The final block of the Mazzoni Farm sent a noticeable stir through the crowd. A razor-thin canopy of big, bright, easy-to-reach Cripps Pink apples awaited harvest on vertical leaders shooting up from horizontal cordons.

“Mind-blowing,” Virginia Tech horticulturist Sherif Sherif called it.

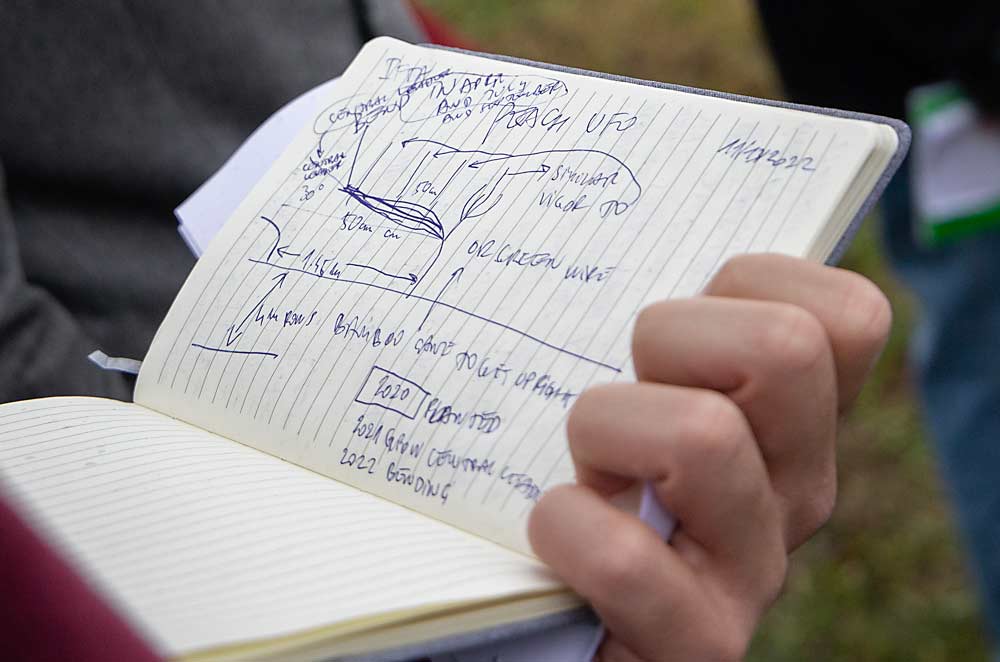

The third-leaf block in rural Ferrara was the most extreme example of multileader training displayed during the International Fruit Tree Association’s tour through the growing regions of Northern Italy. Farm manager Michele Gerin expected about 50 bins per acre from the block, with 90 percent of those apples making premium grade.

But Mazzoni, a diversified agricultural production company in the Po Valley about 30 miles north of Bologna, wasn’t the only place to showcase multileader trees. At every stop, tour-goers gawked at narrow canopies trained with nearly horizontal cordons and upright fruiting wood. Planting densities, vertical spacing and renewal plans all differed, but Italian researchers and commercial growers alike consider multileader training the way to high-yield production, consistent quality and coming automation.

“This is the future of agriculture,” said Franco Micheli of the Edmund Mach Foundation research institute in Trento.

For a week in November, the International Fruit Tree Association, or IFTA, visited growers, researchers and breeders in Italy, one of Europe’s most productive and modern fruit-producing regions. Like the United States, Italy faces labor scarcity, fickle consumers, global competition, increasing government regulations and skyrocketing land prices. Italians consider it imperative to overcome challenges with quality and innovation, not cost savings.

At several stops, IFTA saw multileader blocks presented as an alternative to spindles or two-leader training for their propensity to fill space with fewer trees, spread vigor, enable thinner canopies and make way for the same automation that American growers crave.

In 2018, IFTA participants also saw multileader apple trees on their New Zealand tour. Multileader has caught on in the American Northwest sweet cherry industry under the name Upright Fruiting Offshoot, or UFO, but remains only in the research trial phase for apples.

IFTA reacts

Tour-goers were impressed.

“It was really an amazing experience,” said Sherif of Virginia Tech.

He plans to seek funding to conduct his own trials comparing multileader trees to spindle.

However, he is unsure how many mid-Atlantic growers would adopt a capital-intense system that would require more wires than the spindles they typically employ. He also wonders whether wooden posts would hold the extra pressure with fewer tree trunks in Virginia’s hills.

Italians are known for hilly horticulture as well, but they trellis with prestressed concrete posts. They also use nets and defoliation blowers. Virginians don’t, he said.All those components shift the equation, he said.

Suzanne Bishop of Allan Bros. in Washington’s Yakima Valley, planted a trial of multileader apples in 2021 with 27 different treatments of spacing, numbers of verticals, rootstocks and methods of making multileader fit V-trellis, the preferred architecture of her company and most of the state. Lessons are scarce so far, as the trees fill space, but she favors the idea.

“I think it really makes sense physiologically,” she said.

Trees naturally want to grow up, and a multileader system harnesses that instead of fighting it by training fruiting limbs down. The thin canopy also allows greater efficiency in light use.

She suspects Washington has been slower to adopt multileader apples because Washington is not as limited in agricultural real estate as New Zealand or Italy, so the need has not been as great. Meanwhile, her more seasoned colleagues have invested so much time and energy into perfecting V-trellises, they may not want to start over.

Industry veteran horticulturist Dave Gleason of Domex Superfresh Growers, in Washington, also would like to experiment with more multileader apple systems. The closest he has is an older block on M.26 rootstocks on a V-trellis with 12 leaders, six on each side. However, those were grafted from freestanding Fujis to Autumn Glory. He has never planted a multileader orchard the way the Italians showed.

He’s not sure if all Washington growers, some with less rich soil and shorter seasons, could grow such a big tree in such a short time. Also, as uprights grow thicker and closer together, they cause their own shade and inhibit side breaking, which may mean less fruit.

“I think it has a lot of potential … but you have to see what fits in our growing district,” Gleason said.

Kyle Ardiel, a grower and IFTA board member from Ontario, Canada, agreed. He liked the look of the orchards but had practical doubts about renewal branches causing problems after 10 or 12 years. “Now it’s just a wall of wood,” he said.

Details from Italy

To build multileader trees, Italians grow leaders horizontally or nearly so, almost like a grape cordon, then encourage fruiting branches to break upward. Some people even call them cordon-style trees.

Often, they start with Bibaum trees, a trademarked style of nursery production for two-leader trees, rather than the more common American practice of heading back and splitting young trees in the orchard. They usually use Malling 9 or M.26 rootstocks, but for less vigorous choices or less powerful soil, they sometimes employ only one leader.

Productivity is one of the calling cards.

At the Laimburg Research Centre in South Tyrol, in the foothills of the Alps, fruit physiologist Christian Andergassen has been experimenting with multileader trees on M.9 for six years. In one Fuji block with 6-foot tree spacing, he achieved yields of 257 bins per acre over the course of the first five years. That’s about 100 bins per acre by Year 5, an admirable goal for many Washington growers.

Andergassen stressed the importance of bending the leader a little at a time, starting when it’s just turning green, then visiting the tree often to choose the branches that will become the fruiting uprights. Pick them from the side, or even below, and train them upward, he said. Leaders shooting straight up run the risk of growing too big.

The system requires a lot of baby-sitting early in the process.

“If you want to achieve a result like this, you have to invest in the first two years,” he said. The local extension service, “Beratungsring,” estimated the first two years of cordon-style training require 200 to 300 more hours of training than does spindle-style, he said.

After that, however, the trees become easier to manage. Winter pruning requires about half the number of cuts as two-leader trees the same age, for example.

Just south of there, at the Edmund Mach Foundation research institute in Trento, Micheli has been running multileader trials for 15 years with a combination of permanent and renewal uprights. He favors M.9 and M.26 rootstocks.

He showed visitors where he replaced uprights, which refilled their space in two years because the system allows enough light to reach the cordons. In fact, in some of his blocks, he prefers nonpermanent uprights to keep renewing precocious fruiting wood.

At Mazzoni Farm in Ferrara, Gerin has multileader experiments with a variety of row widths, leader spacing and tree densities, but all of them have thin canopies less than 2 feet thick, while his Bibaum and spindles are well over 3 feet wide.

So far, his favorite is the final block that dropped IFTA jaws — an orchard planted in 2020 with 800 trees per acre on M.9, with up to 10 uprights per tree and almost 10 feet between rows.

He tried limiting uprights to four or six but found it easier to start with more and prune them away than to grow new ones later. But he knows of growers who use the same system with as few as three uprights, depending on their soil and growing season.

He likens tree vigor to an “engine,” and the multiple uprights simply spread out that engine’s horsepower.

Gerin stopped short of advocating a multileader system for everyone, but he insisted it was the only way he could get 90 percent of his fruit to reach premium quality. The two-leaders and spindles, with which he has plenty of experience, maxed out at 75 percent.

In the end, IFTA members pressed him about which system he prefers.

“I will tell you in a couple of years,” he said to a round of laughter.

—by Ross Courtney

good morning, from Italy, I wanted to know if you had a chance to understand more about experts in italian farm machinery. the name of Lorenz Seppi was given you from the Interpoma team. look at http://www.seppi.com

SEPPI M. has a branch in Ohio.

Nice to hear from you, with best regards, Johanna Seppi

Hi Johanna, thanks for checking. I did write a story about Italian farm machinery including Lorenz. It’s here: https://www.goodfruit.com/ifta-in-italy-your-tractor-she-is-bellissima/