In the apple orchard of the future, what is the pollinizer?

It certainly isn’t Manchurian crab. The discovery that it harbored the quarantine pathogens speck rot and sphaeropsis, responsible for the temporary loss of Chinese market access in 2012, didn’t bode well for the dominant pollinizer in Washington orchards.

The industry’s desire to replace Manchurian sent Washington State University professor of tree fruit physiology and management, Stefano Musacchi, on the hunt to find the next generation of pollinizers. He isn’t yet ready to make recommendations to growers — a select few promising new candidates remain under evaluation — but the project has also resulted in a better understanding of the underlying genetics that make a pollinizer a good match, which will help growers make better planting decisions now.

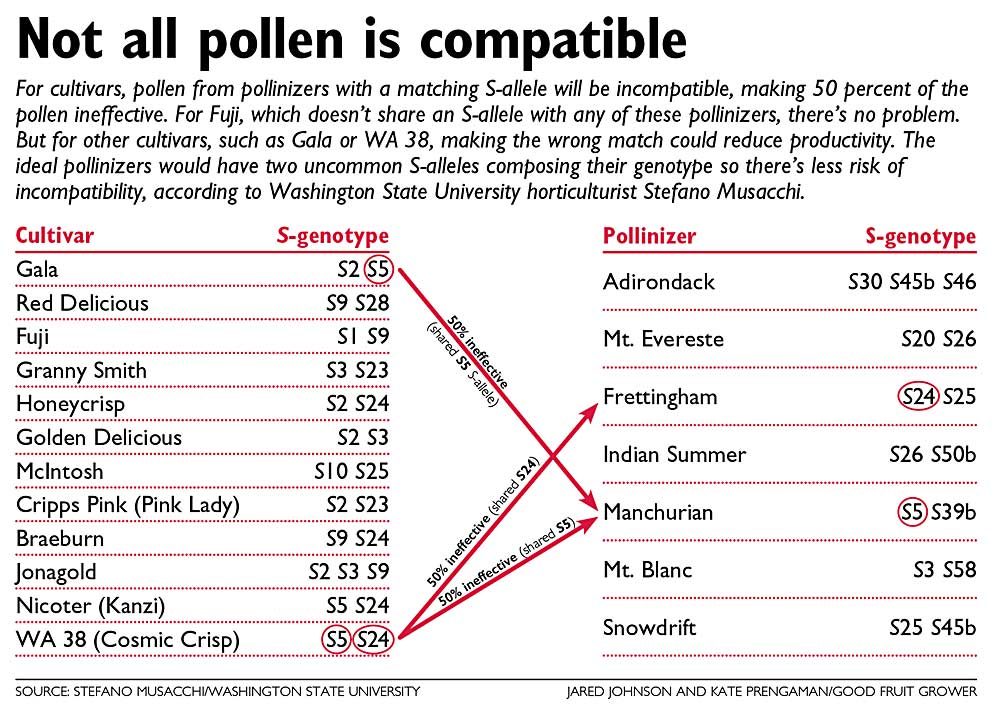

Traditionally, bloom timing guided pollinizer selection, but cross-pollination works because the pollen is identified as different by the pistil. The genetic basis controlling this mechanism comes from what’s known as the S-genotype, which is made up of two different S-alleles. Researchers have identified dozens of S-alleles in the Malus genome, but sharing an S-allele creates incompatibility because the tree will identify the pollen as its own.

It’s rare to share both S-alleles, especially when comparing crabs to cultivars, but sharing one is enough to make half the pollen in the orchard impotent.

“Just because you see all the flowers, that doesn’t mean all your pollen is working,” Musacchi said. The ideal pollinizers would have rare S-alleles, so there is less risk of overlap.

Manchurian shares an allele with both Gala and WA 38, the new WSU-bred variety to be sold under the brand name Cosmic Crisp. Even though pruning the crab apple has been shown to sufficiently reduce disease risk in existing orchards, growers need other options, Musacchi said.

Other pairings should be avoided as well: Honeycrisp, Braeburn and WA 38 all share an allele with Frettingham, while Granny Smith shares an allele with Mt. Blanc.

For WA 38, he recommends Snowdrift, Indian Summer and Mt. Evereste, which also shows the most fire blight tolerance.

“Pollinizers have specific windows, so you need to mix more than one to cover a larger blooming window,” he said. “Having two or three pollinizers in the orchard is a risk-minimizing tool.”

This research into genetics will definitely benefit growers as they plan new plantings, said Gary Snyder of C&O Nursery in Wenatchee, Washington.

“Instead of just going on and saying, ‘Well, these bloom at the same time, so it’ll be fine,’ it’s looking at all these new pollinizers and saying that when somebody puts in a growing contract for variety A, they should be getting the correct pollinizers B and C,” he said. “It’s a way to protect the grower on his future planning and planting.”

New options would be welcome as well, Snyder said. They are no longer producing Manchurian, except for the occasional request, and instead lean on Snowdrift, Mt. Blanc, Mt. Evereste and Indian Summer.

On their quest for new options, Musacchi and his team have evaluated thousands of trees over the past five years to whittle down 30 different crab apples to the promising few. The project started with 30 genotypes from J. Frank Schmidt and Son Co. — an Oregon ornamental tree producer and crab apple breeder — and evaluated them for winter hardiness, tree size and shape, growth rate, annual bearing, good flowering, bloom time, fruit size, disease resistance, pollen viability and compatibility, along with low maintenance requirements, Musacchi explained.

“Every step, we lost a few genotypes,” he said, and that process of elimination narrowed the talent pool down to just six genotypes, which he declined to name since he’s not ready to recommend them to growers just yet.

These survivors don’t harbor the quarantine rots that made Manchurian problematic, and they also appear tolerant of fire blight and have good pollen quality, Musacchi said. Uncommon S-alleles offer another advantage.

Now, the six promising genotypes need performance evaluations through field tests. The first five-year project was funded by the U.S. Department of Agriculture as part of a $1.9 million grant to address the market access issues posed by Manchurian, but Musacchi is now seeking funding for the next phase of evaluation.

“It takes time, just like a breeding program,” he said, to understand how these crab apples will perform in the pollinizer role.

But, he’s optimistic. “These six genotypes are the future, in my opinion,” he said. •

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment