As Pacific Northwest growers look for ways to stretch their reduced irrigation allotments during the worst drought in decades, all steps that conserve water–no matter how small–should be considered.

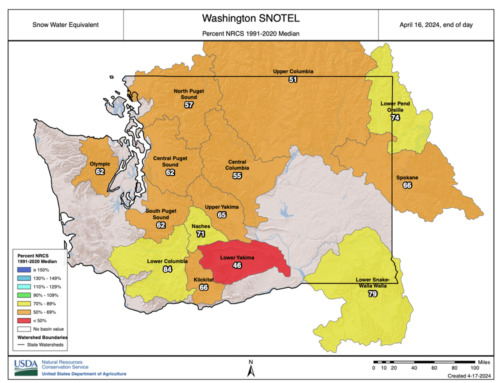

One of the areas hardest hit by the lack of winter precipitation is land in central Washington irrigated by the Yakima River Basin Irrigation Project.

Two irrigation districts operated by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation–Kittitas and Roza–anticipate receiving between 8 and 28 percent of their normal water allotment, depending on spring rains and temperatures.

The Roza Irrigation District, serving 72,000 acres in Yakima and Benton counties, will release detailed shut-down information in June, but officials predict water delivery interruptions will occur throughout the season.

In Kittitas, the district projects water deliveries will cease by the end of June. Tough time It’s a frustrating time for growers.

Irrigation districts with proratable or junior water rights are working to secure additional water through purchases and water transfers. Farmers with wells are seeking permits from the Washington State Department of Ecology for emergency use of their wells.

Numerous unknown factors, like rate of snowpack melt, hot spells in the summer, and timing of water delivery all will affect the severity of the drought.

“Growers are either pulling their hair out trying to figure out what to do or they have their hands in their pockets in a wait and see mode,” said.Jack Watson, Washington State University (WSU) Cooperative Extension agent for Benton County.

Until growers know the extent and nature of water rationing, the following early season cultural management practices are suggested by WSU Cooperative Extension to maximize water efficiency:

- Fertilize and prune trees and vines to produce moderate growth and yields.

- Keep cover crops mown; plan to spray them out if drought conditions become severe. Keep area around trees and vines, especially young trees or vines, free of weeds and grass.

- Thin crops to moderate levels.

- Improve irrigation application efficiency.

- Implement irrigation scheduling. “Don’t try to take big crops this year–moderation is the goal,” Watson said. He added that if growers haven’t already implemented irrigation scheduling and improved their irrigation delivery system so water is applied when it’s needed and as efficiently as possible, now is the time. Soil moisture should be constantly monitored to ensure that water is applied only when needed or at strategic times.

Antitranspirants, which work by keeping the plant’s stomata closed longer, may also be a way to reduce or conserve a plant’s use of water.

“All these little things–moderate crop loads, managing cover crops, antitranspirants, irrigation scheduling–may provide marginal water savings by themselves, but when combined together, they all add up and may make a big difference.”

Critical stages In vines, the most critical period for water is during late spring and early summer when shoots grow rapidly and cell division occurs in the berries. Severe water stress at this time can result in small berries and poor berry set.

The second critical water period is when cell expansion takes place in late summer.

Severely withholding water at this period can result in reduced berry size and even delayed maturity. A critical fruit development period in tree fruit begins about four weeks after full bloom when rapid cell division within fruit takes place.

Water stress at this time impacts the amount and ultimate size of fruit. However, the most critical time is during final fruit swell or fruit finishing. In cherries, final fruit finishing occurs during the last three weeks prior to harvest; in apples, it’s during the last two months. In stone fruit, this is after the pit hardening stage.

Both fruit size and quality can be reduced if severe water stress occurs during final fruit swell. Eliminating the final fall irrigation has fewer detrimental effects on fruit production than withholding water during the growing stages.

However, it sets up the orchard and vineyard for potential problems by going into the winter with dry soil and roots. Vines are especially sensitive to cold temperatures and are more likely to suffer from winter injury if the root zone is dry.

Irrigation system According to WSU literature, tests have shown that many irrigation systems used in orchards could be improved to increase application efficiency by at least 50 percent.

