Dr. Dave Rosenberger, professor emeritus, Cornell University, New York

As a plant pathologist who makes recommendations to tree fruit growers throughout New York and neighboring states, I am very concerned about evidence that some fungicides are exacerbating bee mortality as reported in the March 15 2014 issue of Good Fruit Grower.

I would like to make extension recommendations that will help to minimize threats to bees, but we need much better information from the bee research community before anyone can formulate management changes that will protect both the bees and our tree fruit crops.

Bee researchers and beekeepers who suggest that growers should simply avoid spraying fungicides during bloom when bees are foraging display an extreme naiveté about crop protection.

In nonarid environments, most fruit growers will apply fungicides during bloom in most years because failure to do so could create an outcome just as disastrous has having no bees: the entire crop could be lost to fungal diseases.

Fungicide applications during bloom cannot always be made at night (to avoid foraging bees) due to constraints of weather and acreage to be covered.

Thus, fruit growers need to apply fungicides during bloom just as much as beekeepers need to introduce pesticides into their hives to control Varroa mites.

Which fungicides?

Rather than blaming fungicides as a category and then suggesting that all fungicides be avoided during bloom, we need to know exactly which fungicides contribute to bee problems and at what application timings.

By my count, we currently have at least 25 active ingredients labeled for use as fungicides for apples during bloom, and there probably is about the same number available for stone fruits. However, the recent article in Good Fruit Grower mentions only chlorothalonil, a fungicide that is widely used on stone fruit but that is not labeled on apples.

I am aware that other lab-based research has suggested that fenbuconazole (Indar) may also interact synergistically with insecticides to harm bees. If current evidence (which is still quite limited) implicates only two from among more than 25 fungicide ingredients, then there is no basis at all for the generalization that growers should avoid all fungicides during bloom so as to protect bees. More specificity is required!

It would certainly be possible to avoid Indar (and perhaps all of the related DMI fungicides) on apples during bloom if field studies eventually prove that any of these fungicides have a negative impact on bees.

However, avoiding bloom-time sprays of chlorothalonil on stone fruits may be more difficult, at least in nonarid growing regions, because chlorothalonil is a key component of fungicide resistance management strategies for some stone fruit programs.

Ultimately, if U.S. Environmental Protection Agency scientists agree that chlorothalonil can synergize with insecticides and contribute to bee mortality, the next step would presumably involve a careful analysis of whether it will be more feasible for beekeepers to find alternative methods for controlling Varroa mite or for stone fruit growers to find an alternative for controlling fungal diseases that attack stone fruits during bloom. As Dr. Phillip Brannen, tree fruit pathologist in Georgia, suggested in an e-mail exchange on this subject, “This is why God made the EPA.”

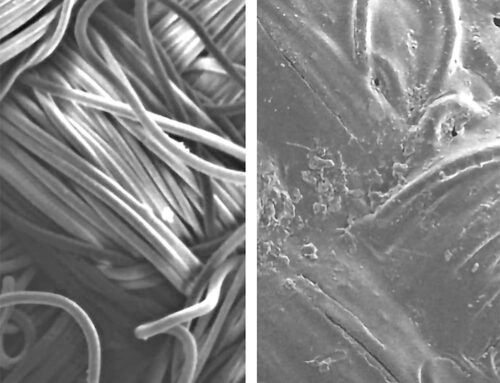

Ground cover

A case could be made for eliminating flowering weeds from orchard ground cover. (Geraldine Warner/Good Fruit Grower)

Finally, if there is a real concern that fungicides can synergize insecticide toxicity to bees, then we may need to consider impacts of pesticide combinations that are applied before and after bloom as well as those applied when trees are in bloom.

There is increasing recognition that wild honeybees and other native pollinators can play a significant role in orchards, especially in eastern United States where smaller orchards are surrounded by unfarmed habitat.

However, the ground cover in most eastern orchards contains broadleaved weeds (e.g., dandelion, white clover) that bloom both before and after the orchard trees are in bloom. The impact of pesticides on wild pollinators that visit flowering weeds in the orchards has received scant consideration but could be important for the health of wild pollinators.

Furthermore, controlling broadleaved weeds in the orchard ground cover has positive impacts unrelated to the health of wild pollinators.

We already know that broadleaved weeds support populations of rosy apple aphid and tarnished plant bug in apple orchards and of cat-facing insects and tomato ringspot virus in stone fruits. Interest in protecting wild pollinators from pesticide exposure provides just one more reason for eliminating flowering weeds in orchard ground cover.

Ultimately, we should all realize that we live and produce food in a very complex, highly interconnected environment.

As we gradually increase our understanding of that complexity, we may need to change older and previously accepted ways of managing our crops. But precisely because of that complexity, we should reject calls for drastic changes, such as “avoiding fungicides during bloom,” until both the need for and impacts of those changes have been fully assessed. •

Learn about Dr. Rosenberger’s background and research focus at https://pppmb.cals.cornell.edu/people/dave-rosenberger.

Leave A Comment