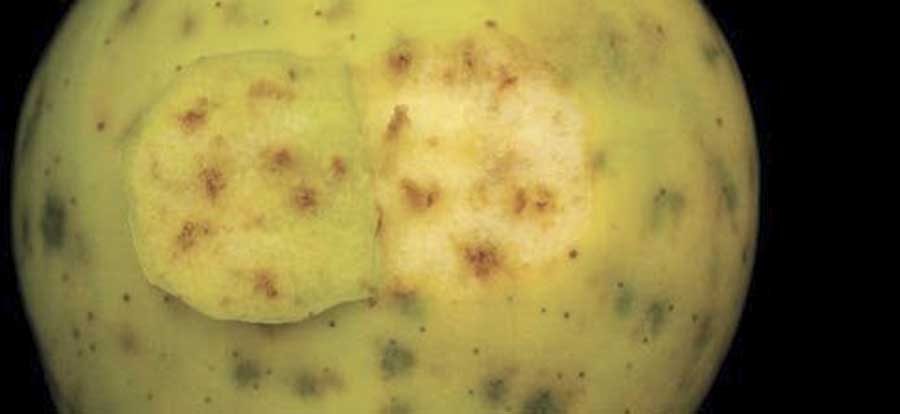

Symptoms of bitter pit include dark sunken pits on the surface of the fruit and corky brown tissue. (Good Fruit Grower file photo)

Bitter pit, a postharvest disorder of apples, is often thought to be linked to fruit size, with larger fruit being more susceptible.

But Tim Smith, Washington State University Extension agent in north central Washington, says just about everything in the orchard can influence the amount of bitter pit, with some factors being more important than others.

Bitter pit is a calcium-related disorder, but large fruit doesn’t necessarily have lower calcium levels. Speaking at the Lake Chelan Horticultural Day this winter, Smith said research by Dr. F.D. Broom, horticulturist with HortResearch in New Zealand, has shown that there is no relationship between fruit size and the calcium levels, so fruit size is not the only factor making the fruit prone to bitter pit.

Leaf-to-fruit ratio

One factor that does make the fruit susceptible is the leaf-to-fruit ratio, with bitter pit tending to be worse on lightly cropped trees. There is a strong relationship between the number of leaves and the amount of calcium in the fruit.

An apple acts as a reservoir of water. Every day, between 10 a.m. and noon, water starts to leave the fruit and goes to the leaves. In the late afternoon, the water reverses and goes back in. The more vigorous the canopy, and the more water that leaves the fruit, the more likely it is that the calcium will be lost from the fruit and not return. This can result in low calcium in the fruit and potential bitter pit problems.

A high leaf-to-fruit ratio can result from a small crop. And a small crop can be the result of a boron deficiency, poor pollination, or a lack of compatible pollen.

Smith said research has shown that the pollen source can greatly affect the amount of pollination and how quickly it happens. Manchurian crab, for example, can be a good pollinizer for one variety, but not for another. Poor pollination can also be attributed to a lack of bee activity resulting from rainy, cold, or windy weather during bloom, sprays that are toxic to bees, or colony collapse disorder.

A high leaf-to-fruit ratio can also result from excessive vigor in the tree, good soil, excessive nitrogen, heavy pruning, a vigorous rootstock, overthinning, or overirrigating.

Roots

Sometimes, insufficient calcium in the fruit results from a lack of calcium traveling up the tree from the roots through the vascular system. Calcium is transported to the fruit through the xylem, which serves as the connection between the fruit and the ground. The transport of calcium can be disrupted when there is incompatibility of the scion and rootstock, or when winter damage disrupts the xylem, Smith said.

Poor uptake of calcium by the roots can also be caused by dry soil, low soil calcium, a low calcium-to-magnesium ratio, a large amount of potassium fertilizer, heavy weed or grass growth, or competition between tree roots in a high-density planting.

Poor root function can also reduce calcium uptake and that can be caused by salinity in the soil, acidic soil, inadequate potassium, low phosphorus, compaction, low oxygen, cold conditions, waterlogging, root disease, replant disease, or nematodes.

Xylem

The transport of calcium up through the xylem stops as the fruit approach maturity and begin to form the abscission layer in preparation for falling off the tree. That’s why late foliar calcium sprays are more important than earlier sprays, which are just adding to the supply coming from the soil, Smith said. The cultivars that are most prone to bitter pit lose their connection with the xylem earlier than unsusceptible varieties, Smith explained. In Braeburn, the xylem connection breaks down a lot earlier than it does with Granny Smith.

There’s also a relationship between the number of seeds in the fruit and the likelihood that it will develop bitter pit, Broom’s research in New Zealand shows. This is because the more seeds the fruit has in it, the higher the calcium relative to other fruit on the tree. Also, the greater the number of seeds, the longer the fruit might maintain an adequate connection to the tree, Smith theorizes.

Tree age

The age of the tree is important. Young trees are likely to have a lot of vigorous growth and a high leaf-to-fruit ratio. The grower will need to make sure the trees receive enough calcium until they mature and come more into balance.

Smith concluded that just about everything in the orchard can have an influence on bitter pit, but adding calcium to the soil is unlikely to help. Calcium carbonate is a good thing to add to the soil to raise the pH level, he said, but it won’t have a direct impact on bitter pit. Usually, the problem is not a lack of calcium in the soil. The risk of bitter pit can be reduced by foliar applications of calcium chloride, which place the calcium directly on the skin of the fruit, where it’s needed.

I very much appreciate the information provided on bitter pit.