Funding for nutrition programs appear to be the chief sticking point.

Farmers might well ask, “What evolution?” Action to pass a new farm bill has been stalled in Congress since last July, the 2008 Farm Bill expired in September, and there was considerable doubt whether action would take place during the postelection lame duck session. The new bill may pass during December, or the old bill may be extended, or chaos may be the order of the day as farm law reverts to “permanent legislation” of 1949 when 2013 dawns.

Those who worked to write a new 2012 Farm Bill were pressing their fellows in Congress to pass it. Should it not pass, the effort expended this year will go for naught, and it would be back to square one in 2013.

Schweikhardt spoke to fruit and vegetable growers during the Great Lakes Fruit, Vegetable, and Farm Market Expo in early December. Many of them were wondering what had stopped what seemed to be an uneventful march to a new farm law that would pass well before the old law expired last September 30. Schweikhardt, an agricultural economist at Michigan State University, explained it this way.

The “grand bargain” struck in 1973 has fallen apart, he said. That year, farm state legislators in the U.S. House of Representatives realized they did not have enough votes to pass a new farm bill with the price supports and direct income payments to farmers—and they needed to find new friends.

“Every farm bill involves a search for a new constituency, a coalition that can pass a farm bill,” Schweikhardt said. To get those 218 votes in 1973, “a grand bargain was struck and food stamps became part of the farm bill for the first time. There were only about 75 ‘pure farm’ districts then, and there are probably fewer than that now, so farm state legislators needed to find something that would win votes from urban legislators.”

In 1973, that coalition formed around supplemental food aid for poor people.

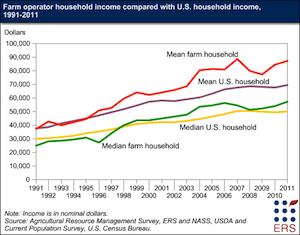

In the years before, farm bills had been passed based on the perception that farmers were poor people and needed income support. By 2000, Schweikhardt said, average household incomes on farms had exceeded nonfarm household incomes, and since then, given high commodity prices, the gap has steadily widened.

“It is very hard to justify taxing lower-income people to pay those with higher incomes,” he said.

Over recent years, new constituents have joined on in support of the farm bill, which historically has been nonpartisan on a political party level. In the 1980s, environmentalists were wooed with conservation provisions.

Direct payments

In 2008, Sen. Debbie Stabenow, the Michigan Democrat who now chairs the Senate Agriculture Committee, brought new constituents on board by her work to develop the new Title X horticulture provisions. That brought support from those concerned about obesity and health issues and led to funding for research and marketing to growers of specialty crops—fruits and vegetables.

But the 2008 law did not end support for sugar, corn, cotton, rice, and other commodity crops.

In forming this new farm bill, Stabenow and the Senate Ag Committee realized support for price supports was waning. And at that time, all committees were being told by leadership to cut the size of the federal budget. Congress had passed the Budget Control Act, which was supposed to cut $1.3 trillion from the federal budget. It created what is now called the “fiscal cliff,” but at the time was supposed to provide incentive to cut spending. It provided the perfect rationale to end direct payments to farmers.

“Direct payments are off the table,” Schweikhardt said. “What’s the justification for paying corn farmers 28 cents a bushel on their historic corn base, no matter what the price of corn is or even whether they now grow corn?”

Public perception is that government pays farmers not to farm—something that originated in the 1930s when farmers killed piglets and dumped milk to improve prices. But today, government programs, except for diverting some acres to conservation purposes, don’t pay farmers not to farm. Government programs pay farmers a premium to farm.

The Senate Ag Committee proposed a new law that would eliminate direct payments and cut costs by $23 billion over the five-year life of the bill.

Food stamps

But there was one other sticking point.

“Waste, fraud, and abuse” in the food stamp program—which was providing benefits to college students, lottery winners, and others who had income enough to buy food—was causing adverse public reaction and led Stabenow’s committee to cut $4 billion (over five years) from SNAP benefits.

SNAP is the modern name for food stamps, standing for Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, and in 2011, it provided benefits to about 46 million Americans. The number has risen by 19 million since the recession began in 2007. In 2011, the federal government spent $76 billion on SNAP benefits.

The bill developed by Senate Ag Committee passed the full Senate and was sent to the Agriculture Committee in the Republican-controlled U.S. House of Representatives. That committee decided to cut SNAP benefits even more, by $16 billion. But the bill that passed the committee was not brought to the House floor for a vote. House leaders decided, even with the cuts, there were not enough votes to get the bill past the Tea Party wing of the Republican Party.

Since the 2008 Farm Bill expired last fall, some programs have lost their authorization and funding. No new contracts can be signed under the Conservation Reserve Program or the Market Access Program that specialty crops growers use to build markets for exports.

The bill now stalled in the U.S. House of Representatives would have increased funding for specialty crops block grants and some other programs. “Fruits, vegetables, and specialty crops are ‘held harmless’ or get small funding gains in both the House and Senate versions” awaiting final action in the House, Schweikhardt said.

The two bills, named in the Senate as the Agriculture Reform, Food, and Jobs Act of 2012, are “comparable in most respects,” he said, and a conference committee could move quite quickly to resolve differences if the House would pass the bill.

In early December, it was not yet clear whether farm law would also take a plunge off the fiscal cliff.

Leave A Comment