Vitis vinifera plantings in Michigan have grown hand-in-hand with the state’s wine industry over the past few decades, to the point where vinifera grapes are now the most common wine grapes planted in the state, said Paolo Sabbatini, an associate professor and viticulture specialist at Michigan State University.

Though it’s been shown that vinifera grapevines can survive Michigan’s brutal winters, that survival is not guaranteed. The location of plantings is crucial. Using new, cutting-edge tools, Michigan State University’s Remote Sensing and Geographic Information Science and Outreach Services is working with the state’s wine industry to fine-tune the search for optimum vinifera sites.

RS&GIS specializes in geospatial sciences, studying “how things interact over space” for a variety of fields, including agriculture, said Erin Bunting, assistant professor and group director.

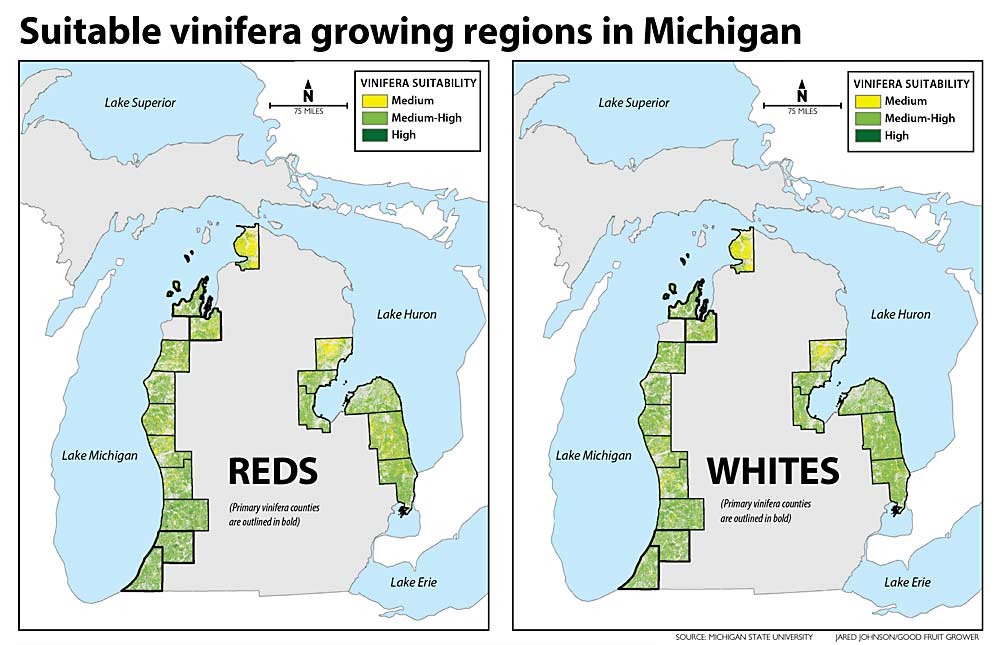

RS&GIS has created a mapping tool (find it at rsgis.msu.edu/research/vinifera) that Michigan growers can use to explore the suitability of specific areas of land for vinifera plantings. In a broad sense, the tool confirmed some things the industry already knew: The best sites lie along the Great Lakes, which moderate surrounding temperatures. If it wasn’t for the unique climate provided by the Great Lakes, vinifera vines could not be grown so far north, said Bob Goodwin, senior geospatial analyst with RS&GIS.

However, proximity to the Great Lakes does not guarantee a site’s suitability for vinifera. The tool helps measure other contributing factors as well, though Goodwin stressed that it doesn’t tell the whole story. The data generated by the tool complements but does not replace local knowledge, Goodwin said.

“It is fairly easy for a grower to evaluate elevation or slope. Those are obvious to the eye,” said Ben Smith, executive secretary of the Michigan State Horticultural Society. “This project added several extra parameters that are not as easily known by visiting a property. It is also helpful as growers expand outside their local area. I know all the farms close to me very well, but if I go 20 miles away there are a lot of unknowns.”

Fruit mapping

In the late 1970s, the U.S. Department of Agriculture mapped the best planting sites for tart cherries in Northwest Michigan. It was an extensive undertaking, utilizing the latest soil, topography and climate-measuring tools at hand, with the resulting information compiled in a book for growers to consult, Goodwin said.

The tools from four decades ago, however, pale in comparison to the tools available now. Climate, soil and topographic data are much more detailed these days and, being digitized, much more accessible. Remote sensing technologies, such as lidar and digital aerial imagery from aircraft and satellites, provide new data, he said.

Using fuller datasets and more advanced technologies, Goodwin wanted to create a modern site-selection tool for Michigan fruit growers. The state’s viticulture industry, wanting to expand its vinifera acreage but needing better information about where to do that, was particularly excited about the possibilities. When they decided to create the mapping tool, Goodwin and Bunting knew they needed vinifera and climate expertise, so they asked MSU’s Sabbatini and Jeff Andresen, professor of geography, to be consultants.

With funding from the Michigan State Horticultural Society and MSU’s Project GREEEN, the team started creating the online mapping tool in 2019, Goodwin said.

“This award was the largest we have given to a research project, so that should indicate how we valued the work being done,” Smith said. “This will be important to grape growers because, as grower acreage expands, they are always evaluating the suitability of different sites.”

Sabbatini has fielded a lot of inquiries from grape growers over the years, asking if this or that site is good for planting popular vinifera varieties such as Chardonnay or Riesling. Many factors must be weighed when choosing a site — growing degree days, length of growing season, elevation, proximity to water, soil drainage and pH, depth of bedrock, slope, location of frost pockets and sinks that drain cold water, just to name a few — making for difficult decisions. When Goodwin ran the mapping idea by him, it was just what Sabbatini was seeking.

Suitable sites

When the mapping tool concluded that land near Lake Michigan was suitable for growing vinifera, it didn’t surprise Sabbatini — there are already a lot of vinifera grapes there — but the discovery that land near Lake Huron also was suitable did surprise him.

“I thought the lake effect was not strong enough on the other side of the state,” he said. “There’s no history of successful growing of vinifera grapes along Lake Huron, but the possibility is there.”

And though some growers are planting vinifera in Michigan’s interior, the model didn’t locate any excellent sites there. The average mean winter temperature in the middle of the state is too low for vinifera, and such conditions will systematically kill vines without extensive protection systems in place, Sabbatini said.

The mapping tool also accounts for how the land is currently used. If it’s suitable for vinifera but covered by state or national forest, a wetland or an urban setting, the model makes note of that, Sabbatini said.

Overall, the tool shows that there are plenty of good sites for growing vinifera grapes in Michigan, and many of them are not being utilized, Goodwin said.

Similar suitability studies have been done in more temperate wine-growing regions, such as South Africa and California, but this is the first time such a detailed study has been done in a colder-climate growing region such as Michigan, Bunting said.

The model’s next iterations will provide cultivar-specific information and will measure the effects of climate change over time. If the model tells users the site might be more prone to spring frosts a decade from now or has a higher chance of precipitation in the future, that might affect the decision-making process, Sabbatini said.

The project team submitted a proposal to USDA to expand the mapping tool into apples and cherries, and also to expand its use beyond Michigan. The ultimate goal is for a grower anywhere in the country to visit a website, look up a plot of land and be told almost instantaneously how suitable, based on climate and soil factors, it is for the crop in question, Bunting said. •

—by Matt Milkovich

Editor’s note: The caption in this story was updated to note data was still being collected at the time the story was printed, and the map should not be considered definitive.

Very good article on interesting research.

The application has since been updated to include nearly the entire lower peninsula of Michigan. We also added a layer representing the frequency of very cold days in the Winter, which impacts Vinifera survival.