Intuition might tell blueberry growers to place as many honey bees as close to their crop as possible.

But early results from a nationwide blueberry pollination research project suggest more nuance.

Dispersing colonies along the field edge and stocking more hives do not increase bee visits, yields or berry weight. Meanwhile, landscape structure, hive health, plant physiology and horticultural practices do matter.

“Pollination is important, but it’s only one piece of the puzzle,” said Lisa Wasko DeVetter, a small fruits specialist at Washington State University’s Mount Vernon research center.

Data so far from a wide-ranging project at four universities may debunk a few myths regarding blueberry pollination, which scientists believe has been understudied given the fruit’s rapid surge in production, acreage and value throughout the world.

Researchers from Washington State University, Oregon State University, Michigan State University and the University of Florida are participating in the project, funded by a $2 million grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Specialty Crop Research Initiative.

Hive density

Take hive density. Growers are tempted to stock as many hives as they can afford, figuring the more bees, the better. That’s only true up to a certain point, because bees don’t really care about property lines, DeVetter said.

In 2021 and 2022, DeVetter’s colleagues in Michigan and Florida compared bee visits and berry weights from fields with densities ranging from two to six hives per acre. Bee visits and berry weight — a yield metric — were not affected by increasing hives per acre.

However, a different study done in Washington showed bee visitation is influenced by hive density in an overall landscape within 1,000 meters beyond the borders of a field.

That means neighbors matter. Some growers in Whatcom County, one of Washington’s top producing regions, already stock their own fields while taking into consideration their neighbors’ hive densities, DeVetter said.

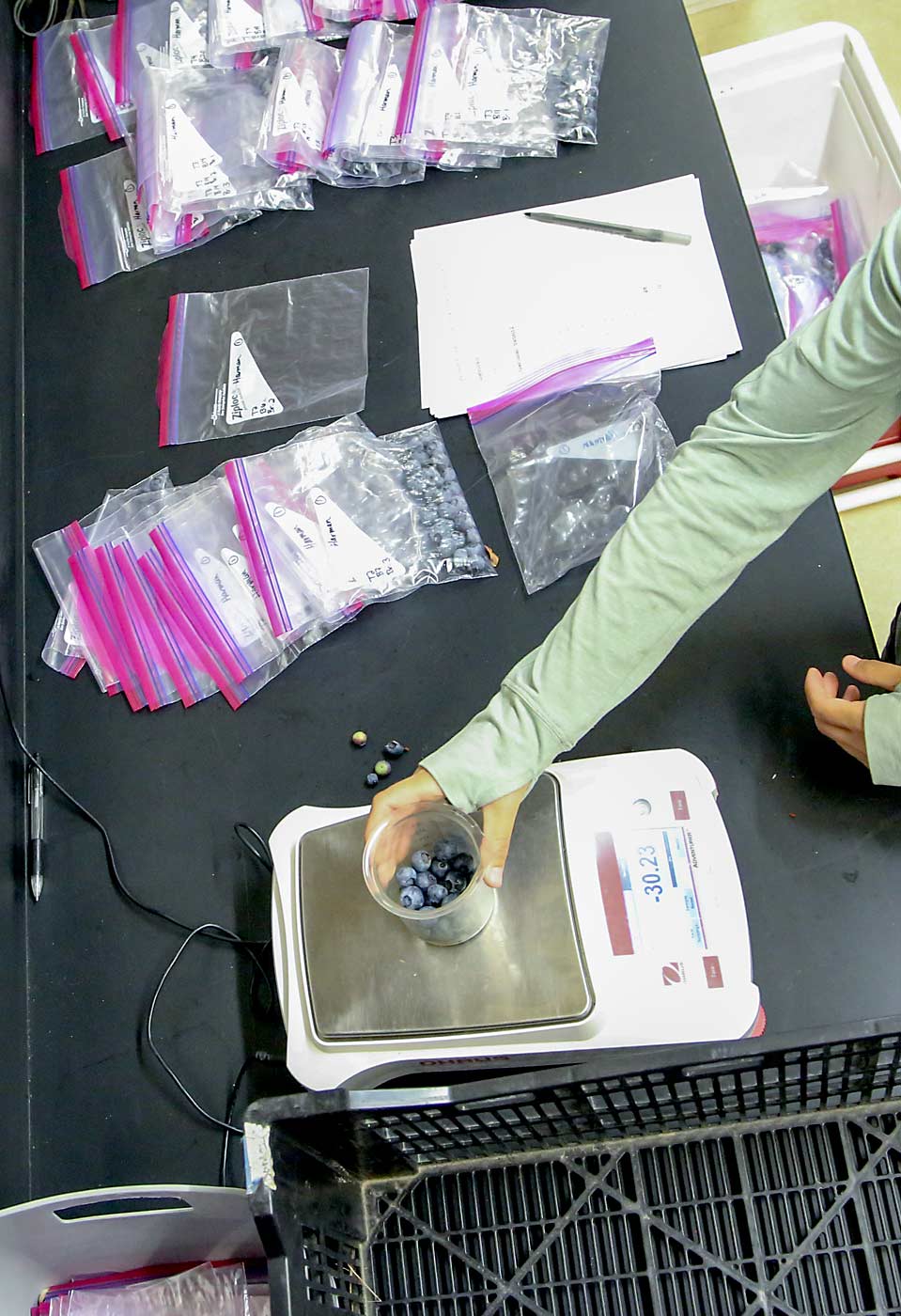

The researchers measured results of the pollination trials by physically walking marked rows and counting how many bees they saw working blooms. They also counted seeds and weighed berries. Heavier berries and greater yields indicate better pollination.

Hive placement

Hive placement within a grower’s operation also makes a difference.

Growers often ask beekeepers to place hives immediately adjacent to their fields, figuring that will make it easier for the bees to spread out and do their work. Honey bees tend to have a low attraction to blueberries, compared to other blossoms, DeVetter said.

However, that practice may just cause unnecessary headaches for the beekeeper, already expected to trudge through muddy conditions at night under intense deadlines.

Turns out, clustering hives in a few locations away from field edges works at least as well, if not better, said Kayla Brouwer, a graduate student at WSU-Mount Vernon who helped with the research. In trials in 2021 and 2022 in Michigan, Washington and Oregon, researchers counted at least as many bee visits from hives clumped together, compared to those stretched along field edges. In Washington, under optimal pollination conditions, bee visits actually increased with clustering, Brouwer said.

Berry weights from those fields were similar, too, researchers said.

The reason is uncertain, but theories include the possibilities that adjacent hives compete and forage harder or radiate heat for each other and fly earlier.

Pollinator habitat and pesticides

In another result, the researchers learned that Northwest blueberry growers can boost wild pollinator populations with seminatural habitats, such as a strip of flowers, a hedge row of trees or areas of forest and grasses, near their fields. Earlier studies from Michigan and Florida have shown the same.

Bumble bees, for example, are an effective blueberry pollinator. Compared to honey bees, bumble bees and other alternative pollinators often fly in cooler conditions, such as those in drizzly Western Washington and Western Oregon. Sometimes blueberry growers struggle even to obtain honey bees at all because beekeepers, who travel the nation with their colonies, don’t always want to stop in blueberry country.

Researchers also are measuring how colony placement affects pesticide exposure. That work is still underway.

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment