From the tree’s perspective, the reason many Pacific Northwest Bing cherries were small this past season is simple: overset.

“There were too many fruit on every tree, so fruit quality suffers, prices drop and small sizes are unmarketable so people have terrible returns,” said Washington State University horticulture professor Matt Whiting. “It was really an exceptionally good year for flower longevity, pollination and fruit set.”

The good weather for flowers was bad news for growers who have few practical tools to deal with overset once it’s apparent. Unlike apples, for which growers benefit from decades of research into crop load control, it’s a relatively new issue for cherry growers. Before the adoption of precocious rootstocks, growers could rely on pruning alone to control crop load, Whiting said.

“Now, with high-density plantings and precocious, dwarfing rootstocks, the potential to overcrop is real and perennial,” Whiting said. “So we need to revisit the issue of crop load management for sure.”

At the Washington State Tree Fruit Association Annual Meeting, he plans to give a talk on “15 months of crop load management” that is expected to draw significant interest following a tough season.

The fundamental challenge is that fruit set in cherries is much more variable than apples, due to sensitivity to environmental conditions. Early Robin orchards that produced 3 to 5 tons per acre last year saw 10 to 12 tons per acre this year, Whiting said. Managing in the face of that much variability is difficult, but growers can miss their best opportunities to control crop load if they wait to see how big the bloom or fruit set ends up.

“Your cheapest crop load management technique starts with your pruning, if you come to the spring and you see there are too many cherries on your tree, everything becomes more expensive,” said Lynn Long, semi-retired extension horticulturist with Oregon State University in The Dalles.

“I really think that we often miss our first opportunity to control crop load. Too often I see growers chasing a crop. One year, there is too much bloom and the cherries are small, so the next year after that, they go and prune really hard, and then they have a light set, because they pruned too hard,” he said. “They respond to last year’s crop rather than looking forward to the coming crop, and I think that’s a mistake.”

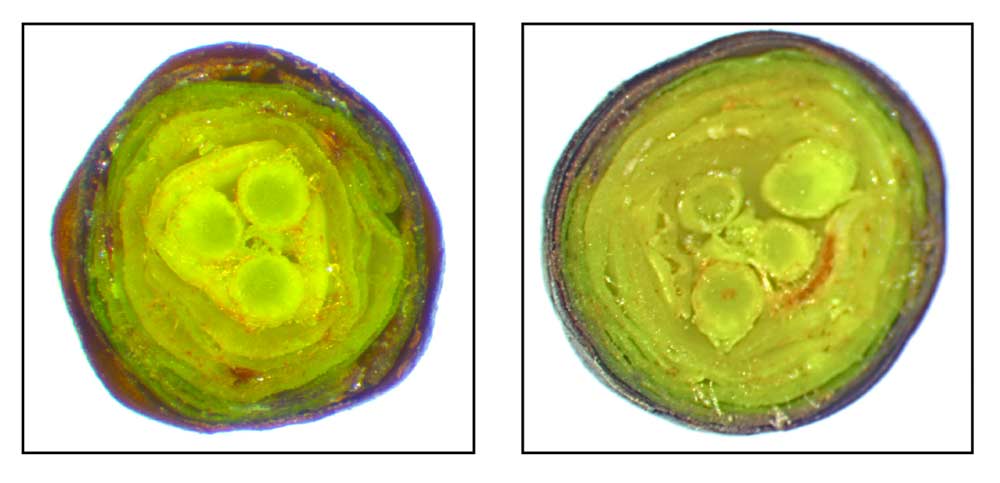

Instead of basing pruning on the past season’s fruit set, Long recommends assessing the upcoming season by cutting dormant flower buds to see how many flowers are developing. It takes some time, but doing it in every block will help growers prune smarter.

(Courtesy Lynn Long)

“Even in January, you can see the flower primordia and make an informed decision about how heavy you need to be pruning that particular block,” he said.

Last winter, the unusually heavy snows in much of the Northwest meant less time and access to pruning for some growers, which could have contributed to the overset issue as well. “My guess is that people were not aggressive enough on pruning during the off-season,” Whiting said.

Chemical tools for cherry crop load control are yet to be adopted by the industry and more research is needed to find effective tools for growers, Long and Whiting said. Chemical thinning can be done during bloom, with products such as fish oil, lime sulfur or ammonium thiosulfate proving effective during research trials. But, since fruit set is unpredictable, it’s hard for growers to look at an orchard at 50 percent bloom and feel confident making a decision to use a chemical bloom thinner, Whiting said.

The plant growth regulator Gibberellic acid can be used to reduce flower bud density in the fall if the tree appears to be setting up too many buds for the next season, but that “only works if you know you are reliably going to overset every year, and that’s not the case,” Whiting said. The potential for frost damage and other seasonal variation make this sort of advance control too risky for most growers.

So, his research has turned to post-bloom thinners, to see which apple products might have potential applications in cherries. Ethephon, a synthetic ethylene which is used to loosen processing cherries for harvest and as a rescue thinner in apples, showed the most promising results. However, in the initial study, thinning with ethephon didn’t always lead to the improved fruit quality results expected from lowering the crop load. Whiting said he’s seeking research funding to continue studying ethephon on several different cultivars and to figure out how best to use it.

Without a reliable, sprayable thinner, some growers choose to hand-thin or use a cherry rake to pull excess fruit off the tree. That work is labor intensive and expensive, but those who do it say the quality benefits are worthwhile. Long said that he knows a grower in Spain who relies on precise bud counts and will use hand-thinning of spurs to fine-tune his crop load. It’s expensive, but for that grower, it’s an investment in quality that results in premium prices.

“We know that with cherry fruit size, you can have a beneficial effect even a matter of three to four weeks before harvest,” Whiting said. “The earlier that you intervene and balance the crop load, the better, but earlier on, the risk factor is greater. Was there frost damage? Are we going to get natural drop? It causes folks to hesitate.”

Even in the face of those risks, Long urged growers to act on crop load sooner rather than later.

“The earlier, the better response from the tree and the more likely you are to have the tree respond by growing larger fruit,” he said. “This is cherries; you are already signed on to grow a risky crop, which means you will have to make decisions without all the information you need to make those decisions.” •

—by Kate Prengaman

[/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]Results are mixed after a record cherry season

Northwest cherry growers produced a record crop this season, but they’ll be looking for ways in the offseason to improve fruit size and quality next year following complaints that some of the fruit didn’t meet the industry’s usual high standards.

Beyond the obvious cause — overset trees with too many cherries — growers and shippers are scratching their heads to nail down all of the factors that led to so much small fruit that lacked sugar and firmness in Washington, the region’s biggest player. The problems varied by growing region and variety. More examination is expected into the roles high temperatures, nutrition and horticultural practices, such as lack of pruning or thinning or picking fruit too early, either as a pre-emptive move to avoid a heat wave or to hit a high market and get a better price, may have played.

The 2017 crop came in at nearly 27 million 20-pound boxes, surpassing the 2014 record of 23.2 million boxes.

However, the season got a late start, with the first shipments not being sent until about June 10, after which the “floodgates opened,” said B.J. Thurlby, president of Yakima, Washington-based Northwest Cherry Growers. Within a week, the industry was shipping 500,000 boxes a day and sustained that pace for 42 straight days.

“We’ve never seen that quick of a ramp-up before,” Thurlby said. “That tells me we can move a lot of fruit when we need to, but the markets, when they received the fruit, didn’t move it as quickly as we needed.”

And right after the July 4 holiday, the law of supply and demand kicked in — and demand wasn’t what it’s been in the past. The “super-consumers,” those who buy cherries 10 times a season, just didn’t buy as many times last season, he said.

“The key is that we have to have fruit that really inspires people to come back and keep buying,” he said. “Some of this year’s fruit didn’t.”

Advertising and promotion activity by Northwest Cherry Growers was the highest it’s ever been, and the industry saw record shipments to almost all export markets, more than 8 million boxes, which means there was fruit that met export standards.

One area of consideration in the future: a Brix standard for dark red sweet cherries, as has already been set for Rainiers. Members of the Washington Sweet Cherry Marketing Committee will meet Dec. 14 to discuss the topic, but how likely it would be going forward is unclear.

Some early varieties have lower sugar, while others lack titratable acidity, so a Brix standard might almost have to be variety specific.

This season, in particular, Bings failed to have their usual firmness and flavor, so much so that some retailers commented on how outstanding Chelans, the first cherry picked, were this year, Thurlby said.

“At the end of the day, our production conditions were less than optimal, and I think every grower would agree with that,” he said. When growers can export to Korea on 10-row fruit, which averages $47 per box, they have to focus their efforts on getting that quality of fruit, “and then we need to sell that fruit on the domestic market as well.” •

– by Shannon Dininny

Leave A Comment