The first time I watched a camera system count apples, it crawled slowly through the orchard just before harvest, weighed down by the processing speed of all the imagery. Four years later, imaging systems can whiz through orchards — recognizing the crop through the stages of development from bud (in some cases) to bin, mapping an entire block or capturing detailed sampling data.

These rapid advances in computer vision have created the opportunity for companies to develop specialized tools for orchardists, from complex, quad-mounted systems with custom lighting to smartphone-based sampling.

Today’s imaging systems are beating not just their pilot-project predecessors but also the workers who hand count buds before pruning or fruitlets before thinning, showing true promise for the future.

“In the technology tsunami we are under, the fastest advancing field is vision,” said Karen Lewis, director of Washington State University Extension’s agriculture unit and a longtime researcher of orchard technology.

Just a few years ago, good imaging required narrow canopies and round, red apples. Now, it’s working in almond groves and stone fruit orchards. Many of the technological hurdles have been solved, according to sources for this story, but the race is on to find the right applications for vision systems that can deliver growers results and financial returns.

“We’re really looking at the technology. It’s really cool, but we’re not going to buy anything just because it’s cool,” said Gilbert Plath, a fourth-generation grower and member of the Washington Tree Fruit Research Commission’s technology committee. “We’re trying to flesh out who is going to be the winner, what’s the price point, what’s the most valuable data.”

Value vision

At first, computer vision was pictured as a yield estimation tool, to help growers plan harvest and sales desks to prepare, said Dennis Healy, CEO of FarmCloud, an ag data consulting firm. There’s certainly value in that, but deploying those increasingly capable analysis tools earlier in the season, for example, gives growers the chance to use the data to better manage their crop loads and increase returns.

After evaluating vision systems for several years, Healy partnered with Australia-based Green Atlas to be the U.S. distributer for their orchard vision system. The data it provides can, for example, show growers where crews need to hand thin, he said, saving significant labor costs. FarmCloud will sell the systems or offer imaging as a service, as will another digital ag service provider, Walla Walla, Washington-based innov8.ag.

A lot of the orchard vision companies Good Fruit Grower spoke with now target crop load management applications for their technology.

“After four years of showing growers that we can identify fruit and size it, growers said, ‘This is what we really want,’” said Scott Erickson, director of business development for Farm Vision Technologies, a smartphone-based vision system that started with University of Minnesota research.

Erickson said the young company offers a commercial yield estimation tool — attach the smartphone to an ATV and scan the rows to record video for analysis — and is collaborating with Michigan State University researchers to develop a fruitlet sizing tool that could replace tedious caliper measurements.

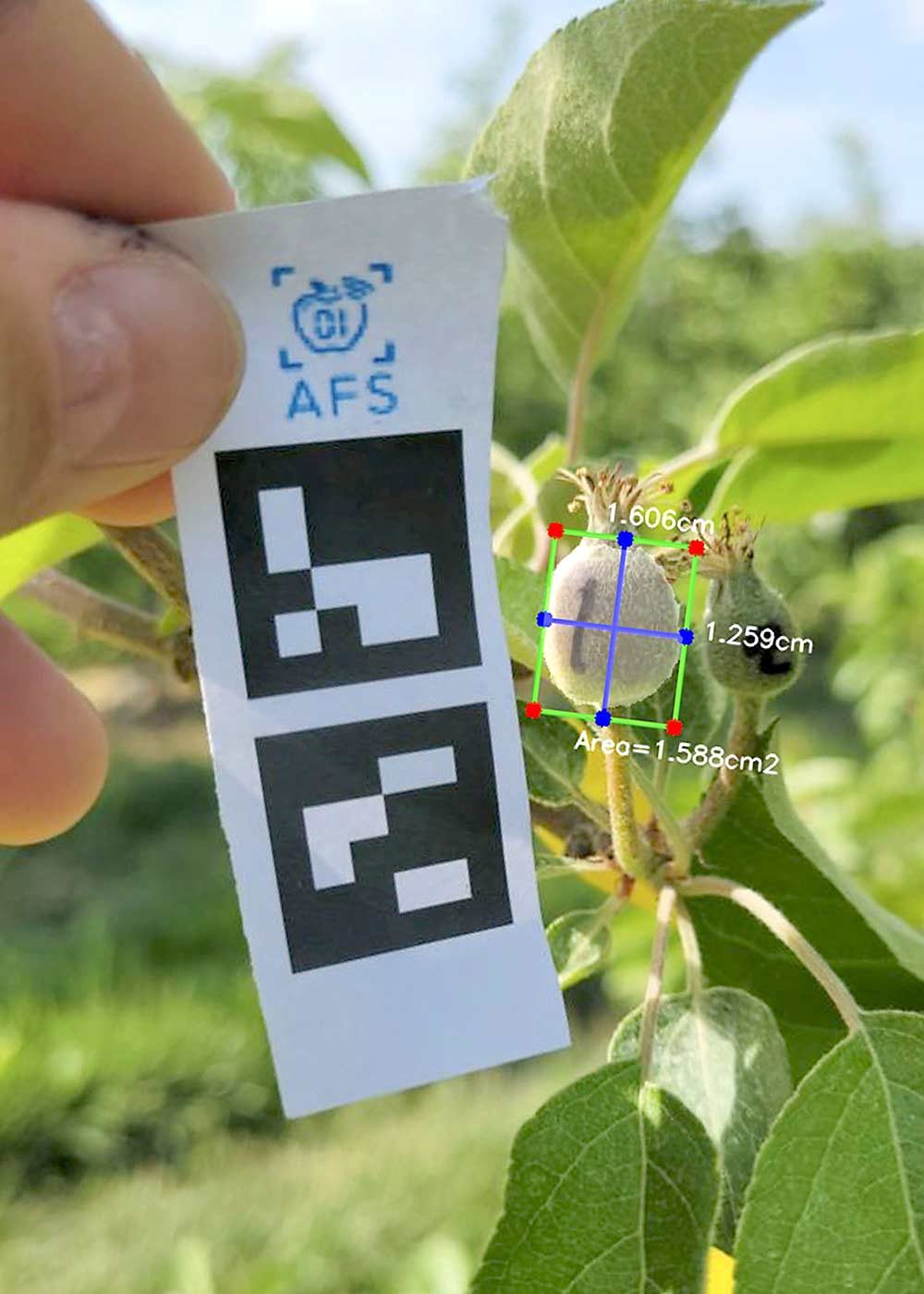

Automated Fruit Scouting, a Washington-based company, skipped yield estimation entirely and built its approach — orchard sampling via smartphone photo — around crop load management.

“Unlike our competitors, we do not look at part of the tree and estimate the crop load. We look at the tree through the season, like equipment on the production line, so we don’t ever have to estimate,” said the company’s founder, Matt King.

He designed the data collection around crop load management models. A person walks the row and uses a smartphone to photograph trees. The image analysis first measures the trunk cross-sectional area to predict the optimum crop load. In subsequent passes, it counts buds, followed by flowers and then fruitlets, turning the analysis into management recommendations for each thinning step until the trees reach the optimum crop load.

“We cost less than doing it with a clipboard,” King said. The company, which launched last year, charges $1 for every tree sampled each season. “We will save you money on labor by making it take less time, but then if you use that information to hit your production targets, it will make you money.”

Moog, a New York-based engineering firm best known for military contracts, began work on computer vision for orchards several years ago. The goal: Develop an autonomous camera system that counts the buds on every tree to enable precision pruning and thinning to optimize crop load and, therefore, fruit quality.

“Instead of counting a dozen trees and then decide the management process, why can’t we count each individual tree and feed that information back to the laborer who knows what to do?” said Chris Layer, the principal engineer on the project. They are in pre-commercial trials and partnering with Cornell University. “We believe we know how to do this, so the question is: How much value would it provide?”

Tech specs

King, of Automated Fruit Scouting, based his approach to computer vision on that applied to a production line by Boeing and other manufacturers.

“Computer vision has changed every industry except agriculture — until now,” King said. “Plants are really hard to measure — way harder than widgets. They change shape, they change color.” But the value of precisely measuring production processes is the same, he added.

That seasonal change limited computer vision for a long time, said Steve Scheding, the co-founder of Green Atlas. Engineers previously had to write a set of rules to teach a computer what an apple looked like — round, red and so forth — but now imaging uses a process called deep learning. Basically, give a computer enough pictures of apples and it learns to find the patterns.

