Mother Nature may have overcorrected.

After a scorching summer 2021, an unusually cold April 2022 covered trees with snow and sent growers scrambling to protect blossoms from cold damage, while wheeling and dealing for limited supplies of propane.

The biggest problem, however, was the string of snowy, rainy and windy days that kept bees from flying.

“We’ve had cold damage before; we’ve had frost nights before,” said Jason Matson of Matson Fruit in Selah, Washington. In fact, his crews fired up wind machines and heaters less often this year than last year, he said. “But a week of 32-degree highs or whatever it was? We’ve never had that. That’s the problem.”

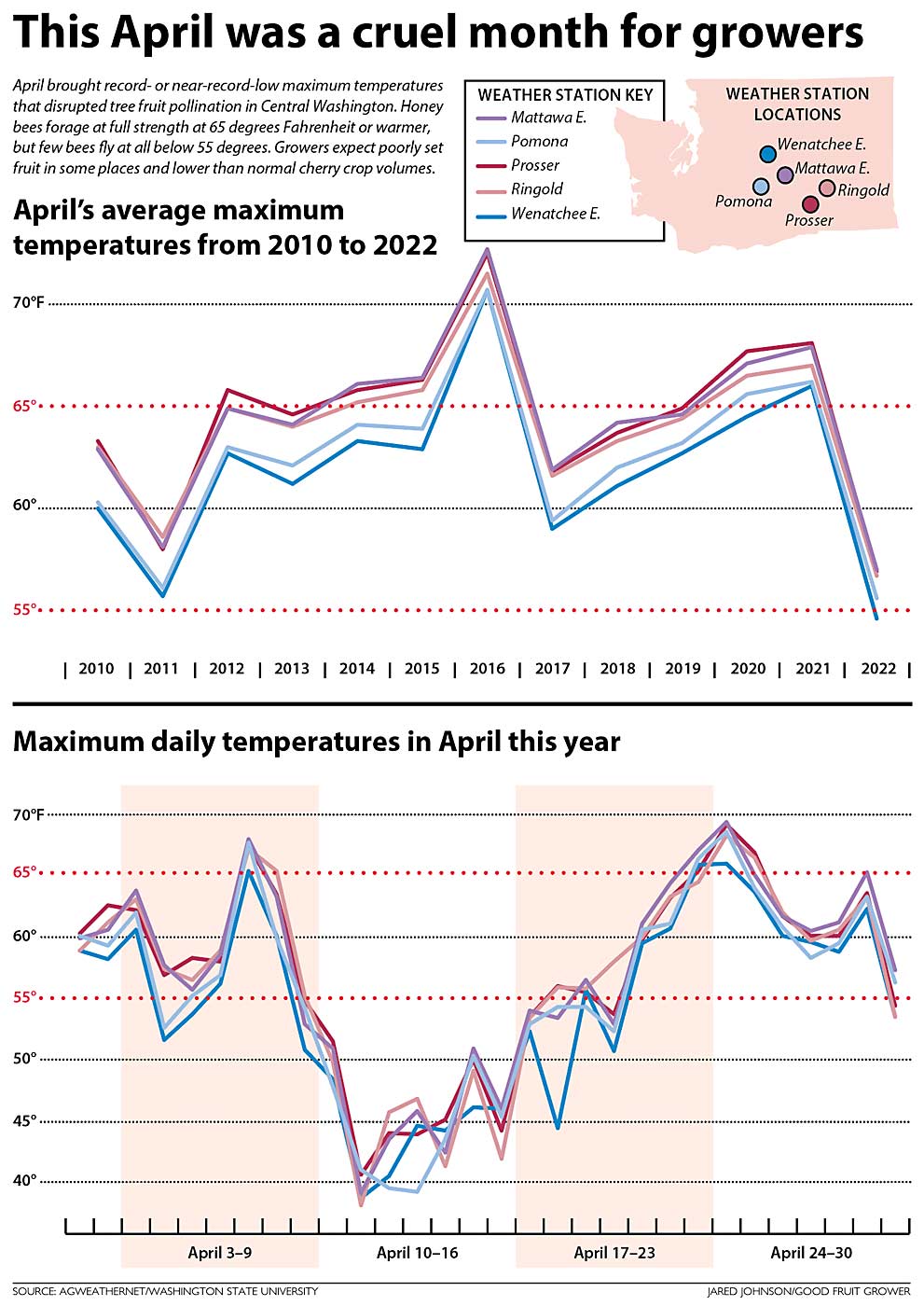

Matson exaggerated only a little. Several locations in Central Washington set record-low maximum temperatures for April, and highs stayed below normal for nearly two weeks in the middle of the month, according to AgWeatherNet, Washington State University’s system of weather stations. WSU’s Pomona weather station, near Matson’s farm, registered a high of 39.2 degrees Fahrenheit on April 12. The previous coolest April high since 2009 was 48.1 degrees. Stations near Wenatchee, the Yakima Valley and Mattawa also set new records for cold maximums in April.

For a stretch of 12 days at the Pomona station, daytime highs ranged from 39 degrees to 54 degrees. Few honey bees fly below 55 degrees, and they don’t forage at full strength until the thermometer reaches 65, according to WSU’s online tree fruit literature. Growers near Pasco had a string of eight sub-55 days, while Prosser and Mattawa had 10.

Then, the weather really didn’t warm up much the rest of the month, Matson said. Several cherry and apple blocks, depending on location, set so poorly the company may not try to harvest them.

“It’s not looking good,” he said.

A 39-year veteran crop advisor echoed Matson.

“There’s probably much more damage from lack of bee activity than from actual frost damage,” said Greg Pickel, business development manager for G.S. Long Co. of Yakima, Washington.

Cherries will see a reduced volume, he said. Apples are less certain, he said, but they started the season with a lighter bloom due to the 2021 heat wave. The cool April only made matters worse.

Cherry volume will definitely be short, said B.J. Thurlby, president of Northwest Cherry Growers.

“We know it’s significantly reduced,” he said.

