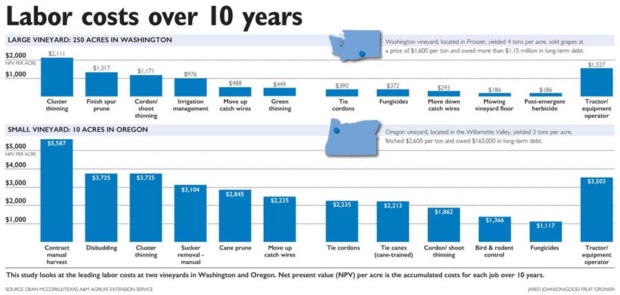

CLICK TO ENLARGE — This study looks at the leading labor costs at two vineyards in Washington and Oregon. Net present value (NPV) per acre is the accumulated costs for each job over 10 years. Source: Dean McCorkle/Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service (Jared Johnson/Good Fruit Grower illustration)

Wine grape growers looking to mechanize in Washington may want to eye cluster thinning, the most expensive chore in terms of labor. In Oregon, contracted manual harvesting tops the list.

Those are among the preliminary conclusions of Dr. Dean McCorkle, a Texas A&M University economist examining the facets of wine grape growing that might be ripest for automation.

McCorkle, an extension specialist with the university’s Agriculture Economics Department in College Station, Texas, is leading a team of economists and engineers in a three-year project to find ways to mechanize wine grape vineyards.

The first step, he figured, would be to calculate the cost of labor for different tasks and maybe give engineers an idea of where to target their innovation, identify the tasks that lend themselves to mechanization and determine technical requirements.

“A lot of this is going to be some work the engineers do,” McCorkle said in an interview with Good Fruit Grower.

For example, cluster thinning in Washington costs an average of $238 per acre, or $527,666 for a 250-acre vineyard over 10 years, taking into account shifting prices of labor and other variables.

In Oregon, where work is done by hand on smaller properties, contracted manual harvesting costs $630 per acre or $55,871 over 10 years for a 10-acre vineyard.

If growers want to mechanize either of those duties, they would need to compare the capital expense of machinery to those 10-year costs, assuming that the new technology has a 10-year life span, McCorkle said.

McCorkle is mostly done with the math for the $462,000 research project, funded by a grant from U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Agriculture and Food Research Initiative’s Agricultural Economics and Rural Communities Program.

He shared the preliminary results with growers in January at the Precision Farming Expo in Pasco, Washington.

Engineers will work the next two years to determine which of those high-cost chores might benefit from mechanization and other details, such as how many thinning machines a 250-acre orchard might need.

Collaborating on the project are officers with RE2 Robotics, a firm in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, as well as other faculty from the Texas A&M AgriLife Extension service.

To figure out the math, McCorkle and his team assembled panels of between four to six wine grape vineyard owners and managers from each of five states — Washington, Oregon, California, New York and Texas. He also studied one panel each of table grape growers and raisin growers, both from California.

He crunched a slew of financial data, such as acreage, debt, operating budgets, price per ton, average yields, insurance coverage and more, to create a representative “typical” sample for each area.

The Washington vineyard, located in Prosser, yielded 4 tons per acre, sold grapes at a price of $1,600 per ton and owed more than $1.15 million in long-term debt, for example. The Oregon vineyard, located in the Willamette Valley, yielded 3 tons per acre, fetched $2,600 per ton and owed $165,000 in long-term debt.

Using economic models, he projected 10 years into the future how well the ledgers of each vineyard might fare with current equipment and technology, asking if each was economically viable.

“For Washington, I would say yes, over the next 10 years,” he said in an interview. “For Oregon, I wouldn’t say that.” Oregon wineries are most likely tied to an estate winery that profited, something his calculations did not factor, he said.

He also averaged the cost of labor for different tasks around the vineyard, such as canopy management, pest control and harvest.

In total, the Washington growers spend just shy of $1,000 per acre on labor for those chores, while Oregon growers spend nearly four times that, again, because they use more hand labor.

Broken down, cluster thinning, finish spur pruning and cordon shoot thinning were the three most expensive jobs in the Washington vineyard. Contract manual harvesting, disbudding and cluster thinning were the top three at the Oregon vineyard.

In Texas, McCorkle’s team used data from two representative vineyards. In the 50-acre operation, finish spur pruning, shoot positioning and hoeing were the top three chores. In the 100-acre vineyard, finish spur pruning, shoot positioning and raking brush topped the list.

New York’s top three were cane pruning, contract manual harvesting and tying cordons for a 50-acre representative vineyard. Statistics for California, on a 30-acre vineyard, were not complete. •

– by Ross Courtney

Good article! There is already equipment available for mechanization of shoot/cluster thinning, sucker removal, wire lifting, finish spur pruning and leaf removal. Just trying to figure out when it becomes economically feasable is the question now or if labor is available.