Shipping bays await truck drivers to haul food from the Western Distribution Services cold storage facility in 2017 near the Seattle-Tacoma International Airport. (Photo illustration and graphic by TJ Mullinax and Jared Johnson/Good Fruit Grower)

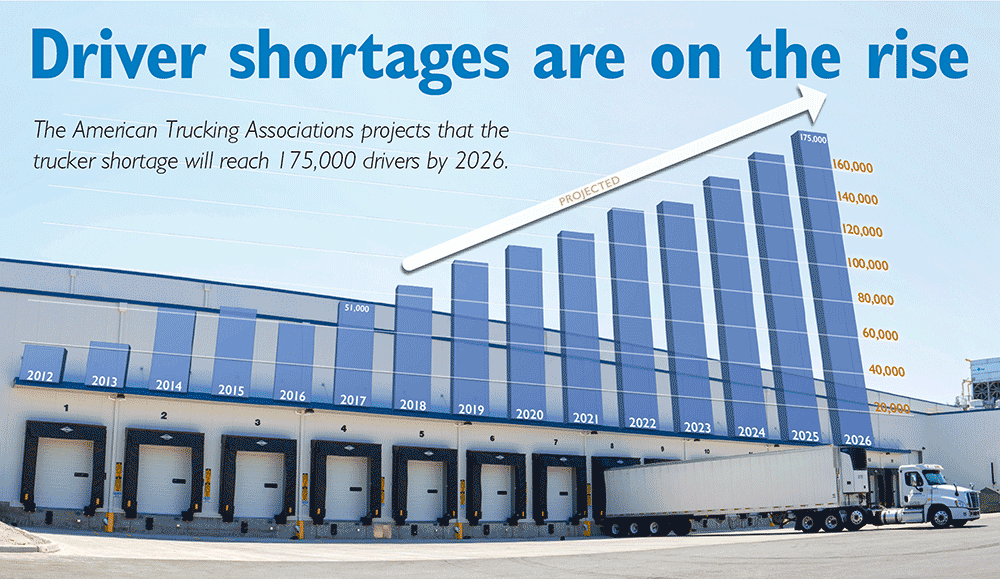

Source: American Trucking Associations

In the trucking world, the mandate of electronic logging devices may have been a talker in 2018.

But really, a dire shortage of drivers — expected to worsen in the years ahead — is the larger problem facing the trucking industry and its customers, including fruit packers. By 2026, the pool of heavy, long-haul semi and tractor drivers is expected to fall 20 percent short of the industry’s demands.

“So, you can see how big of an issue this is for us and for our customers,” said Jon Samson, executive director of the Agricultural and Food Transporters Conference, at the U.S. Apple outlook conference in Chicago in August.

Samson’s organization, which represents agricultural-specific concerns on U.S. policy, is part of the overall American Trucking Associations.

Currently, the industry faces a shortage of about 51,000 drivers. The American Trucking Associations expects that to reach 175,000 within eight years.

While Samson and other trucking lobbyists vie for tools they believe will help — more flexible rules on hours of service and lower age restrictions — fruit packers must contend with erratically high prices that growers often absorb.

“Growers, ultimately, they have to pay for it,” said Tate Mathison, director of sales for Stemilt Growers in Wenatchee, Washington. Higher shipping costs erode their returns.

Prices have been rising for a few years, with higher spikes than in the past, Mathison said. Fewer trucking companies are responding to requests for proposals, giving shippers less negotiating power than in the past. At times, it costs just as much to truck apples to Chicago as to ship by ocean to India, he said. Sometimes, he has trouble even finding long-haul trucks, forcing shipments to be delayed by a day or two.

Stemilt maintains seasonal contracts with some companies, but less predictable shipments come up outside of those contracts, causing spikes in prices.

Meanwhile, retailers are pushing the freight responsibility more toward the suppliers than in the past, he said, negotiating for a set cost and leaving the shipper to find and negotiate their own trucking. That can help warehouses logistically, which then have more say in where the truck stops on the way, but it causes even more erratic pricing, Mathison said.

Age limits

Age limitations are one of the biggest hurdles to deepening that driver pool, Samson said.

Most states require truckers to be at least 18, but the federal government requires them to be 21 to haul across state lines.

“That’s probably one of biggest things that’s plagued the industry in bringing drivers in,” he said.

However, the trucking industry sees some developments on the horizon.

One proposal by U.S. Rep. Duncan Hunter, R-Calif., would have allowed for drivers between the ages of 18 and 20 to haul across state lines under an internship program. The bill, dubbed the DRIVE-Safe Act, is under discussion at the committee level and will have to be reintroduced this year, Samson said.

Also, under different legislation — the Highway and Transportation Funding Act of 2015 — the Department of Transportation started a pilot program that allowed drivers in that in-between age group if they had experience driving for the military. It gained little traction due to the small pool of drivers in that category, but may be proposed again this year, in the next highway funding bill, Samson said.

Sampson calls the efforts steps in the right direction, even if they haven’t been codified yet.

Flexibility

Meanwhile, the industry has successfully lobbied for some agricultural-related flexibility in the hours-of-service rules that restrict drivers to 11 straight hours of driving.

For example, since 1995, federal law has included an exemption for agricultural haulers operating within 150 air miles — 172 road miles — of a farm or a retail site. That typically allowed drivers to go back and forth from the field to the warehouse without limit. In March, the industry scored a major “reinterpretation” of that exemption by regulators in the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration and now the clock starts after driving to the warehouse, loading and driving the first 172 miles, instead of before. “That was a huge piece of flexibility that they hadn’t been able to enjoy before,” Samson said.

Also, federal regulators expanded exemptions for personal conveyance that allow a driver to exceed 11 hours during unloading to safely vacate private property.

Those “common sense changes” were forced by the controversy surrounding the government’s December 2017 decision to require all trucks to track service hours with electronic logging devices, commonly called ELDs. The livestock industry, joined by beekeepers, successfully convinced Congress to delay implementing that requirement for haulers of live animals. That extension will likely continue until a transportation package this year, perhaps in September, Samson said.

The agricultural trucking industry stayed neutral on the ELD mandate but worried the agricultural exemptions wouldn’t be recognized. Since then, new devices that will annotate those exemptions are reaching the market, Samson said.

Most of the trucking talk in Washington has since shifted from the ELDs to hours of service, he said.

Also, lobbyists are trying to convince Congress to include trucks in the discussions over regulating automated vehicles. The industry is not seeking full automation, but driver-assist technology also may warrant more flexibility in hours of service, Samson said. •

—by Ross Courtney

The problem isn’t age limits it’s low pay for a horrible life style

On the average today’s t/l drivers work twice the hours of the industry standard in 1982 for 20 percent less gross income not adjusted for inflation. Factor it out and you will find to adjust for inflation driver annual wages need to double and the hours in service to the supply chain employers need to be cut by half. That is why the Ltl segment historicallly. Has a less than 10 percent turnovers do truckload has averaged more than 100 percent since deregulation 38 yrs ago. In the meantime the TL employers and the supply chain behavior has poisoned the future driver recruitment labor pool. That is why today’s blue collar people want nothing to do with trucking