Michigan State University cherry expert Gregory Lang is trying a retractable roof system over a cherry orchard at MSU’s Clarksville Research Center in south-central Michigan. The steel and cable structure’s roof is tied to a weather station, so it opens and closes automatically. (By Leslie Mertz)

The greenhouse structure at Michigan State University’s Clarksville Research Center is every cherry grower’s dream.

It has a roof that opens and closes automatically with weather conditions, nearly eliminates bacterial canker regardless of pruning time, and promotes bountiful, crack-free fruit that can always be picked at the peak of ripeness.

With the addition of heaters, trees can also bloom and set fruit earlier, so growers can harvest before their competition and when prices are at a premium.

MSU horticulture expert and cherry expert Gregory Lang had the structure installed over an existing 3-year-old block of cherry trees and began researching the benefits in 2012 — a rough year for Michigan cherry growers.

An early bloom coupled with subsequent and severe frost events essentially wiped out the state’s cherry industry before Lang could have the roof installed.

“By the time the roof was completed in May, we had all these trees with dead blossoms, dead buds, bacterial canker coming into all those dead spots, and I was really concerned that the orchard was going to collapse and go down from bacterial canker,” he said. “So here I was with this fantastic covering system, and I was very depressed because I thought all of my trees were going to die.”

Fortunately, things began to look up as the year progressed. “The trees started to come out of all that infection, the temperatures warmed up, we went into a normal summer, the bacterial canker mostly dried up, and the trees started putting out new shoots and recovering,” he said.

Now, Lang is sharing what he’s learned about the system in the years since — both the pros and the cons — with growers.

Roof vs. open air

MSU cherry expert Gregory Lang describes a roofing system during a Clarksville Research Center field day last year. Installed in 2012, the donated system covers about a third of an acre and 225 cherry trees. So far, Lang is pleased with its performance and ability to maintain optimal environmental conditions inside. (By Leslie Mertz)

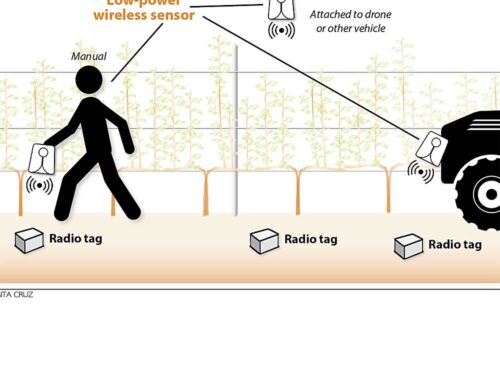

In addition to a retractable, peaked roof, the installation includes a linked weather station equipped with sensors for every condition, including rain, wind, barometric pressure (which can help predict storms as well as hail), and air and soil temperature. The roof can be programmed to operate automatically.

Lang noticed a difference between the trees under the roof and those outside as early as the first year. Even with no crop in 2012, programming the roof to close when it rained kept the trees in the covered section in an optimized environment. Just one of the 225 trees under the roof succumbed to the 2012 freeze and canker event; 5 to 10 percent of the trees outside died. “That was an unexpected benefit of the roof,” he said.

Beginning in 2013, Lang’s group programmed the roof to close in mid-March as a way to capture solar heat and advance the bloom. They settled on March 15 because by then the risk of a heavy snowfall was low; snow accumulation prevents the roof from folding up, and the roof must be opened if temperatures inside get too high.

That year, Lang said, yields were six times higher under the roof than outside. A number of factors played a role: Extreme cold temperatures took a toll on unprotected flower buds outside, and cold and wet weather kept honeybees from flying outside, which hampered pollination. “And to add insult to injury, it rained during harvest, so we lost a lot of outdoor fruit to cracking,” he said.

For an additional comparison, Lang added rain covers over a portion of the outdoor section of the plot to prevent cracking. While the yields were higher than those in the completely uncovered section, they were still only half the yields from the fully covered section.

He attributed the difference between the covered trees outdoors and those inside under the roof to three things: bloom timing, pollination conditions and winter bud damage.

Another interesting difference is that honeybees do poorly under the plastic covers, he said. “Honeybees can find their way into tunnels or under rain covers to get to the flowers, but they navigate with polarized light. Polarized light is disrupted by the plastic, so the bees get disoriented,” he said.

With the retractable system, however, the roof is open on rain-free days when honeybees are active, so they can fly in and out without any problem.

Growers take a look at the cherry trees growing under the retractable roof system, which was retracted at the time. (By Leslie Mertz)

Following 2013, Lang felt quite confident that the roof would optimize the environment and alleviate rain cracking, winter damage to the buds, and poor pollination. The next year threw him a curve.

“In 2014, we closed the roof early like we planned and we bloomed early, but as soon as we hit full bloom, the weather turned cloudy and cool, and we went a whole week with no sunshine and temperatures that never got above 50 degrees, as can happen here in Michigan, so we had no bees flying,” he said.

Even with the structure completely closed up and the heaters on, the bees stayed put in the hives. “The trees inside eventually got pollinated, but we had a lot of heavy June drop because the flowers were a week old by the time the bees started flying,” he said. Outside, the trees bloomed later in what were beautiful pollination conditions. “So, while I assumed that we could control so much with the roof we couldn’t control a week of cloudy, cold weather.”

Lang has had good results since then, and had even planned this year to close the roof on March 1 based on a review of the increasingly warm weather seen in Michigan over the past decade or so.

“We were going to really push the limit to see how early we could bloom and whether we could get ripe cherries in late May, which I think is feasible,” Lang said. A bad utility-company transformer cut power to the orchard — and the roof motor — in late February, which pushed the timing back a bit, but they were still able to close the roof a few days earlier than in previous years.

Unexpected advantages

As of June 22, 2016, deep red, sweet cherries already filled the Benton trees under the retractable roof in Lang’s south-central Michigan plot. (By Leslie Mertz)

All in all, Lang said he is pleased with the sturdiness of the structure, its ability to open and close automatically, and the level of control it provides over weather conditions. It also is delivering some unexpected advantages, Lang said.

One is the great reduction in certain diseases. Because the system has peaked roofs with gutter-equipped valleys, rainwater sheds from the roof into the gutters and away from the orchard, he said.

The only water the orchard sees from closure in March to opening in November is irrigation water.

“The beauty of that is it almost eliminates bacterial canker spread, and it also eliminates cherry leaf spot, which is something that would otherwise require 10 sprays a season,” he said.

Powdery mildew does appear under the roof, but is not as big an issue as it is under high tunnels. He speculates that’s because the roof is often open and allows for more normal air, light and humidity conditions.

Because the orchard is automatically covered when it rains, pruning is also a more convenient chore. “I don’t have to worry about finding three or four days of clear weather so pruning wounds can heal and avoid getting bacterial canker in the cuts. Now, I can prune whenever I want, even in a rainstorm,” he said.

Likewise, picked-fruit quality is no longer predicated by the weather. “You don’t have to harvest when they’re not fully ripe because you have a storm coming in that could damage the fruit,” he said. “With the roof, if the fruit is going to be perfectly ripe in the middle of three days of rain, you can still schedule your crew to go and pick that crop. It’s a really nice advantage.”

Is it worth it?

Of course, the system is not cheap. The donated system over his one-third acre had a price tag of about $100,000, he said, although economy of scale would no doubt lower the cost per acre for a larger system.

Nonetheless, he said, such an automated retractable roof structure can make sense economically if the grower has a high-value market. For instance, growers in Spain, Tasmania, and South Africa are installing such structures to produce cherries for targeted overseas markets willing to pay as much as $75 a pound.

“If you can get your cherries on the market when there are no other cherries out there, you can name your price for the high rollers that will pay for a good cherry any time of year,” he said.

High-value markets aren’t only overseas, he contended. Specialty grocers, such as Whole Foods Market, will pay a pretty penny for local, sustainably produced fruit that their affluent clientele view as being perfectly ripe and having the best flavor. “If we can sell our locally grown cherries at $8.99 a pound, for instance, that changes the economics of what I can afford to do in my orchard,” he said.

Likewise, if Michigan growers can get their cherries to local markets in the middle of May, rather than the normal mid-July, they can compete with the California cherries that are selling for $5.99 a pound in supermarkets.

“Chances are, our local cherries would be a lot higher quality, and we could probably get $6.99, $7.99 a pound,” he said. By plugging those numbers into the spreadsheet, figuring out the yield and value per acre, you can see how long it would take you to pay for that roof.”

Lang has had visitors to the orchard to see the roof structure, and he has been fielding questions from cherry growers in California, Washington, Oregon and other parts of the world.

“There are definitely people trying to figure out if it would work for them,” he said. With the benefits of the roof in terms of harvest and pruning timing, higher quality fruit, reduction in some diseases as well as winter damage, and decreases in chemical sprays, the roof is an interesting option, Lang said. “And if you can find a high-value market, it’s possible that a retractable roof could make sense for you.”

To build a retractable roof

MSU’s automatic retractable roof house was donated by Cravo Equipment Ltd. of Brantford, Ontario. For decades, the company had been making the structures for garden centers and for use over certain crops, such as tomatoes, and reached out to MSU in 2012 about researching the potential for cherries.

“We had been doing work with cherries in high tunnels for six or seven years at that point, so they called and asked whether growing cherries under covers made sense, and then what I thought about a retractable roof that was tied into a weather station and could be programmed to open or close based on any combination of weather inputs to help optimize the orchard environment,” recalled Michigan State University horticulture expert Gregory Lang. “And I said, ‘Wow, that sounds like a great idea.’”

The MSU structure is the Cravo X-Frame model, constructed with steel rods and perimeter bracing cables, and covered with a retractable peaked roof. A linked weather station is equipped with sensors for every condition, including rain, wind, barometric pressure (which can help predict storms as well as hail), and air and soil temperature, and the grower can program the roof to operate automatically.

– by Leslie Mertz

Leave A Comment