The increasing demand for grapevines in the Pacific Northwest has many growers turning to field grafting to expand or replace their vineyards in order to keep up with trending market demand for key varietals, but the practice comes with some significant risks.

Viruses can be spread easily between scion budwood and rootstock, which is particularly troublesome if a virus shows no symptoms.

The risks are big enough that growers should know all they can about field grafting before adopting the practice. Here we present some of the basics.

A common mistake during field grafting is mixing up scion budwood from different cultivars. This Riesling vine was grafted with scion budwood from a red grape (Cabernet Sauvignon) and a white grape cultivar (Chardonnay). In addition to varietal purity, the quality (freedom from viruses) of scion budwood is important for the success of field grafting. (Courtesy Naidu Rayapati)

What is grafting?

Grafted vines are produced by joining the fruit-bearing vinifera scion budwood to nonvinifera grapevines that will serve as the root system. Grafted vines are commonly used across many grapevine-growing regions worldwide to protect against phylloxera and nematodes. Grafted vines are also used to promote early ripening in areas of reduced heat units.

In Eastern Washington, however, wine grape cultivars are planted on their own roots, in part due to the absence of phylloxera and nematode problems.

From a grower’s perspective, a significant advantage of planting own-rooted vines is that they can be retrained from shoots emerging from buds at or below ground level, if the above ground trunk portion is killed during freezing winter seasons or damaged due to mechanical injury.

This means that growers can avoid the risk of replacing the damaged vine, in contrast to grafted vineyards where the damaged vine has to be removed in its entirety and replaced with another grafted vine.

Why top or field grafting?

