Ron Moorse, a foreman from the Bureau of Reclamation, shuts the Roza Irrigation District down the morning of May 11, 2015, to manage drought conditions in the Yakima Valley, Washington. (TJ Mullinax/Good Fruit Grower)

Click here for a link to the complete report

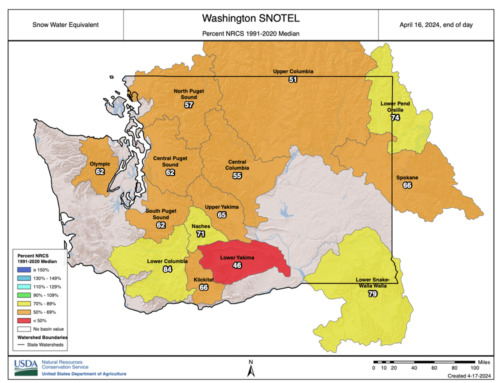

With snowpack levels still sitting above normal for mid-April, Washington growers have little reason to worry about water supplies this season. But two years ago, the worst drought in state history was just getting started and by the end of 2015, it had cost farmers about $700 million.

Record heat and drought conditions were felt across the state that year, but they hit tree fruit growers with junior water rights especially hard. Apple growers in the Yakima River Basin with pro-ratable water rights reported losing several thousand dollars an acre due to lower yields and lower quality fruit, in addition to the cost of operating emergency wells and other mitigation measures.

In a final report the Washington Department of Agriculture puts the economic toll of the drought for agriculture at between $633 million and $773 million – well below the initial predictions that the drought could cost $1.2 billion without mitigation efforts. But it’s also well above the $85 million loss the agency reported in its preliminary assessment in 2016, before significant portions of the analysis were completed.

The most severely impacted sectors included blueberry and raspberry growers in Skagit and Whatcom counties, hay growers with rationed water rights in the Kittitas Valley and tree fruit, wine grape and hop growers in the Yakima Valley with rationed water rights.

The Roza Irrigation District, which received about half its normal water allocation, covers 72,000 acres of mostly high-value specialty crops in the Yakima Valley. There, apple growers reported an average loss of $3,437 an acre and cherry growers lost an average of $1,333 an acre due to reduced yield and quality. Wine grape growers fared slightly better, with losses of about $818 an acre reported. Those losses don’t include the cost of operating emergency drought wells that many relied upon in 2015, which can run between $25,000 and $85,000 per well, depending on maintenance costs.

In Northwest Washington, blueberry growers reportedly lost $7.7 million and raspberry growers lost $13.9 million.

And across the state, reductions in yield resulted in $72 million in losses for apple and pear growers, not including those with junior water rights in the Yakima Valley. And the hot, early spring cost cherry growers $39 million, due to lower quality cherries.

During 2015, the drought energized calls for investing in more water supply security around the state, particularly in the Yakima Basin. But of course, those solutions come with significant price tags — for state taxpayers, irrigation districts and individual growers — and the only way to know if the investment is worth it is to calculate the costs of going without.

Growers across the country are facing similar questions. Last summer’s record-setting drought in Western New York resulted in 50 percent losses for fruit growers who rely on rainfall, according to a recent survey by the Cornell Institute for Climate Smart Solutions. Growers with access to irrigation still lost about 10 percent of their crop, due to insufficient irrigation capacity in terms of equipment and water access.

How will these recent losses affect growers’ needs and willingness to invest in irrigation or on-farm efficiencies? How will the losses change how growers view replanting or diversifying? What is more water worth? Good Fruit Grower will cover these issues and more in the months ahead.

– by Kate Prengaman

This entire subject is absurd. Sure 2015 was a low water year. I’m not so sure about the term “drought”. If we had sensible water rights legislation, across the federal and state level, this would NOT be an issue. Water rights are a ridiculous mess. A totally [F*****] up mess. Here’s an excellent example. In a valley , north of a medium sized city in WA state, there are hundreds and hundreds, No, thousands of homeowners, on 1 to 50 acre parcels, with Senior water rights. These senior rights were purchased with their parcel. Then the parcel developed into a sprawling lawn. These McMansion properties have 10-20 acres of private golf course grade lawns. Why do they have senior rights? Grandfather is the word. These homeowners water 24X7 to “look awesome”. In the meantime, growers of food with secondary rights are being shut off, in order to protect these lawns of the rich and famous.

Will the drought affect cherry season in 2017.

The water supply outlook is normal in the Pacific Northwest this year, so there are no drought fears for cherries or other crops this year.