U.S. Department of Agriculture scientists have developed a chemical lure for the spotted wing drosophila that is more effective, consistent, and longer lasting than standard food baits and makes traps easier to service.

Growers have been using wine and/or vinegar in traps to monitor the insect. The flies are attracted by the odor, drown in the liquid, and can then be identified and counted.

A drawback of this approach is that the volatiles in wine and vinegar quickly dissipate, so that the trap soon loses its attractiveness and is not consistently attractive over time.

Another problem is that the wine and vinegar attracts many other insects, so that identifying spotted wing drosophila (Drosophila suzukii) in the liquid can be tedious and messy.

The fly is only 2.0 to 3.5 millimeters long—the same size as its close relative, the common vinegar fly (Drosophila melanogaster).

Merlot

SOURCE: Peter Landolt, USDA-ARS

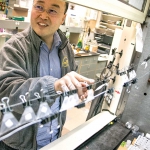

In an effort to design a better fly trap, Dr. Peter Landolt and Dr. Dong Cha at the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s laboratory in Yakima, Washington, set out to identify the specific components of wine and vinegar that the spotted wing drosophila found most attractive.

Landolt, research leader at the lab and an expert on insect attractants, had already done research showing that spotted wing drosophila flies preferred Merlot to other wine varieties, that they preferred rice vinegar over other types of vinegar, and strongly preferred a mixture of the two materials.

It is thought that the insect is actually looking for a source of sugar, but since sugar is not volatile (has no smell), it orients to the strong smell of fermented fruit products that are rich in sugars. It may be attracted to the yeast that ferments the fruit, which is also a part of its diet.

Insects detect odors with receptors on their antennae. For the experiments, Landolt and Cha mounted a tiny electrode either against the neural lobes on the back of the severed head of a spotted wing drosophila or on a freshly plucked antenna so that electrical signals from the receptors could be recorded and magnified as they detected volatile chemicals in wine and vinegar.

At the same time, they used gas chromatography and mass spectroscopy to identify the chemical components in the wine and vinegar that elicited responses from the antenna.

After being detached from the body of the insect, an antenna remains responsive for about a day, Cha told Good Fruit Grower.

During a series of such experiments, fly antennae detected 13 chemical components of the very complex bouquet of wine and vinegar.

The next step was to expose live flies to those chemicals in lab assays to find out which chemicals attracted the flies and which repelled them.

Combinations of the attractive chemicals were then tested in traps in the field and compared with a wine-and-vinegar bait.

The scientists found that the most attractive chemicals were acetoin and methionol, combined with pure ethanol and acetic acid.

The next step was to develop a dispenser that would release the four chemicals consistently in a trap over a long period of time. If a grower wants to interpret trap catches, the attractiveness of the trap must be stable, Landolt said.

In field trials in Washington, Oregon, and Mississippi with cherries, blueberries, blackberries, and raspberries, the new four-component lure never failed to catch large numbers of flies, Landolt reported.

It was used in a dome-style trap with a large bottom entrance, which Landolt believes is more effective than traps where insects enter through funnels or holes in the top or sides.

The lure was effective early in the season, when fly populations are low, as well as later in the season when ripening fruit competes for the fly’s attention.

Landolt said he and Cha moved well beyond the initial goal of trying to come up with chemicals that would be as attractive as wine and vinegar. By altering the amounts and ratios of the chemicals, they roughly doubled the attractiveness of the lure.

“Now, we’re quite a bit better than wine and vinegar consistently,” he said.

Other insects

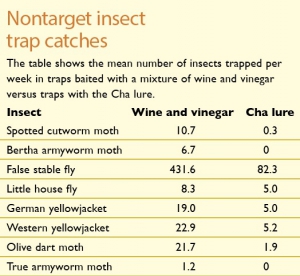

Another advantage of the new chemical lure is that it attracts far fewer nontarget insects. In traps with wine and vinegar or other food baits, the liquid can be completely filled up with insects of many kinds, and most of those are not spotted wing drosophila flies.

In contrast, where the new lure is used, the drowning liquid is usually clear, with primarily spotted wing drosophila and just a few other insects in it, Landolt said. In field tests, the new lure attracted far fewer noctuid moths, muscoid flies, yellowjackets, and other drosophila species than the wine and vinegar (see table above).

“It’s not absolute, but the difference is very great,” Landolt said.

Landolt and Cha are now finalizing work to determine the optimal release rates for each of the four chemicals.

Trécé has a new lure called the Pherocon SWD Dual-Lure on the market this season that uses the four chemicals and can be used with apple cider vinegar or a neutral drowning solution, such as water with antifreeze or soapy water (see “SWD bugs California growers”).

The controlled release lure lasts for up to 30 days. Scentry is developing a version of the lure called V2.

Landolt expects the Cha lure will be useful to growers not only for monitoring the arrival of the pest in an orchard, but for assessing how well treatments have controlled the insect.

He’ll be working with other entomologists to figure out how the lure can be useful in integrated pest management programs. •

Leave A Comment