Gala apples ripening before harvest in a Wapato, Washington, orchard on August 24, 2017. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

The three parties to the North American Free Trade Agreement — the United States, Canada and Mexico — have entered negotiations on a new deal, so it’s no surprise NAFTA is the hot topic this week at the 2017 USApple Outlook conference in Chicago.

The stakes are high for the U.S. apple industry, which exports 30 percent of its crop, with Mexico and Canada its top two markets.

The impetus

President Donald Trump has made reducing U.S. trade deficits a priority of his administration. He has referred to NAFTA as a “catastrophic” trade deal for the U.S., pointing to a $63 billion bilateral deficit with Mexico in 2016, and earlier this week said the U.S. would probably terminate the agreement at some point. One driving force behind the rhetoric: the loss of U.S. manufacturing jobs.

To economists, a trade surplus or deficit shouldn’t be the only measurement of whether a trade agreement is healthy, but it is one of the metrics being evaluated now, said Veronica Nigh, economist for the American Farm Bureau Federation. She noted that the U.S carried a $2 billion surplus over most of the life of the agreement; over the past two years, commodity prices have tanked and, combined with a strong U.S. dollar, has eaten away at the U.S. surplus.

Still, for more than half of U.S. states, both NAFTA partners are the top two markets for exports.

The agriculture industry has largely benefited from the 1994 deal, though most experts say it, at 23, could stand a slight revamp. “I’ve described it as an A- agreement that we’d like to bring up to A,” Nigh said. “Relationships change over time and trade agreements are no different.”

John Cruickshank, consul general for the Consulate General of Canada in Chicago, agreed that a new NAFTA must modernize, in part to ensure an internationally competitive technology sector for all three countries. Among other changes needed, he said, are freer markets for government procurement, easier border crossings for residents among the three countries, as well as changes to the dispute resolution process. Canada also wants to make NAFTA more progressive, with strong labor and environmental safeguards, he said.

Together, the three countries constitute the biggest economic zone in the world. Businesses have developed continent-wide supply chains to produce the highest quality goods at the lowest price for domestic consumption and for export, and kept jobs in North America that would have otherwise been lost to offshore competitors, he said.

Karen Antebi, economic counselor for the Ministry of Economy of Mexico’s Trade and NAFTA Office, said a NAFTA 2.0 should strengthen the competitiveness of North America, allow more inclusive and responsible regional trade and address the 21st Century economy. But in a zero-sum trade goal, she said, “I fear the only winners will be our overseas competitors. Globalization and technology are here to stay. A strong North America is key to our ability to compete in world markets. Trade is part of the solution.”

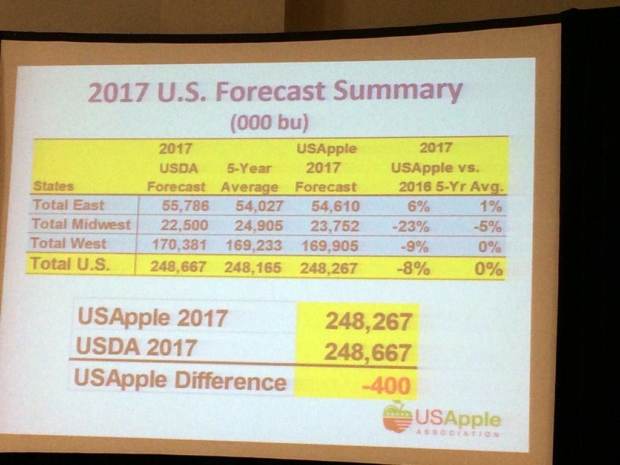

A summary slide from the 2017 USApple forecast. Photo by Shannon Dininny.

Mexico buys one of every four U.S. apples bound for export, 8 percent of total U.S. apple production, at $230 million, she said. “Prosperous growth in Mexico means there will be more opportunities for apple exports.”

Potential changes

Among the changes that Nigh said could potentially benefit the apple industry are sanitary and phytosanitary rules similar to those that would have been enacted under the 12-nation Trans-Pacific Partnership—an agreement President Trump withdrew the U.S. from shortly after taking office. Others include a rapid response program for perishable products to resolve border issues more quickly, and an integration of each country’s border rules to speed crossings.

One idea being pushed by some specialty crops is raising concerns among other agricultural interests, including the apple industry. Some growers, including tomato growers in the southeastern U.S. who contend they are being harmed by Mexican imports, want changes to rules governing anti-dumping and countervailing duties to better protect them during their season.

Critics argue the idea denigrates the benefits of free trade by carving out geographic exceptions, and that trading partners are likely to apply the same rules for other crops in retaliation. An example: Mexican apple growers in the state of Chihuahua, who have brought multiple dumping claims against the U.S. in the past two decades.

The growers’ association there has a new president who grows 100 percent organic apples and is more interested in seeking ways for growers there to differentiate their products, rather than to block trade altogether, said Leighton Romney of Paquime. That being said, seasonal considerations are No. 1 on their list, he said. “They want a seasonal tariff in the negotiations.”

Looking ahead

The negotiations are happening behind closed doors, with the second and third rounds scheduled for September, and all three countries say they want an agreement by the year’s end. That’s particularly crucial for Mexico, which faces a presidential election next year.

In the meantime, are there any potential deal-breakers for President Trump?

The target is a moving one, Nigh said, but she noted that many trade agreements are negotiated under one administration and passed under another, often with very few changes.

“My hope would be that the NAFTA negotiations follow a similar pattern, that if there have to be some changes, they wouldn’t have to be dramatic for the administration to be happy with them.”

easier border crossings for residents among the three countries? Huh? Sounds like a political party’s slogan. Tell me how easier residential border crossing helps trade?

“Wealthier Mexican can afford to buy our fruit” Population of Mexico is 127 million. Population of US 300 million. Make American richer by having our jobs stay here so American have more income to buy apples!