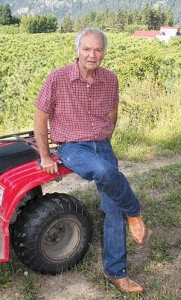

Pat Burnett tends to his 50 acres of pear orchard surrounding his red-roofed home at Leavenworth. by Geraldine Warner

Pat Burnett, who has been a fruit grower, packer, and marketer in his career—and for many years simultaneously—has always been a champion of the small grower.

Burnett was manager of the Peshastin Hi-Up fruit growing and packing cooperative in Washington’s Wenatchee Valley for close to 30 years. His goal was to take care of all the individual farmers, though he admits that not everyone appreciated it at the time.

“I was probably a tough manager,” he reflects.

When he wanted to do something at the warehouse—even something as major as adding a new building—he didn’t ask the board. He told them. “I was a strong, or bull-headed manager,” he said,

“But I never took anything to the board that I didn’t think was worth doing.”

It was a strategy that ultimately served both him and the growers well. When he retired in 2001 to focus on being a fruit grower himself, the cooperative was in enviable financial shape, with no bank debt.

Its solid financial footing has enabled the cooperative to continue to survive in an environment that has become dominated by much larger corporate packers, Burnett said. Hi-Up is one of only six remaining fruit cooperatives out of 30 or so that used to dot north central Washington.

Both sides

A good packing house manager knows both the farming and the selling sides of the business, and can empathize with the growers, Burnett says. “When you’re strictly a sales person, who are you going to look after? You have to look after the customer because that’s where your business is. If you’re a farmer as well, you’re looking at both sides of it.”

“One thing you can say about Pat is he’s a grower’s packer,” agreed Todd Fryhover, who worked for a time at Orondo Fruit Company, where Burnett became a partner when he retired from Hi-Up.

“It’s almost the polar opposite of where you’re coming from as a sales person. He really knows how to get every pack out of a bin of pears and do what’s best for the grower.

“Another strength of Pat is he’s not afraid to say what he’s thinking,” Fryhover added. “He’s not too worried about hurting people’s feelings—he just basically states the facts—but there’s no question he has the interests of the growers in mind.”

Pickers

Burnett grew up in Knoxville, Tennessee. In 1949, when he was ten years old, his parents Lloyd and Nola came to the Wenatchee Valley to pick apples for Ed Clarke at Peshastin. After a couple of years in Washington, the family returned to Tennessee.

Burnett was a high school freshman when he decided to leave school each day at noon and hitchhike eight miles into town to work in the grocery store. He had just been promoted from bag boy to shelf stocker when he was fired for being under the legal working age and hauled before the school superintendent. His family argued, successfully, for him to be allowed to keep his job.

At the age of 15, he left school and enlisted with the U.S. Army (with his mother signing the papers) but was turned in by a neighbor before he got chance to serve. As soon as he was old enough, on his seventeenth birthday, he joined the U.S. Navy and served for four years, marrying his wife JoAnn while stationed in San Diego, California.

Meanwhile, his parents moved back to the Wenatchee Valley. His uncle, who was a dentist in California, bought an orchard in Leavenworth, and his father managed it.

After leaving the Navy, Burnett joined his family and worked briefly in the Safeway store’s produce department in Wenatchee before getting a job at Peshastin Fruit Growers (now Bluebird) loading wooden fruit boxes onto rail cars going east.

He moved from there to Leavenworth Fruit, where he supervised the packing and shipping and took charge of the refrigeration. In 1972, he was hired as general manager of Peshastin Hi-Up.

It was a “bitty place,” at the time, Burnett recalls, with four or five grower members and annual production of about 60,000 boxes of fruit. The Peshastin lumber mill next door had closed and Burnett oversaw the purchase of the property, demolition of the mill, and expansion of the co-op.

He and his wife also constructed the office in the evenings. Over the years, Burnett helped the cooperative adopt new storage techniques so that the pears could be sold later in the season when prices were higher.

Since it was a small operation, he was in charge of both running the warehouse and selling the fruit. He made frequent visits to Mexico to establish relationships with buyers and hosted them when they came to Washington. When he acquired the Leavenworth orchard that had belonged to his uncle, he gained insights into the farming side of the business.

Apples

When he began working with Hi-Up, 75 percent of the fruit it handled were apples. Burnett convinced his growers that apples could be grown anywhere, but the upper Wenatchee Valley was uniquely suited for pear production.

“I haven’t seen any place that’s better. I think second best is probably Oregon,” he said with a wry smile.

Over the years, growers replaced their apple orchards with pears. Some apple orchards were removed because they didn’t withstand cold damage as well as pears, but many were removed during the late 1980s and early 1990s when growing apples was not profitable.

“I could see what was happening to the apples, and to be honest we probably have too many in the ground now,” Burnett said, noting that by the time he left Hi-Up his 40 members weren’t producing a single apple.

Today, he farms 50 acres of pears at Leavenworth that his uncle used to own, and 80 acres of pears in nearby Dryden. He also has 35 acres of cherries at Fairview Canyon near Wenatchee. A few years ago, he acquired an orchard from friend Jack Jones in Quincy, which has 170 acres of apples and 75 acres of red pears.

Fryhover said even though Burnett is now working just as a grower, he’s still very much in tune with what’s happening in the pear deal and the market opportunities.

“He can stand back and look at the whole industry, and not many people can do that anymore.”

Tony, one of Burnett’s two sons, manages the orchards and oversees the personnel, while JoAnn does the accounting and payroll. Burnett does tractor work, such as mowing and spraying, just because he enjoys it.

Housing

Besides being a great place to raise pears, the orchard offers a 360° panorama of the Cascade Mountains, which makes it prime real estate. About four years ago, Burnett almost sold the Leavenworth property (with the exception of his house and five acres around it) for $5 million.

Burnett asked for a nonrefundable deposit of $200,000 and gave the prospective buyers six months to complete the deal, which involved securing the water supply and being annexed into the City of Leavenworth. They ran out of time.

A housing development would have dramatically changed the character of the environment, but that didn’t worry him too much. There comes a time when you have to get over the sentimental attachment, he says. If it had been an apple orchard, it would be long gone.

‘“I didn’t need to sell it,” Burnett said, noting that the pears have been bringing in good revenue for the past few years. “If it wasn’t making a lot of money, it would be a different situation.”

Ironically, what’s kept the pear industry viable is a lack of research and innovation, he argues.

Orchardists are growing the same varieties they always have, and though they are planting trees closer together, the lack of a dwarfing rootstock has limited tree density. It’s kept the playing field level so small growers can remain competitive.

In contrast, apple growers who failed to keep up with a rapid shift to new varieties and intensive, early-yielding orchard systems have fallen by the wayside.

The apple industry has become dominated by large, vertically integrated companies that have the resources to keep planting and replanting and can withstand years of poor orchard returns because of their packing profits, Burnett observed.

Should a new pear variety be developed that could be grown equally well in hot areas like the Columbia Basin, with its thousands of acres of land and plentiful irrigation water, as it could in the Wenatchee Valley, the traditional growers could not compete, he said.

“What I hate to see happen is the small growers going out of business,” Burnett said.

Mr Burnett is a great man! He offered us his second floor garage and live there for a while. Both his wife and him are great people. Very please to meet them. Until now I find out how much he owns, god bless the Burnetts! Hope one day we can come by and visit him!