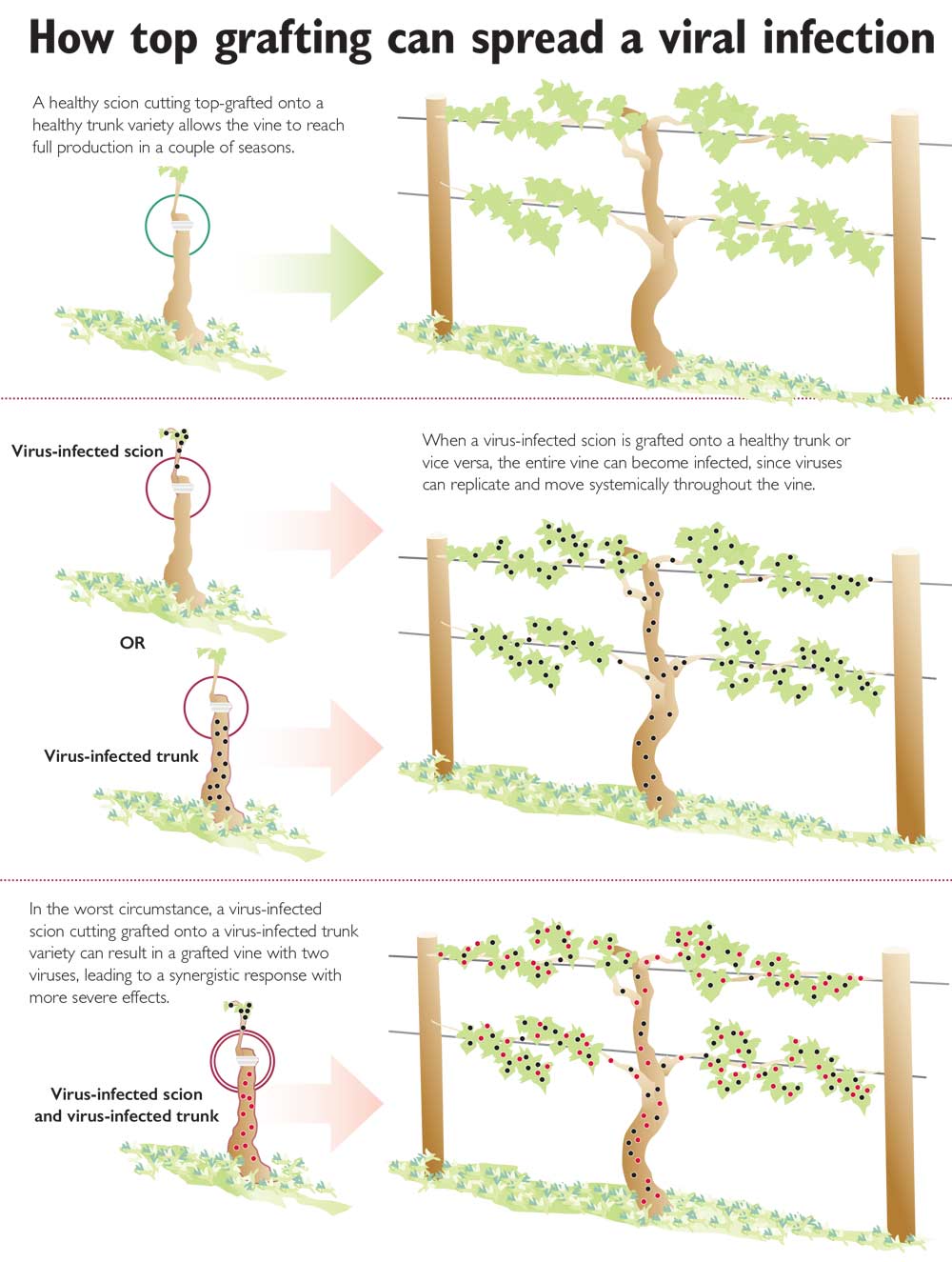

Top or field grafting involves cutting off the top of established grapevines in a vineyard and grafting each trunk with two budwood canes of a preferred wine grape cultivar. Thus, the lower trunk portion of the original grapevine acts as the established root system and the grafted budwood canes, or the scion, represents the fruiting portion of the grapevine.

If practiced properly, top grafting can be more economical than replanting the entire vineyard, because the top-grafted block can reach full production in a couple of seasons after top grafting compared to a block replanted with own-rooted cuttings that takes four to five seasons to reach full production.

What are the virus risks?

Among all factors that could influence the success of top grafting, none is more important than the sanitary status of both existing trunk vines and the scion budwood.

Viral infections are known to cause a wide range of effects on the health and productivity of grafted vines, including weakening of the grafted vine, reduced fruit yield, delayed harvest maturity and altered berry composition.

Additionally, viruses could induce graft incompatibility and enhance susceptibility to a wide range of biotic and abiotic stresses. This is because viruses are insidious and spread throughout the vine via rootstock or scion.

For example, a virus-free scion budwood grafted onto an existing virus-infected grapevine trunk would result in a virus-infected vine because the virus can multiply and spread from the trunk throughout the plant.

Likewise, field grafting with compromised scion budwood onto a virus-free grapevine trunk results in virus being spread from the scion throughout the plant. In a worst-case scenario, top grafting scion budwood infected with one virus onto a grapevine trunk having a different virus could result in a grafted vine containing two distinct viruses causing more severe symptoms and synergistic effects on vine health and fruit yield and quality.

In all of these scenarios, the virus-free status of both grapevine trunk variety and scion budwood need to be established before initiating top grafting.

Otherwise, the risk of a virus spreading in top-grafted vineyard blocks increases. And symptomatic vines not only affect vineyard productivity but serve as a “Typhoid Mary” — a source of infection leading to the increased spread of viruses within and between vineyards.

Top grafting is a relatively new strategy for Washington growers, and many of them are grafting largely red grape cultivars onto the trunks of white grape cultivars.

It is well known that white grape cultivars express no visual symptoms, whereas red grape cultivars express visual symptoms from viral infections. Consequently, the negative impacts of virus infections to vine health and fruit yield and quality could be more dramatic in white grape vineyards top grafted with red grape cultivars.

Moreover, the severity of disease symptoms may vary depending on the vinifera x vinifera combinations in a grafted vineyard and virus profile in individual grafted vines.

Top or field grafting, where budwood from a preferred wine grape cultivar is grafted onto the trunk of an established root system, saves growers time and money since the vine can reach full production much sooner than replanting. However, the method carries risks of introducing viruses that can weaken the vine and reduce fruit yield and quality. Source: Naidu Rayapati (Jared Johnson/Good Fruit Grower)

What to know

Irrespective of the cultivar, viral infections can significantly reduce the survival rate of top-grafted vines compared to vines grafted with virus-free plant material.

Since the trend for top grafting with preferred wine grape cultivars is increasing, and several growers are making contingency plans to proceed with field grafting, preventive measures should be implemented to avoid negative impacts of viruses in top-grafted vineyards.

The following are some best-practice guidelines to avoid virus problems in top-grafted vineyards:

On the surface, dormant wood from healthy and virus-infected vines look similar, so a visual inspection of a vineyard block that is to be top grafted may not give clues about the viral status of the vines. Since viruses can spread from budwood cuttings used for top grafting and/or from infected trunks of existing vines, growers have to ensure that both scion and rootstock are free from viruses to avoid the risk of spreading viruses.

That means growers should perform health assessments of all vineyard blocks to be top grafted.

Collect samples representing a cross section of a vineyard block and test them by molecular diagnostic assays to determine the viral status of vines.

Growers should test initially for Grapevine leafroll-associated virus 3 (GLRaV-3) and Grapevine red blotch virus (GRBV), the two most economically important viruses of concern for Washington vineyards, to estimate the potential risk from viral infections and to make informed decisions about whether to proceed with top-grafting.

Growers are encouraged to use scion budwood from certified nurseries or a reputable source. If growers want to use scion budwood from an existing vineyard, they should get samples tested for GLRaV-3 and GRBaV before collecting canes for grafting.

Monitor top-grafted blocks during the season to ensure that grafted vines are well established and free from viral infections. If grafted plants are showing symptoms during the season, test suspected samples for the viral status of symptomatic vines.

Similarly, growers should pay attention to gall formation at the graft union. Presence of galls at the graft union is likely due to crown gall bacterium.

Affected vines should be removed to eliminate the spread of viruses and crown gall bacterium.

The WSDA Specialty Crop Block Grant Program has funded a three-year project to analyze the impacts of virus diseases in top-grafted vineyards and to show the financial benefits of adopting knowledge-based, best-practice guidelines for establishing healthy top-grafted vineyards. •

Impacts of viruses in top-grafted vineyards

During the past two seasons, Washington State University grape virologist Naidu Rayapati observed leafroll-like symptoms in two Riesling blocks that were top grafted with budwood canes from Syrah and Cabernet Sauvignon, and in one Gewürztraminer block top grafted with budwood canes from Syrah.

Prior to top grafting, both the Riesling and Gewürztraminer blocks showed no visual symptoms, and growers assumed these blocks were “healthy” and went ahead with top grafting.

However, some vines in all of these top-grafted blocks showed symptoms during the very first season after top grafting (Fig. 1 and 2).

Figure 1: Field-grafted vines showing leafroll-like symptoms in a red grape cultivar. These Riesling vines were field grafted with scion budwood from Cabernet Sauvignon. The grafted vine on right shows leafroll-like symptoms and tested positive for leafroll (GLRaV-3). The non-symptomatic vine on left is negative for the virus. (Courtesy Naidu Rayapati)

Figure 2: Field-grafted vines showing leafroll-like symptoms in a red grape cultivar. These Riesling vines were field grafted with scion budwood from Syrah. The grafted vine on left shows severe symptoms and tested positive for grapevine red blotch-associated virus (GRBaV). The nonsymptomatic vine on right is negative for the virus. (Courtesy Naidu Rayapati)

This is because red-fruited cultivars are known to express visual symptoms on foliage due to viral infections.

Virus indexing by PCR diagnostic assays revealed the presence of GLRaV-3 in the Riesling and Gewürztraminer blocks. In a different Riesling block top-grafted with Syrah, some symptomatic vines tested positive for GRBaV, some for GLRaV-3 and others for both viruses.

Affected vines produced significantly less fruit with low amount of sugars, the hallmark of fruit quality.

Viral problems can also affect vineyards top grafted with white grape cultivars. In one Riesling block top grafted with scion budwood from Sauvignon Blanc, some grafted vines showed severe stunting and yellowing of leaves, despite the lack of dramatic symptoms seen in red grape cultivars (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Field-grafted vines showing virus-like symptoms in a white grape cultivar. These Riesling vines were field grafted with scion budwood from Sauvignon Blanc. The grafted vine on left shows severe stunting and yellowing of leaves and tested positive for GLRaV-3. The non-symptomatic vine on right is negative for the virus.(Courtesy Naidu Rayapati)

The affected vines tested positive for GLRaV-3 and a few other viruses and produced fruits with inferior quality.

At this time, it is not clear if the observed symptoms were due to viruses present in the trunk of existing white grape cultivars and/or introduced via top-grafted scion budwood, but the appearance of symptoms in these blocks is an indication that much needed attention was not paid to the sanitary status of plant material while proceeding with top grafting. •

Naidu Rayapati, Ph.D., is a grape virologist at Washington State University’s Irrigated Agriculture Research and Extension Center in Prosser, Washington. For guidance or advice to assess the sanitary status of a vineyard block prior to top-grafting or to monitor top-grafted vineyards for viral infections and crown gall, contact him at naidu.rayapati@wsu.edu or 509-786-9215.

Leave A Comment