Michigan State University Extension tree fruit educator David Jones, right, leads a grower class in 2017. After fire blight became an issue in many Michigan apple orchards in 2018, Jones and a statewide team began searching for the cause of the outbreak. Jones focused on West Central Michigan and whether streptomycin resistance may have played a role. (Courtesy David Jones/MSU Extension)

Fire blight raced through many Michigan apple orchards in 2018.

Conducive weather during bloom was one part of the cause. Another is the increasing shift toward high-density apple orchards in new growing regions of the state, including dwarfing rootstocks that are blight-susceptible and small cultivars that make it easier for blight to disperse from the branches to the main trunk, where it can kill the tree.

“We saw widespread damage across the west-central region, and this was true in a lot of parts of Michigan,” Michigan State University Extension tree fruit educator David Jones said at the Great Lakes Fruit, Vegetable and Farm Market Expo in December in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Anecdotally, Jones said the worst damage seemed to be in locations where streptomycin use had been particularly heavy. A couple of growers in the west-central region who have had high-density plantings for a longer time and have been using Kasumin (trade name for the alternate antibiotic kasugamycin) didn’t seem to have issues.

To find out whether streptomycin resistance may have actually played a part in the fire blight upsurge, Jones and his group visited the west-central Michigan farms that were affected by the outbreak, collected bacterial samples from each, and tested them for resistance.

They found strep-resistant fire blight isolates in more than half of the sites. It also was pervasive across the region.

What should growers do to prevent a repeat of 2018?

Growers who are shifting to high-density systems must consider the impact of tree vigor on disease management, he said.

“Obviously, we are trying hard to push these trees over the top wires as quickly as possible, and this is the right thing to be doing in the sense that we need to be getting our money back,” he said, “but we also need to understand that the strong push in vigor makes thinner cell walls, which makes the plant more susceptible to attacks from fire blight and it also expands that period of shoot blight susceptibility, so the window during which you should be concerned about fire blight significantly widens as well.”

That means growers should think about curtailing vigor when the risk of fire blight is high and reevaluate their spray programs to make sure they are doing everything possible to keep the disease at bay.

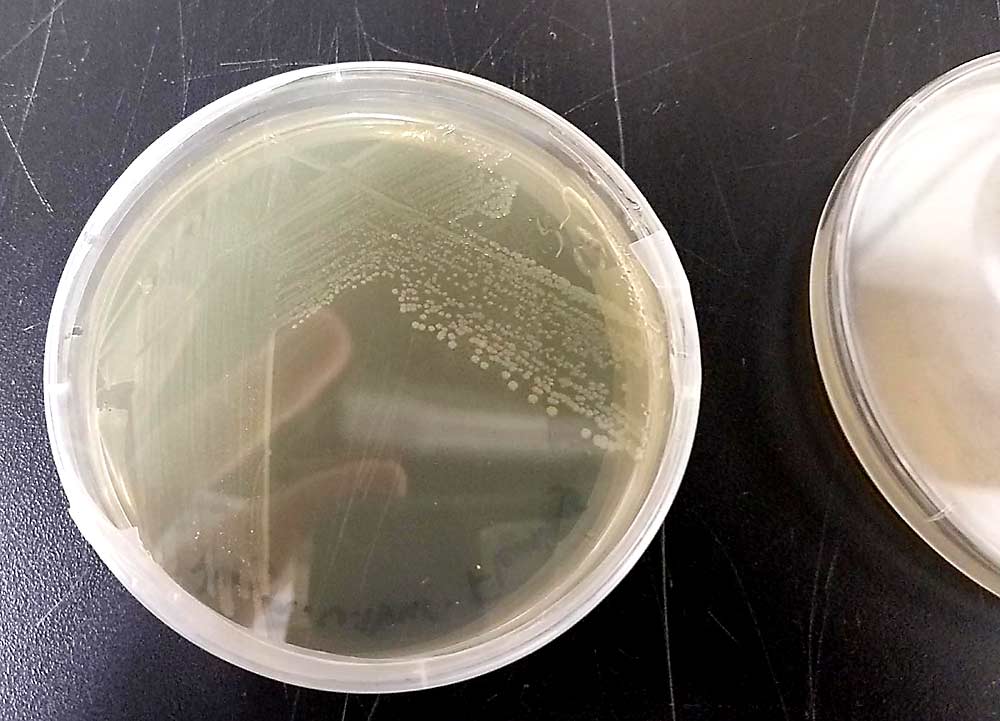

Fire blight pathogen on a Petri dish. (Courtesy David Jones/MSU Extension)

Staying on top of blight

Given the results of their strep-resistance study, Jones said Michigan growers should assume that streptomycin “is probably a risky option at this time,” especially for use on young, susceptible acreage.

“That’s not to say that it’s 100 percent not going to work in all situations and regions, but given how prevalent resistance was (in 2018), your odds are not excellent,” Jones said. Instead, he suggested Kasumin as the premier alternative to streptomycin, especially in high-risk situations.

Another possibility is oxytetracycline (Mycoshield), but he cautioned that this is a bacterial inhibitor, not a bacterial killer, and appropriate only in low- to moderate-risk situations. In other words, he said, it will only slow things down when bacterial populations are lower.

The plant bioregulator prohexadione calcium (Apogee and Kudos) is also a good option to reduce shoot blight risk, but he noted that Apogee must be applied multiple times every year.

On nonbearing trees, he said, copper also works against fire blight because growers do not need to be concerned with fruit russet, a common side effect of in-season copper usage.

Many growers are interested in Actigard (acibenzolar-S-methyl), which boosts a plant’s natural defense systems, but Jones said the jury is still out on how consistently it will work against fire blight in apple orchards.

Although MSU plant bacteriologist George Sundin had some promising results with an Actigard/Apogee combination approach in 2017, Jones said, it’s still too early to make specific recommendations on Actigard, especially as a substitute for a solid antibiotic.

Despite fire blight’s frustrating prevalence and strep-resistance in the 2018 season, Jones emphasized that it is a very manageable condition in Michigan apple orchards, and growers can take steps to prevent a repeat performance in 2019.

“It requires doing your homework and understanding the relative risks of your region, which antibiotics are the best and which are going to be risky, and the horticultural practices that limit vigor and reduce tree susceptibility to this disease,” he said. •

—by Leslie Mertz

Related:

—Organic control options for fire blight

—Managing fire blight for the conventional grower

—Stopping shoot blight

—Video: Fire blight management tips from the 2018 WSTFA Hort Show

Leave A Comment