Even modern irrigation systems operate at less than 100 percent efficiency. One way to check efficiency is to make sure application amounts and pressures are consistent throughout the irrigation system.

“Drip irrigation and irrigation scheduling are things that ought to be looked at by growers,” Watson said. “especially Concord growers that may still be using overhead sprinkler or rill irrigation systems. Drip irrigation and irrigation scheduling can really help reduce water use.

Growers can get by on a fraction of the amount of water they’d be using otherwise.”

A portable drip irrigation system can be set up quickly and inexpensively. A pump and filtration system can be mounted on a trailer, powered by a diesel or gas generator, and moved from block to block for irrigation. Various types of drip tape are available at irrigation supply companies.

Drip irrigation works best if low levels of water are available for an extensive part of the growing season.

Rill or sprinkler irrigation may be best if full water delivery is available for short periods. If a long period is expected between irrigations, orchardists and vineyardists are advised to wet more of the soil profile to ensure adequate moisture reserves.

Survival Some orchardists have discussed eliminating all fruit from their trees to reduce water requirements. However, Watson believes that only a marginal case can be made for reducing the entire crop. While fruit act as a sink during the growing season, storing water and nutrients, some water is likely given back from the fruit to the tree for its survival.

“If it comes down to survival of the trees, ‘dehorning’ or heavy pruning that reduces tree canopy and water needs is always an option,” he said.

Fruit trees under drought stress, especially those that have been “dehorned,” are more susceptible to sunburn and should be protected. Whitewash or diluted latex paint should be applied to exposed portions of main scaffold branches.

This summer may also be time to consider removing older, less profitable blocks of fruit to shift water to more profitable areas of the orchard or vineyard. Watson said.that some loss of trees this summer is likely.

“But trees are amazing in their ability to survive. What we found from the last drought is that while the current crop is disturbed, the trees came back fine the following year. In fact, they tended to set more fruit than normal and growers had to watch thinning and crop loads carefully.”

He added that vinifera wine grapes tend to survive water stress even better than fruit trees, with the exception of Concord labrusca-type vines.

Unless there are extreme drought conditions, vine survival is probable, though crop quality and yield may suffer. Concords, he explained, are native to the eastern United States and have shallower root systems than wine grape varieties.

“They don’t forage for water as well as wine grapes,” he said. Options Dr. Edward Proebsting, retired WSU horticulturist, experienced several droughts in the Northwest during his tenure with the university.

Several of his research projects dealt with water management during short water years. “We looked at fruit removal in our research trials,” he recalls. “Effective crop removal was found to have very little to do with tree survival but a whole lot to do with management of the crop.”

Fruit do return some water back to the tree if the tree is in survival mode, “but the amount is trivial,” he added. “The biggest problem is that with a drought, people’s hands are pretty much tied as to any options in timing of water,” Proebsting said.

In the past, irrigation districts have been unable to provide water throughout the season and must empty the canals when the supply runs out. “If you can do it, growers should try to save some water for finishing the fruit,” he advised.

He encouraged orchardists to thin aggressively. He noted that although water stress will reduce growth rate and fruit size, “you can size a smaller crop if you thin heavily.” Growers could do a lot of things if they had complete control of the water system and when irrigation deliveries were made.

“You could engineer your irrigation system to fill the soil profile at the start of the season,” Proebsting said. “You could invest money in soil monitoring, and time water application at critical growth stages.”

Unfortunately, growers usually have few options during a drought year, he noted. “But if you’re thinking that removing all fruit will solve your problems, it will do little to save the tree,” he emphasized. “I’d thin aggressively and make my thinning mistakes on the side of taking too much off. I’d leave some crop on the trees to help pay the bills.”

Visit WSU’s Web site for more drought-related news and water conservation tips at: http://drought.wsu.edu.

Hi Melissa,

We live in Queensland Australia and are experiencing a severe drought atm and was wondering if you had any tips for moisture level requirements for stonefruit trees during dormancy . We normally try to have a full profile of moisture for the early varieties before budswell which is about 4 weeks away but have totally dry profile atm. Water is short and was wondering wether we should apply some now or if the trees don’t require any till just before movement..

Hope you can assist.

Kind Regards,

John Pratt