As Brandon Hopkins pried open the abdomen of a queen honey bee, a small crowd gathered to watch as his small-scale handiwork played large on a newly donated monitor above his head.

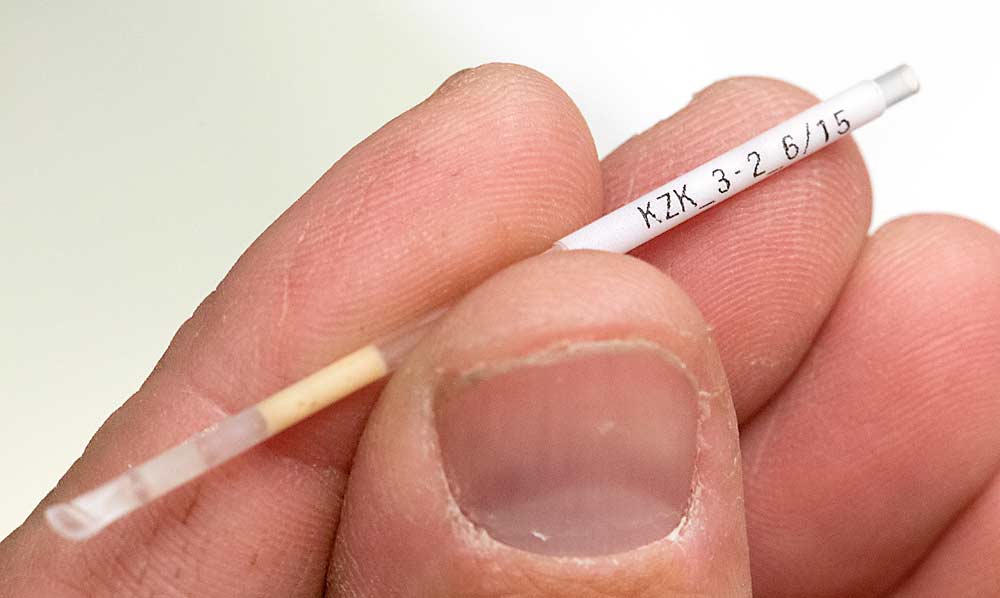

With a pipette in hand and a chorus of curious groans over his shoulders, Hopkins inserted a bead of semen into the exposed queen, with the hope of coming one drop closer to improving the genetic pool and overall health of the struggling pollinators.

This crowd-pleasing artificial insemination is just one of many ways Hopkins and fellow entomologists at Washington State University’s bee laboratory in Pullman are working to reduce the toll of colony decline suffered by beekeepers throughout the U.S.

“The goal with all of this is to make an impact and reduce the annual losses,” Hopkins said.

They collect bee semen from all over the world, freezing it for future use. They are experimenting with a derivative of fungus to use as an antiviral treatment in colonies. They are developing protocols for indoor and controlled-atmosphere storage of honey bees. And, they are moving into a new facility in the Central Washington community of Othello, so they’ll have more space for all of this bee-benefiting research.

Hopkins said he’s excited about the progress but also wishes he could deliver answers quicker. Beekeepers’ woes are well documented — varroa mites, loss of forage and diseases — and by some estimates beekeepers lose one-third of their colonies each year.

“These things are needed to help beekeepers keep their bees alive,” Hopkins said.

About that semen

The U.S. prohibits importing bees. So, since 2008, Steve Sheppard, the director of the bee lab, and colleagues have been gathering semen from remote corners of Europe and Asia, freezing it with liquid nitrogen and using it to “back breed” the same subspecies into the U.S. population, giving queen-rearing companies a deeper genetic pool from which to draw.

Hopkins joined WSU in 2010. He and Sheppard and their team have traveled almost every year since.

With each line of semen that fertilizes a queen, the first generation progeny has 50 percent of the imported genetics. The next generations would be 75 percent, then 87.5 percent and so on.

The goal is not to get to near 100 percent, Hopkins said, but to give commercial breeders more genetic tools to work with.

“We don’t want it to be just some academic exercise,” Hopkins said. WSU uses the semen to produce breeder queens, which the university will sell to queen producers and spread the progeny throughout the U.S. population.

It has worked, some. Through DNA sampling, a former student has determined that genetic diversity has increased above 1994 levels among queen producers who use WSU’s progeny.

Hopkins and crew have done this with four genetic lines, or subspecies of Apis mellifera, the honey bee.

—Ligustica: The Italian honey bee was the first subspecies to get this treatment from WSU’s bee crew in 2008, when they first received from the U.S. Department of Agriculture a special permit to import semen. The strain is known for building brood quickly, producing a lot of honey and thriving in the warmer climes of California.

—Caucasica: The Caucasian honey bee is from the Caucasus Mountains. Hopkins and the team visited the Republic of Georgia to collect semen. It’s on their travel itinerary again this year. The Caucasian was once a popular bee line in the U.S. but fell out of favor in the 1970s and 1980s because it produces propolis, a sticky substance that made hives tough to work with. Research has since shown propolis protects the colony from infections.

—Carnica: The Carniolan bee is found in many countries near the Alps. WSU’s team collected its semen twice from Slovenia. Carniolan bees function well in cooler climates, forage at lower temperatures and build up their colonies quickly in the spring. They’re typically gentle and produce a lot of honey.

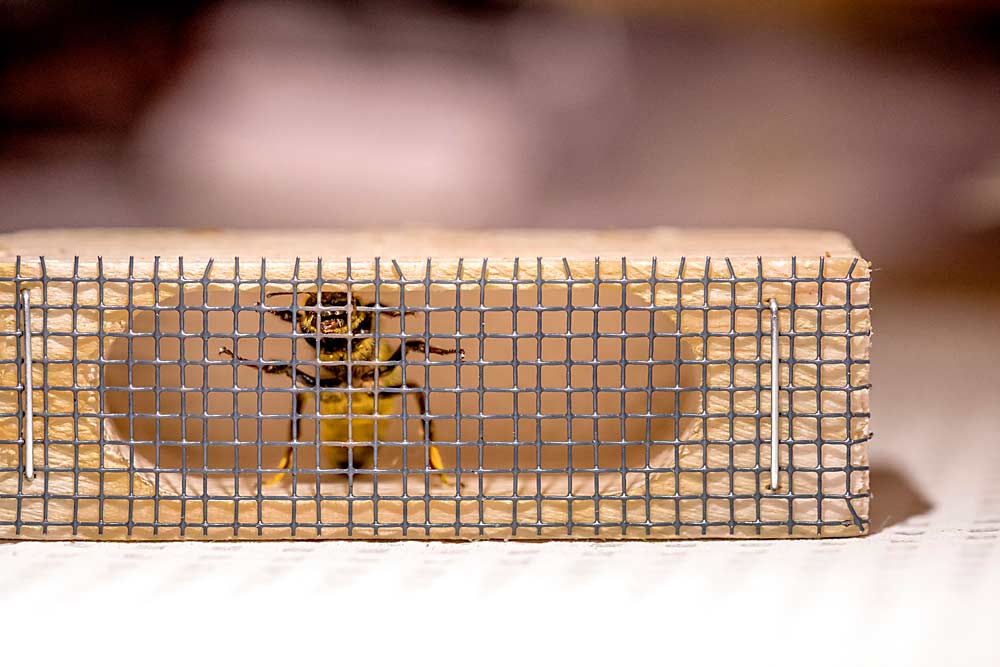

—Pomonella: This bee, which does not yet have a common name, is their most recent work. Sheppard identified it in 2003 and the team made its first collection in 2015 in the Tian Shan mountains of Kazakhstan. They’re not yet sure what genetic advantages, or “brand power,” pomonella will have, but the bee evolved in the cradle of wild apples, so it stands to reason that some of its traits may lend themselves to apple pollination. They have not released it commercially but Hopkins aims to in 2021.

In addition, Hopkins’ team has collected and frozen semen from Apis mellifera mellifera, an endangered European dark bee, in France as a conservation measure. They have not tried to breed with it.

In the end, though, all the collecting and breeding will give queen producers a more nuanced palette to breed for traits they desire, such as gentleness, productivity and pollinizing efficiency.

Add hygienic behavior to that list. Some bees are better at recognizing when a brood has a disease and will kill their own offspring to clean out a hive and remove threats. Northern California breeders have worked to improve these traits over the years.

However, varroa mites are a different problem. Researchers in Hawaii have been working on breeding bees with varroa- sensitive hygiene that disrupts the mite’s breeding cycle by removing infested brood, thereby lowering the mite population. Currently, these bees produce less honey than other honey bee strains, but breeders are working to improve that.

The trick is to find the right combination, said Pat Heitkam of Heitkams’ Honey Bees of Orland, California. His company uses WSU’s Caucasian and Carniolan bees in hive production. Each year he sends some of his virgin queens to WSU to inseminate and return.

Heitkam is the chairman of Project Apis M., a nonprofit that supports honey bee research and awareness. The group has donated funds toward several projects at WSU and to the effort in Hawaii.

WSU’s breeding just adds to his toolbox.

“When these guys add that genetic diversity, we know more what to look for,” he said. •

—by Ross Courtney

Editor’s note: The online version of this story has been corrected to reflect the difference between traditional hygienic behavior and the work of Hawaiian researchers breeding bees with varroa- sensitive hygiene.

Related:

—Bees take an indoor break

—A new, old bee

—Fighting honeybee decline with instrumental insemination — Video

Actually, glass tips used for the instrumental insemination of honey bees are commercially available through Honey Bee Insemination Service LLC at http://honeybeeinsemination.com.

I see now. Thanks for letting us know.