A review of the Columbia River Treaty, which the United States and Canada entered in 1964, has British Columbia growers hoping for compensation for the impact it’s had on their industry.

A review of the Columbia River Treaty, which the United States and Canada entered in 1964, has British Columbia growers hoping for compensation for the impact it’s had on their industry.

While the treaty has been effective in managing the Columbia River, harnessing its might for power generation and regulating flows to prevent disastrous flooding along its lower reaches, B.C. growers claim dams Canada built under the treaty also ensured a stable supply of irrigation water that supported the incredible growth of the Washington State apple industry in recent decades.

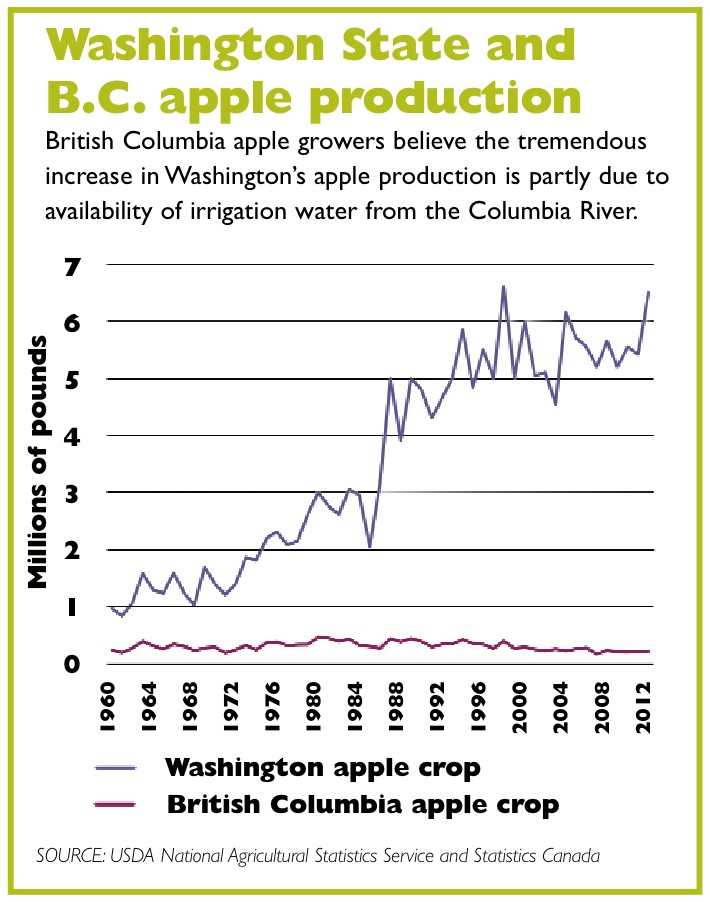

Since completion of the first dam built under the treaty in 1968, apple acreage in the state has risen from 60,000 acres to approximately 150,000 acres today. Production has increased more than sixfold, reaching 6.5 billion pounds in 2012.

The dramatic growth has had international impact.

“Washington has captured all of the growth in the domestic market and taken a small portion of the market away from other growing areas,” observed Dr. Thomas Schotzko and David Granatstein, extension scientists at Washington State University, in a 2004 paper.

It’s no surprise to B.C. growers, now dwarfed by the giant to the south. British Columbia has shifted to newer varieties and more productive plantings, but Washington—where apple production was seven times as great as British Columbia through the 1980s – today produces more than 30 times as many apples as its northern neighbor.

Meanwhile, production in British Columbia has slipped from more than 300 million pounds a year in the late 1960s to 215.5 million pounds in 2012.

“The impact of the increased volumes is unquestioned,” said Glen Lucas, general manager of the B.C. Tree Fruit Growers Association that represents most growers in the province.

Washington has become so productive that many B.C. growers believe the treaty has caused them economic hardship. The state’s output was so overwhelming that growers sought and obtained an antidumping order against Washington State apples in 1989 (the order was rescinded in 2000).

With the Columbia River Treaty under review, fruit growers have joined with the B.C. Vegetable Marketing Commission and the B.C. Potato and Vegetable Growers Association to seek a cut of revenues the province receives under the treaty.

