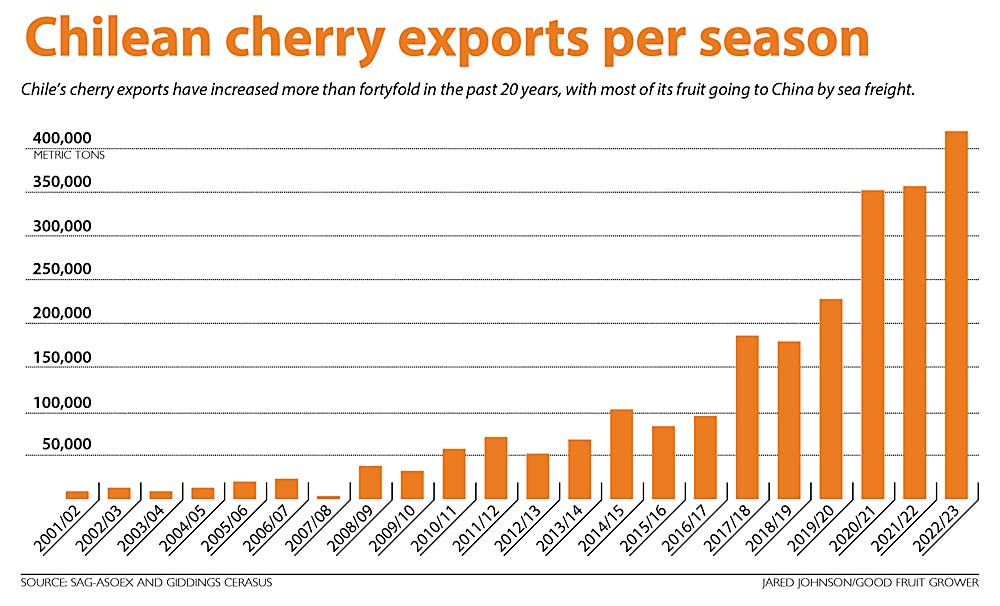

Saying the Chilean cherry industry is growing is an understatement.

Sweet cherry exports from the South American country have shot up more than fortyfold in the past 20 years. The country represents 95 percent of the Southern Hemisphere’s production. And by 2026, Chile expects to surpass 800,000 metric tons of cherries; if true, that will be more than four times what the Northwest cherry-producing states consider a normal crop.

Those are the stats Ramón Arrau, president and CEO of Giddings Cerasus, shared with growers in January in Yakima, Washington. He spoke at the 80th annual Cherry Institute, the annual meeting of the Northwest Cherry Growers, a collective marketing group based in Yakima.

Arrau also stressed that his country’s industry desperately needs to diversify and is doing so in the United States.

“The main question that everybody keeps asking is … when will China put some pressure on you with the prices?” he said.

Chile exports about 85 percent of its fresh cherries, according to Arrau and U.S. Department of Agriculture statistics. Of those exports, more than 88 percent go to China. That’s a lot of eggs in one basket, Arrau said during the conference and in a follow-up conversation with Good Fruit Grower.

Giddings Cerasus, the No. 6 cherry producer in Chile, normally sends about 70 percent of its cherries to China. Almost all of them are shipped by ocean freighter, rather than by airplane like U.S. cherries.

Chile’s tree fruit industry already has faced some struggles shipping to China, with logistical supply chain snafus due to COVID, Arrau said.

To counteract the risk, about six years ago the country decided to diversify breeding — Lapins currently make up 38 percent of the crop, Santina 29 percent, Regina 11, Bing 6 and Sweetheart 4 — and reach out to other markets.

Grower profits from Chinese customers have led to the extreme growth, so convincing them of the need to consider other markets may take some salesmanship, he said.

Giddings Cerasus has been operating for about five years in the United States, contracting cherries from Washington under the horticultural advisement of their own field representatives. They pack under a joint venture agreement with River Valley Fruit of Grandview.

Giddings Cerasus has the same goal for its U.S. cherries — 70 percent export to China. However, in 2022, it was only 45 percent due to lack of volume caused by poor spring pollination weather.

Giddings Cerasus plans to start building a packing facility in Selah this year or in 2024, probably starting with 24 Unitec sorting lines, Arrau said. The company’s goal is to produce fresh cherries year-round and “close the windows in the gaps in between Chilean production and American production,” he said. They plan to export the U.S.-grown cherries by ship, as well, he said.

Giddings has already started the move, purchasing cherries at high prices straight from Northwest growers, said B.J. Thurlby, president of Northwest Cherries. Representatives also have been showing virtual tours of the proposed facility at produce trade shows around the globe, such as the annual Produce Marketing Association Fresh Summit.

“The growers need to know about it; that it’s happening and there’s another packer out there, that they’re serious about getting involved,” Thurlby said.

Some Northwest cherry producers own orchards and production facilities in Chile, too.

For the sake of the global industry, Thurlby hopes Chile’s diversification efforts aren’t coming too late.

“I think they should have spent some more time looking at other markets as more and more acreage came into production,” Thurlby said.

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment