It’s been 20 years since northeastern U.S. fruit growers—from the Midwest across the Great Lakes region—last experienced a “test winter,” where low temperatures and deep snow tested trees’ and vines’ ability to withstand tough winters.

Since 1994, the variety mix has changed in most fruits, but grapes have seen bigger changes. Perhaps enticed by the decidedly warmer winters coming with climate change, wine grape growers have been planting vinifera cultivars where once they planted hybrids (see “Vinifera grapes hit hard”).

Growers and their advisors are still assessing the damage to fruit trees from midwinter low temperatures around -20˚F and near-record snow depths. Much of the damage was physical.

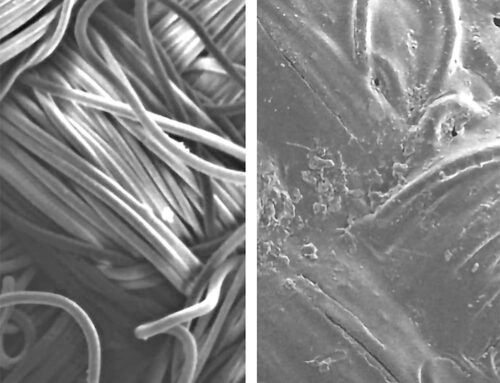

Deep snow covered tree trunks and lower limbs for long periods, allowing rodents to feed unseen beneath the snow on tree bark and limbs.

On young trees, lower scaffold limbs broke off at the trunk from the sheer weight of the snow. The deep snow allowed rabbit feeding, also injuring many limbs higher in the tree.

Many growers in Michigan lost trees; a bridge-grafting demonstration was held in April on Fruit Ridge north of Grand Rapids, Michigan, where growers had seen the deepest snow level—about 115 inches—since 1952.

Growers at the workshop learned how to save trees that had lost a third of their bark and were advised to forget about those with girdling greater than that.

Mark Longstroth, the Michigan State University tree fruit educator in Van Buren County, the heart of southwest Michigan’s fruit belt, is a keen observer of weather-related fruit issues.

“I scout all day Monday each week looking at fruit plantings, then I meet with growers about five o’clock to listen to what they say they’ve seen,” he said.

That’s followed by a conference call on Tuesday with the tree fruit educators in four Michigan regions. After the call, Longstroth writes a report for the MSU fruit website.

What cold kills

Van Buren County is normally part of Michigan’s “banana belt,” having the mildest winters with good snow cover protecting fruit trees and bushes. This year, however, temperatures inland from Lake Michigan fell four times to about -20˚F, Longstroth said.

Temperatures that low will kill peach tree flower buds, test Japanese plum varieties, and kill wood on peaches, wine grapes, and blueberries.

Longstroth has a 12-16 rule for peaches. Minus 12 will kill 10 percent of the flower buds, and -16 will kill most of them. “In Indiana, the rule of thumb is you lose 10 percent of the buds for every degree below minus 10,” he said.

“We thought we’d see which varieties do well and which don’t,” Longstroth said about the aftereffects of winter. “But instead we saw that the winter was cold enough to hurt anything that was weak. We’re seeing more injury in older apple trees than in young ones. We are seeing real differences in sites.

The closer you were to Lake Michigan, the better off you were. The further you get from the lake the more damage you see. Sites with good air drainage generally fared much better than those where cold air collected. On good sites close to Lake Michigan, they have a crop of peaches, and away from the lake, they are wondering what portion of their trees will survive.

“We are even seeing some apple trees collapsing,” he said. “Indiana reports the same. Older Mutsu, Rome, and Jonagold trees are looking poor in some orchard sites, with scaffold limb dieback and brown cambium tissue. This damage is more common on trees on sandy knolls and in frost pockets.”

Some trees on Malling 9 rootstocks are going down, especially if they were drought-stressed or overcropped last year, he said. Some of the damage is attributed to rapid drops in temperature to near zero in early December, which followed temperatures in the 50s the previous week.

Temperatures were around freezing after Christmas and then dropped to -20 (in the low sites) or -13 (at the good sites) on January 2 and again on January 8. After that, it stayed cold into March, dropping to -20 degrees every couple weeks, though most of the damage was probably done in the first week of January.

Michigan had a record apple crop in 2013, when trees set heavily after the freeze of 2012 that cut the state’s apple harvest to about 10 percent of a normal crop. This may have stressed trees enough to predispose them to winter injury.

Longstroth came on board as the tree fruit educator in southwest Michigan in 1994 and was greeted by one of the worst winters on record. From the start, he wrote his observations in a notebook.

“This year was like 1994, probably worse,” he said. “What we saw then was that peaches leafed out normally, but then the older leaves turned yellow and fell, and older trees declined and later died. In plums—and in some sweet cherries, too—we saw some trunk splitting and a gradual decline in tree health for several years after that.”

Injury slow to show

Winter injury is widespread in less cold-hardy fruits and ornamentals, which would be damaged by winter temperatures below -10˚F. Injury is easy to see in peaches and grapes where initial growth was nonexistent or poor.

Other types of injury are more localized to specific sites. In peaches, cherries, blueberries, and several ornamentals, there has been dieback of the shoot tips and fruit buds that failed to develop or showed some initial swelling and then stopped.

More -serious types of injury are more spotty and typically found in habitually colder sites or sites that had heavy crops last year or stressed the plants, Longstroth reported.

Other stresses that impact a plant’s ability to withstand winter cold include lack of irrigation and drought stress in 2013 or too much irrigation or fertilization in 2013, resulting in late growth that did not acclimate well going into winter, he said.

“We are continuing to see tree decline in older peach orchards in areas subjected to extreme low temperatures. Cuts made in pruning young trees with no crop reveal extensive damage to the wood in the trunk.

These trees will begin to show real stress when they leaf out, and hot, dry weather puts a real stress on the water-conducting ability of damaged wood. Leaf yellowing and wilting will be symptoms of winter injury that will become more apparent as the season progresses.”

Leave A Comment