Researchers, with the help of electron scanning microscopes, can view cherry reproductive organs, like this stigma of a Sweetheart cherry.

Photo courtesy of Matt Whiting, WSU

Pollination and fruit set in sweet cherries play such big roles in yield and fruit quality, yet both are unpredictable and vary dramatically from year to year. Washington State University researchers are working to better understand why some varieties struggle to achieve adequate fruit set in hopes of giving growers tools toward more consistent production of high-quality fruit.

The number of fruit per tree varies dramatically from year to year, and has a great impact on fruit quality, said Dr. Matthew Whiting, WSU horticulturist. Whiting and other Pacific Northwest scientists have studied pollination, germination, and fruit set in recent years, and while they don’t have all the answers, they are beginning to learn why some cultivars seem to have higher fruit set than others.

Environmental scanning electron microscopy allows scientists to greatly magnify reproductive organs of flowers and study pollen germination, pollen growth, ovule longevity, and stigma receptivity. Whiting’s research combines field studies with growth chamber studies, and he is focusing on four varieties. Bing represents a highly productive, self-sterile variety, while Regina is self-sterile but not productive. Self-fertile varieties being studied are Sweetheart (high productivity) and Benton (low productivity).

Germination

“We’re trying to understand the maternal and paternal issues and the role that pollen germination has,” Whiting said. In one field study, where they hand-pollinated numerous varieties to follow pollen germination and fruit set, they found wide-ranging results.

For example, when pollen from the New York selection NY 54 was hand applied to Lapins blossoms, four out of every five flowers turned into fruit. But the same hand pollination of Regina with NY 54 pollen only resulted in just over one of every ten developing into fruit.

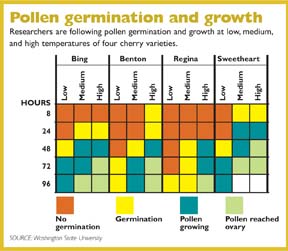

In tracking how quickly pollen germinates, Whiting said they observed no pollen germination at 24 hours in Benton, but in Bing, pollen starts germinating within 8 hours and is in full germination at 24 hours.

Temperature has a great effect on germination and growth, with low temperatures reducing germination and growth. However, highly productive varieties show faster germination and growth, even under low temperatures, than the less productive varieties.

Additionally, ovules stayed alive longer in the highly productive varieties than in the unproductive cultivars.

To find how temperatures and wind affect fruit set, Whiting compared fruit set in blossoms exposed to four treatments: ambient air, a blower device blowing ambient air, a device blowing cooled air, and a blower with heated air. Fruit set was highest (75 percent) in the ambient treatment, but dropped to about 45 percent in the blower treatment with ambient air. Fruit set was lowest in the blower treatment with heated air (30 percent). “That shows that just a little velocity of wind can reduce fruit set,” he said.

Plant growth regulators

Whiting is also testing a host of plant growth regulators, including cytokinins, gibberellins, and auxins, to see if fruit set in unproductive varieties can be improved. Thus far, he has seen the most success in improving fruit set with the synthetic auxin 4-chlorophenoxyacetic acid (CPA), as well as Retain (aminoethoxyvinylglycine), with which he made two applications at bloom (10 percent bloom and 50 percent bloom). He stressed that the plant growth regulator work is preliminary, and many of the products, like Retain, are registered for other crops like apples, but not for sweet cherries.

In working to better understand fruit variability, WSU and Oregon State University researchers are looking at various factors that could influence size and quality, including time of flowering and position on the tree. Technicians have tagged individual flowers and tracked fruit development to learn if fruit location makes a difference.

Three-dimensional mapping of individual fruit on the tree is also being done, plotting each fruit and collecting data as the fruit grow. Thus far, Whiting said that they have not found clear positional trends in terms of where fruit are located (base of shoot or further out to the shoot tip), and data has been inconsistent in terms of flower timing and fruit quality.

Eventually, Whiting hopes to develop a model that would be based on temperature and environmental factors needed for successful fruit set in different varieties. Such a model could help growers understand what leads to strong fruit set.

Whiting shared his research results during the Cherry Institute meeting held in early winter in Yakima, Washington.

Leave A Comment