Residents displaced by dam construction and reservoir creation in the Kootenay region received compensation, and in 1995 the province created the Columbia Basin Trust with a $295 million endowment designed to support social, economic, and environmental initiatives in the area.

Growers have suggested an annual allocation of $9.25 million for the competitive disadvantage they face, a fraction of the $200 million to $300 million the province receives from treaty power sales each year.

Tough to prove

But drawing a connection between the treaty, irrigation, and industry growth in Washington, and the effect these have had on growers in British Columbia, is easier said than done.

The treaty doesn’t affect the supply of irrigation water in British Columbia’s Okanagan Valley, for example. While it has helped regulate the flow of water down the Columbia, a stable supply of water for irrigation in Washington wasn’t an immediate guarantee of success. More productive, higher-density plantings with newer varieties also boosted crop volumes.

Washington tree fruit surveys conducted by the National Agricultural Statistics Service show that apple acreage in Washington grew only slightly from 160,980 acres to 167,489 acres between 1986 and 2011. Increased plantings in the Columbia Basin were offset by a significant reduction in acreage in the Wenatchee district, which also draws water from the Columbia.

Lucas acknowledged that water hasn’t been the only factor at play, but the timing of growth points to the treaty’s significance.

“There may be other competitive factors at play—I’m sure other things have changed in 50 years,” he said. “

The scenario is repeating itself, Lucas believes, as the Washington State cherry crop surges (often with new varieties developed in British Columbia).

“We’ve seen this happen with apples over the past 50 years, we’re now seeing it with cherries—this incredible expansion. And a lot of it is due to the availability of water,” he said. “And how is that linked to the Columbia River Treaty? Our task is to do that investigation and provide that information.”

Washington tree fruit surveys show that the state’s cherry acreage increased from 13,925 to 38,115 acres between 1986 and 2011. Two-thirds of the total acreage is in the Wenatchee and Columbia Basin districts.

The less change to the treaty, the better, said Tom Myrum, executive director of the Washington State Water Resources Association, which represents the state’s 35 irrigation districts.

Yes, water’s key

“In general, the irrigation districts would like to keep operations as they are. It’s much easier to deal with the known compared with the unknown,” he said.

Without renewal of the treaty’s flood control provisions, dams and reservoirs in Washington State would likely bear a greater responsibility for flood control, Myrum explained. The river would

carry the same amount of water, but management would have a different purpose. Power generation and flood control would take priority, while irrigation systems would be secondary.

“What does that mean to the operation of the reservoirs that we have for so long been operating for the benefit of irrigation?” Myrum asked. “The best we can do is theorize. What we want is security of water delivery on an annual basis. We don’t want the unknown.”

All amounts quoted are in Canadian dollars, which are currently nearly equivalent with U.S. currency.

What is the Columbia River Treaty?

A model of international cooperation, the Columbia River Treaty between the United States and Canada aimed to boost power-generating capacity along the river and improve flood control.

The treaty authorized construction of four dams on the upper Columbia River system, including three in British Columbia and a fourth on the Kootenai River in Montana. In exchange for flood control in the United States, Canada received a one-time payment of $64 million (at the time, an amount equivalent to half the cost of flood damages the United States expected to avoid under the treaty).

British Columbia also received an annual allocation of hydropower equivalent to half the estimated increase in U.S. generating capacity, thanks to water released from the dams in Canada.

This year, the amount is approximately 4,275 gigawatt hours—enough to power about 1.25 million homes.

The treaty has no end date, but either party has the right to terminate its provisions after 60 years, with at least 10 years’ advance notice. Termination would leave British Columbia without its power allocation.

Should the treaty remain in place post-2024, a new agreement must be hammered out regarding compensation for flood control and water diversion provided by dams in Canada.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and Bonneville Power Administration is overseeing the U.S. review of the treaty, and rolled out a second report at a series of public open houses this spring.

B.C.’s Ministry of Energy and Mines is overseeing the review in Canada. Various stakeholders, including the agriculture sector, sit on the ministry’s review panel. The results of public consultations to date will be released in June.

Leave A Comment