Growers, Inc., in Wenatchee, Washington. Stemilt has majority ownership in Chinchiolo Stemilt California, a cherry packing facility in Stockton, and Mathison family members have orchards in Kern County.

“For cherries, you want an early start to the season, winters with enough chill hours for fruit set but not so cold that winter damage occurs, and an early spring but one that avoids spring frosts,” Mathison said. “There’s only a narrow band around the globe that meets such parameters.

“We’re near the edge or slightly out of the envelope for cherries in southern California,” he said.

In an interview last year, Mathison said the need for low-chill varieties is forefront. Plant breeders are working to develop them, and a few varieties boasting low chill and resistance to doubling and spurs have been released in recent years, but it takes time for testing before widespread commercial planting. Others are in the works.

New technology

Nearly all of California’s major cherry packers used electronic sorting technology this year, which was timely considering the difficult crop. With the light crop, growers couldn’t afford to color pick their crop and most had to strip pick, which resulted in a wide variance of color, maturity, and size.

It’s this type of year that the new technology will really make a difference.

The new sorters use high-definition cameras or infrared technology to take multiple pictures of each cherry. Sizing accuracy is reported to be from 85 to 98 percent, depending on the equipment manufacturer, and for defect sorting, accuracy is around 80 to 85 percent. (For more information about sorting technology, see “The future of cherry packing,” May 15, 2014, Good Fruit Grower.)

This was the first season for Rivermaid Trading to use optical sorting technology they’ve dubbed “the Oz.” Archibeque said it allowed them to sort all ranges of fruit size and maturity.

“We have 36 exits, which means a lot of different sizes, colors, and grades. If there’s big fruit in the lot, we’ll find it and we’ll be able to sort the quality fruit that’s there.”

Leave A Comment