A traditional Darwin string thinner works just fine on fruit trees trellised or hedged in flat, flowering walls.

But the trees supplying California’s canned peach industry don’t always grow that way, and few growers can afford to up and replant their entire orchard at once.

Frank Bavaro (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

So, Frank Bavaro, a mechanically handy cling peach grower in the Central Valley, rebuilt a Darwin instead.

Using the Darwin’s hydraulic motors and orbital spinning shafts, Bavaro made two modifications: He mounted the thinners horizontally on a high post to break up the clusters on the tops of trees, and mounted one vertically onto a pivoting arm that allows a worker to swing the strings in and out of the canopy to follow the contours of the branches.

He considers the modifications easy and cheap.

“Literally, for $1,000, and a guy’s got one,” said Bavaro, known by family members and friends for converting an old airplane prop into a ceiling fan, a giant mill saw blade into a patio furnace and an old grain mill into an entertainment center.

Last year, Bavaro ran his own trials on 7.5 acres of his own Ross variety trees and found that the thinner reduced his labor needs and increased fruit size.

He built three more of his homemade thinners, towed behind a conventional tractor, and used them this year on 125 acres — about 75 percent of his canned peach farm on the banks of the Stanislaus River in Escalon.

A custom built blossom thinner designed to be manipulated between peach trees is used on March 8, 2016 at Bavaro Ranches Inc., in Escalon, Calif. The device, operated by Adrian Rey, uses the flailing whips from a Darwin string thinner and is hand operated to better access the structure of a traditional vase style architecture. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

Sure enough, he said, he got more of his orchard thinned and larger fruit for a fraction of the cost, he said. Now, he wants other growers to come and steal the idea he believes will work on fresh market peaches as well as canners. He has no ambition to patent or trademark it.

“What I would really like is for people to look at this thing,” he said. “Try it. It’s a no-brainer.”

Trimming labor costs

Industry education was the idea in the first place, said Rich Hudgins, president and CEO of the California Canning Peach Association. “That was our desire from Day One,” he said.

In 2008, the Sacramento-based association teamed up with California’s peach canning companies to set aside industry funds for mechanization research to cope with a dwindling labor pool and rising labor costs. The groups raised $1.1 million in the three-year funding period.

Together, they purchased two Darwin string thinners — at roughly $10,000 each — and ran trials with a local farm adviser and growers in and around Yuba City and Modesto.

Orchardists lost interest after struggling to maneuver the spinners in and out of the vase-shaped tree canopies, so the machines were not used as much as they had hoped.

Hudgins agreed to let Bavaro take a stab at modifying one of the Darwins to work better in the existing orchards.

Isaac Bernardino operates a custom built overhead blossom thinner on March 8, 2016 in a cling peach block at Bavaro Ranches Inc., in Escalon, Calif. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

“We’re all for this,” Hudgins said. “We’re pleased we’ve got somebody out there with a little different twist on the Darwin.”

Hudgins expects more growers will adopt his method, or something similar, hoping for some labor-expense relief after the California State Legislature passed a law that will gradually increase the state’s minimum wage to $15 per hour by 2022.

“It makes it all the more the imperative that we find a way to reduce our reliance on hand labor,” Hudgins said.

The state’s industry has funded other experiments with vacuum harvesters, drum shakers, handheld string thinners and experimental plantings. Currently, the state harvests about 10 percent of its cling peaches mechanically.

The organization represents about 400 growers, roughly 80 percent of the state’s cling peach industry. The group negotiates prices with the canners on behalf of the growers. Currently, the negotiated price is $490 per ton.

About 30 to 40 percent of the state’s cling peaches are marketed to the food service industry, which includes schools, cafeterias, prisons, hospitals and senior nutrition programs.

Bavaro’s savings

In the past, Bavaro typically hired 25 employees for 30 days just to thin fruit by hand, using ladders, at a cost of $900 to $1,200 per acre.

This year, using his new invention on mostly V-shaped trees, Bavaro cut that to nine workers. Meanwhile, his fruit came out with better quality and size and required less postbloom hand thinning because it allowed for eyeball decisions from his employees about how aggressively to knock away blossoms, he said. Overall, he spent between $325 and $425 per acre.

Bavaro has plans for the future, too.

Next year, he plans to fit two swinging arms onto both sides of the thinner, each operated from a platform towed behind the tractor.

That will allow a worker on each side of the alley to thin simultaneously without making them walk, alleviating a safety concern.

He also is tinkering with a way to get a string thinner into the center of the tree, a hurdle he has yet to leap.

Like other peach growers, Bavaro is planting new blocks that he will train for shape uniformity from the beginning to make way for mechanization, such as a more traditional string thinner and maybe mechanical harvesting someday.

He has to, he said, if he wants to stay in the peach business — which he does. Workers are only going to get more scarce and expensive.

“You got to face the reality of it,” he said. •

– by Ross Courtney

By The Numbers: Bavaro’s Thinning Trials

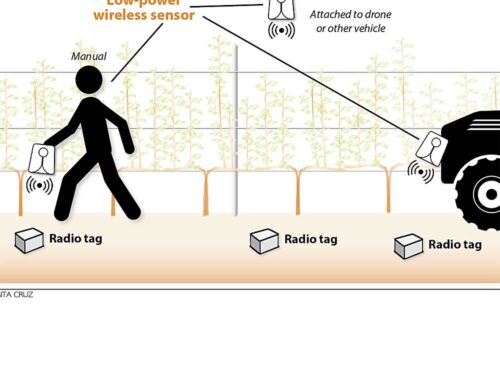

Frank Bavaro, a cling peach grower in Escalon, California, modified a Darwin string thinner to feature a pivoting arm that allows movement in and out along the contours of the orchard canopy.

He ran his own trials in 2015, comparing string thinner use at bloom four different ways, as well as traditional hand thinning at pit hardening, on a total of 500 14-year-old Ross variety V-shaped trees planted in 16-foot rows with 8-foot spacing. Each trial was 1.5 acres.

He chose Trial No. 3 to repeat commercially on about 125 acres this year and is having similar, if not better, results, he said.

—Trial 1: String thinning the sides and tops of trees and no hand thinning

Cost per acre: $140

Production per acre: 33.6 tons for canning, 7.3 tons for juice. (Canners pay a flat, negotiated price of $490 per ton of fruit that meets the minimum size of 2 3/8 inches diameter.)—Trial 2: String thinning and hand thinning with no ladders

Cost per acre: $230

Production per acre: 30.6 tons for canning, 6 tons for juice.—Trial 3: String thinning and hand thinning with a rubber-tipped pole but no ladders

Cost per acre: $293

Production per acre: 33.3 tons, all for canning.—Trial 4: String thinning and hand-thinning with ladders

Cost per acre: $760

Production per acre: 31 tons, all for canning.—Trial 5: Conventional hand thinning after pit-hardening in May with ladders and no string thinning

Cost per acre: $810

Production per acre: 29.3 tons, all for canning.Note: Fruit that had been string-thinned at bloom sized between 36 and 38 millimeters by pit-hardening in May, compared with 32 to 34 millimeter-sized fruit without string thinning.

Leave A Comment