Selling CandyCots was never the problem. Nor were prices.

For years, the sweet, succulent California apricots sold for well above the cost of production.

“We were doing well with margins there,” said Chris Britton, one of the partners of CandyCot, the Modesto, California, business that developed and marketed the once popular variety. But climate changes and escalating labor costs pushed the growers out of the stone fruit business five years ago. Today, almonds grow right next to signs bearing images of the peaches and apples that used to grow there.

“I have no plans to plant any more stone fruit,” Britton said.

When Good Fruit Grower asked him about the future, he said, “I’m growing almonds. I think that speaks for itself.”

The same pressures are mounting on other growers. Stone fruit in California, far and away the largest producing state, sits at a “precipice,” said Ian LeMay, president of the California Fresh Fruit Association.

California grows about 80 percent of the nation’s stone fruit — 70 percent of peaches, 95 percent of plums and 99 percent of nectarines. Most of them are grown near Fresno, near the association’s office in the southern half of California’s Central Valley.

Like other fruit industries, stone fruit has spent the past 20 years or so consolidating into fewer, larger companies. The 2011 dissolution of the California Tree Fruit Agreement, a federal marketing order, hastened the trend for a while, LeMay said, though overall production, acreage and number of producers had largely remained steady over the past seven years.

In fact, one of the association members recently planted thousands of new acres, while others have modernized packing lines.

“Stone fruit is not going away … it’s just trying to find that sweet spot where you can sustain the business model,” LeMay said.

However, mandated overtime for agricultural workers, the highest minimum wage in the country, continuing port backups and shifting consumer tastes have altered the trajectory, he said. Over the past two years, a few producers have resumed consolidating, or just left the business altogether. More could follow, he said.

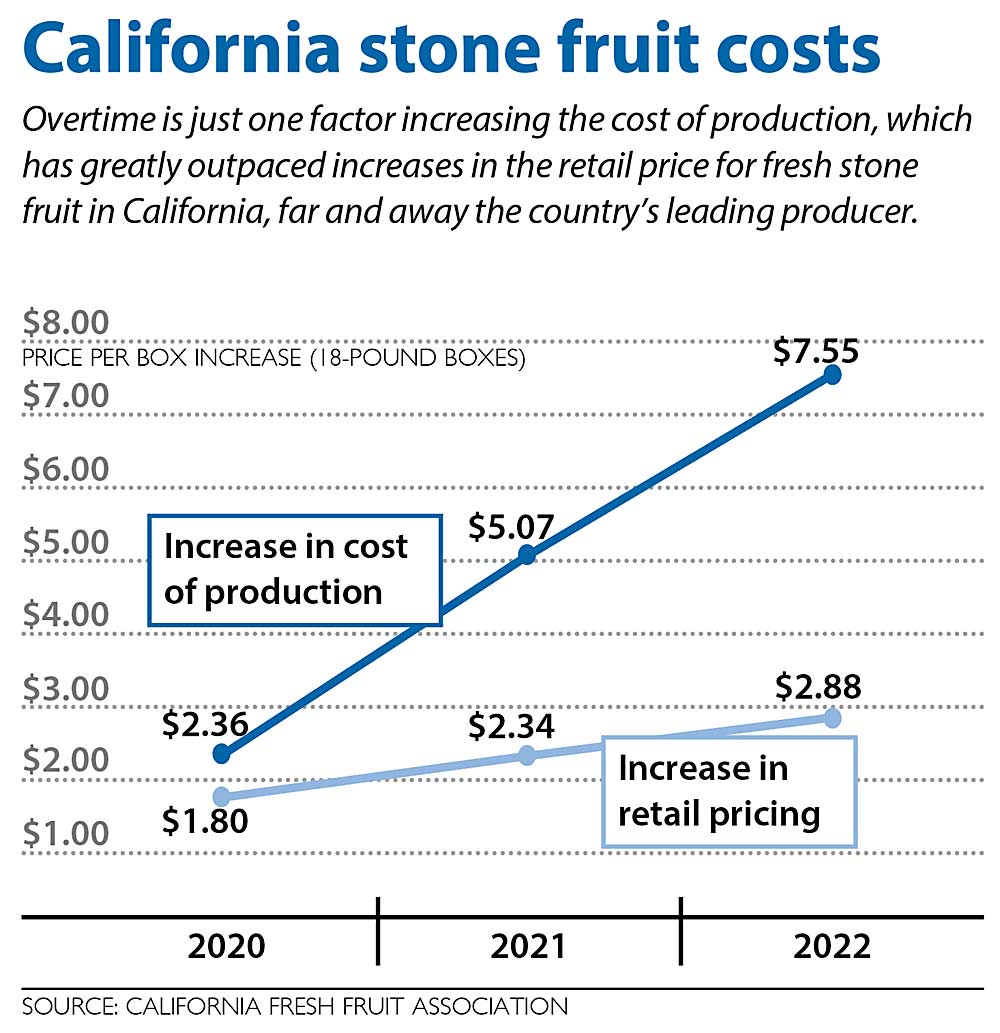

Since 2020, the cost of producing an 18-pound box of fresh stone fruit has more than tripled, though retail prices have increased by only 60 percent, according to the fresh fruit association.

“It’s going to make growers have to make decisions,” he said.

On the farm

CandyCot is a relatively small example with a relatively well-known name.

Modesto, Lodi and other communities near Sacramento comprise the northern fringe of the Central Valley’s stone fruit region. The areas were better known for canning peaches, which have been in decline, along with all canned produce.

Labor-efficient almonds and pistachios have been moving into the area, attracted to its healthier water supply as compared to the drought-stressed southern neighbors of Fresno, Kingsburg and Visalia.

Britton and his farming partner, John Driver, started CandyCot LLC in 2010, planting about 150 acres of the variety bred by Driver, who has traveled the world in search of the best stone fruit DNA. CandyCot came from a region near the Central Asian mountains where the apple first evolved.

The flavor was sweet, complex and exciting. For a while, the cultivar sold itself. The New York Times wrote it up in 2008.

“It was something that was a lot of fun,” Britton said during an August interview with Good Fruit Grower. “Everybody loved them.”

However, the hand labor costs became prohibitive, Britton said.

Meanwhile, the cultivar cracked with the region’s late spring rains and many years lacked enough chill hours to set a crop that met the company’s presold contracts. So, rather than continue to risk their reputation, they pulled out the trees in 2017.

Since then, the partners also sold off some of their apple orchards, but they custom-manage apples for another owner. Britton is a former chair of the U.S. Apple Association. He also whittled down his 600 acres of canning peaches to 30, but he said he’s still hopeful about cherries, a crop that is relatively attractive to labor.

Driver, meanwhile, still breeds under the business name CandyCot and consults in the micropropagation, tissue culture arena.

But the partners won’t plant any more stone fruit.

“We won’t plant any because we don’t want to go there,” Driver said. “The environment is just not conducive for growing those types of high-touch crops here in California.”

—by Ross Courtney and TJ Mullinax

Leave A Comment