John Wise carries out his rainfastness work on grapes and apples at Michigan State University’s Trevor Nichols Research Complex, where he is coordinator of research.

For grape growers in the eastern half of North America, the vine-munching Japanese beetle provides virtually constant pressure from midsummer on. Without an insecticide in place, they attack en masse and can strip a vine of foliage in a few days.

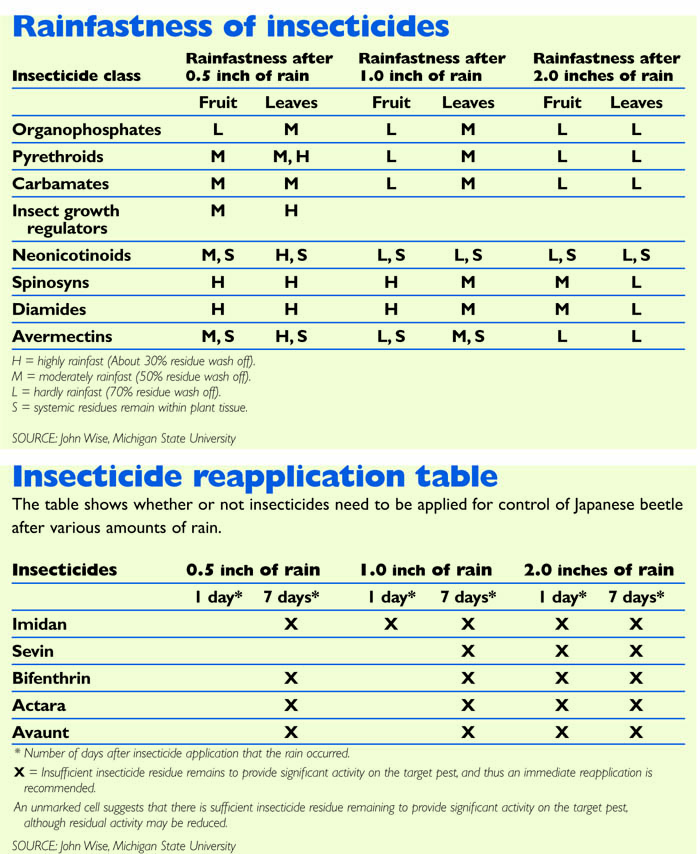

So, how much rainfall is too much? And which insecticides are most rainfast?

Wise, who is also coordinator of the university’s Trevor Nichols Research Complex in Fennville, has been evaluating insecticides for their staying power on grapes. He found that:

- Organophosphate, carbamate, and pyrethroid insecticides were the most toxic to adult Japanese beetles.

- Organophosphate insecticides are the most likely to be washed off by rain, followed by carbamates and pyrethroids.

- Neonicotinoid and oxidiazine insecticides are highly rainfast, but only moderately toxic to Japanese beetle adults.

According to his studies, a two-inch rainfall will remove enough insecticide to make immediate reapplication necessary for all the insecticides he tested: Imidan (an organophosphate), Sevin (a carbamate), Capture/Brigade (the pyrethroid bifenthrin), Actara (a neonicotinoid), and Avaunt (an oxidiazine).

For a recently applied spray (day-old residues), all compounds but Imidan could withstand an inch of rain and would not need to be reapplied immediately. If residues have aged in the field for seven days before the rain, however, then reapplication would be needed for all.

Rainfall of half an inch would not require that any of these be reapplied immediately, but most would need reapplication if the rain occurred after seven days of aging. Sevin, which is particularly effective against Japanese beetles, was washed off by an inch of rain, but enough residue persisted for it to continue to be toxic to the beetles.

The inherent toxicity of the chemical and residual decline by ultraviolet degradation affect whether wash off matters. “The more inherently effective the compound is, the more forgiveness you’ll have in relationship to weather conditions,” Wise said.

After insecticides are applied, a lot of things happen, he said. There is ultraviolet degradation of the chemical; if rain occurs, there is some wash off; and, for some compounds, there is translocation into the plant. “All of these things are factors that influence the subsequent performance of the insecticides,” he said.

Testing was done using a rainfall simulation chamber. After the rainfall, grape leaves were removed and put into cages with adult Japanese beetles to see whether the insects survived after ingesting treated leaves.

Wise presented his findings during a session for grape growers during the Great Lakes Fruit, Vegetable and Farm Market Expo in Grand Rapids, Michigan, in December. He has developed charts that show the impact of rain on insecticide sprays to help growers decide when retreatment is necessary. An Insecticide Rainfall Reapplication Decision Chart is available in the Michigan Fruit Management Guide (MSUE bulletin E-154). The 2011 version costs $25 and can be ordered at http://web2.msue.msu.edu/bulletins/ intro.cfm.

Leave A Comment