“You no longer have to explain what an apple looks like if the branch is blocking half of it,” Scheding said. With enough images from every phase of the season, the computer can learn to see bloom development or fruitlet growth, rather than be confused by it. Given enough images, systems with deep learning can even learn to count avocados. “If you want the worst green on green you could have, it’s avocados,” he said.

Today, the harder problem remains ensuring that every image is a good one, he added.

“I’m really jealous of factory computer vision because they literally have floodlights on everything with no shadows,” Scheding said. Green Atlas’ approach to that: strobe lights that flash with every photo, to compete with the sunlight. Day or night, it looks the same.

But Automated Fruit Scouting, Farm Vision and others believe a smartphone camera can get all the data growers need, with no extra lighting. Smartphone-based systems are more affordable and can be used in multiple locations at once, they say.

“We don’t have to iterate and invent the next best camera; there are already other companies doing that,” said Erickson. “We can focus on what to do with that data that someone on the farm can utilize.”

Just don’t take photos directly into the sun, King said, and his company’s AI can handle the variation in lighting.

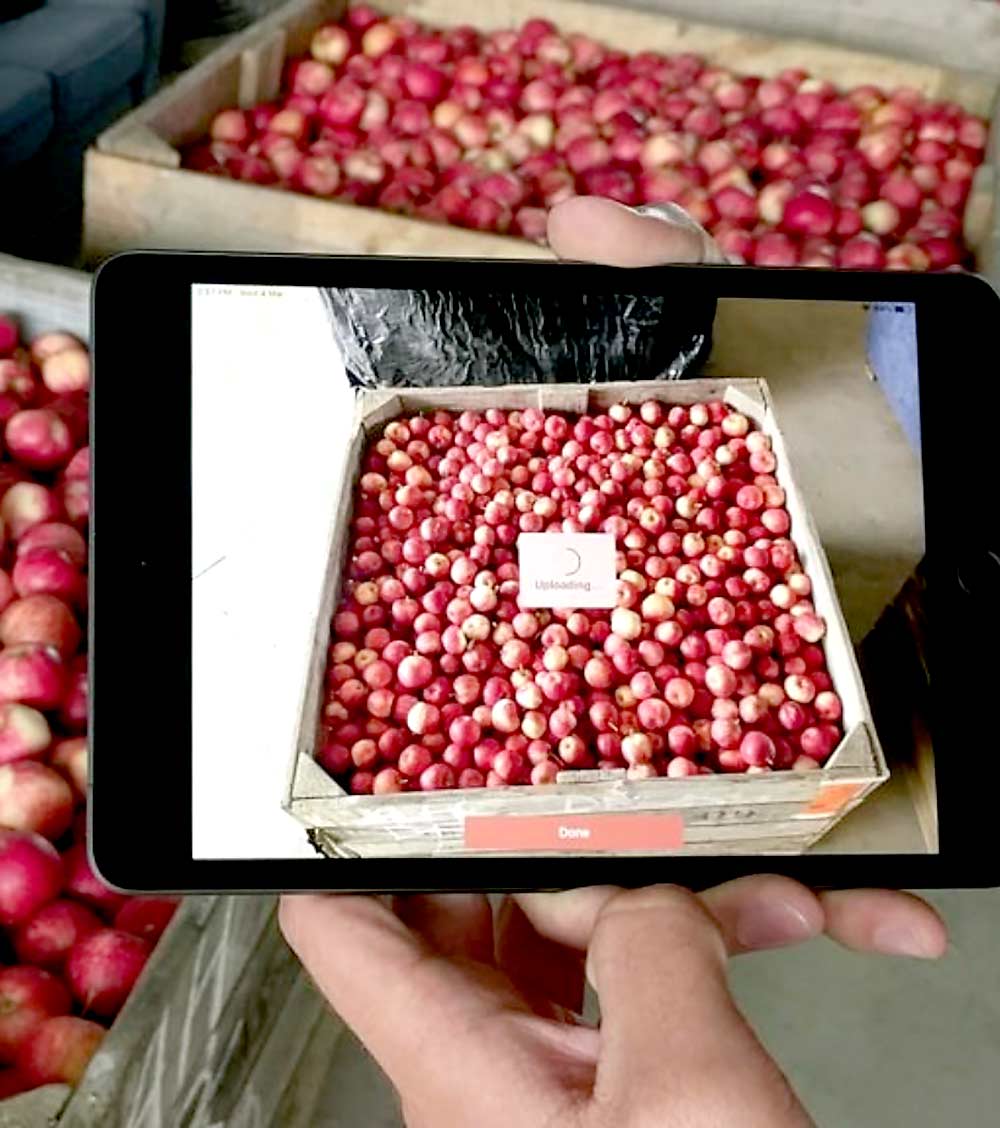

Another smartphone system focuses solely on imaging already-picked fruit. Snap a photo of the top of the bin and Spectre, a vision product from Hectre, a New Zealand-based orchard management platform, can size or color-grade fruit in seconds, said company spokeswoman Kylie Hall.

It’s simple, but it can save companies a lot of money to have that information well before the fruit hits the packing line, she said. Defect identification and sizing for cherries are in the pipeline.

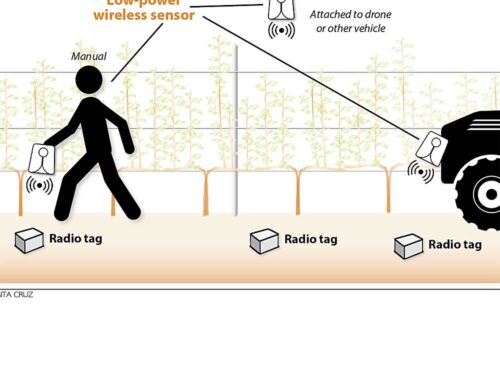

Also arriving in orchards: camera systems mounted to autonomous tractors, sprayers and other equipment. (See “No drivers needed” and “Collaborate to innovate.”) Those manufacturers say they are eager to partner with vision companies to share the image data their equipment already collects as it moves through orchards for data extraction, when possible.

Data to decisions

The promise of precision agriculture is that data collected by the image systems can inform management — but at what level? Do growers want to manage on a tree-by-tree basis?

King says that’s the goal. Right now, he recommends sampling 5 percent of the trees in a Gala block and 20 percent in Honeycrisp.

“Where we think this goes in five or 10 years is every tree gets imaged” and managed to its specific capacity, he said. “That’s the whole point of precision crop load management.”

Similarly, Moog envisions delivering tree-specific pruning and thinning recommendations, thanks to robust GPS that can differentiate trees at 18-inch spacings. Eventually, that information would be the foundation of robotic pruning machines, but in the intermediate phase, it could be delivered to crews via headset or smart glasses.

“Right now, we’re in the phase of counting what’s actually on the tree and coming up with a process to communicate that to the laborer,” Layer said. “Lots of people make cameras, lots of people make AI. It’s putting this all together and getting it to be robust — that’s the real challenge.”

Another emerging company, Verdant Robotics, of California, hopes to put the precision vision information to use immediately with its spot sprayer technology. The idea is that if the camera sees too many blooms or fruitlets on a tree, it can precisely spray to thin just that cluster, said Curtis Garner, company co-founder and chief operating officer. Still in the pre-commercial phase of the project, the company is exploring the possibility of precision pollen, PGR or antibiotic applications as potential tools as well, he said.

On the other hand, Green Atlas’ technology delivers zone maps, showing areas of relatively higher and lower bloom density, for example. Growers aren’t yet managing at an individual tree level, Scheding said, so more detail isn’t valuable. But the zoned maps can be connected to a variable-rate sprayer with existing technology.

“Data intrinsically has no value. It’s what you do with it,” Scheding said. “What will you do differently? That’s where the value is derived.”

Plath agreed. He’s evaluating Green Atlas and Automated Fruit Scouting this year, among other technologies.

“We need to see somebody come to us with the whole picture, or work with other companies we are using, like the variable-rate sprayer or spreader, so there is an easy way for the farmer to pull it off,” he said. “And we’re getting there.”

—by Kate Prengaman

Really interesting,

do you know similar technologies for using in fruit tree nursery? For evaluation and counting of fruit nursery trees during growing season in the big nursery.

It would be great technical tool for nurserymen.