In mid-May, the Yakima, Washington, group called for a 136,800-ton harvest at its annual five-state meeting. If the figure holds, it would be the smallest since 2008, when there was a third less acreage in production, and over 30 percent smaller than the heat-scorched 2021 crop of 203,000 tons.

Time will tell more. Changes to the estimate are common as the growing season progresses. One thing was clear, though: Some cherries were pollinated before and after the cold spell, which could create awkward size profiles later on, Thurlby said.

Bloom timing

Bloom timing and weather varies by region and variety, of course, but generally, cherries fared worse than apples or pears, said Matt Whiting, a fruit physiology professor at Washington State University’s Prosser campus. Cherries bloom earlier and had progressed in development just as the weather forced bees to huddle in their hives. Some fruit probably did not set, he said.

“This is kind of a scary prospect,” he said.

Whiting suggested growers in that situation adjust their irrigation and pruning strategies in the coming months. Summer pruning will calm down trees that respond to the lack of fruit with more vigor.

Also, trees may react to the absence of a crop this year by creating more flowers per bud next year; more aggressive winter pruning can mitigate this. Left on their own, cherry trees can go slightly biennial, though not as severely as apples.

Apple growers responded to the pollination concerns by holding off on bloom thinning, even though it may mean more fruit thinning later. By early May, Matson Fruit had not applied any lime sulfur or chemical thinners, Matson said.

Denny Hayden, a cherry and apple grower north of Pasco, a relatively warm, early site near the Columbia River, skipped his first round of lime sulfur on his organic Honeycrisp, Fuji and Gala apples. But weather improved some in his area by the end of the month, and bees resumed activity. So, he made his second and third applications, he said.

As for cherries, Hayden expects a reduced crop, but he may have gotten lucky on some varieties. Early in April, as Chelans and Bings neared full bloom, bees put in a few solid days of work early in the month, and his crews finished their usual dry pollen applications before the cold weather struck. Later-blooming varieties, such as Early Robins and Skeenas, needed extra applications of growth regulators to extend ovule longevity, he said.

Overall, he’s expecting some reduction in cherry volume but a relatively normal apple set.

Growers to the south, in the Columbia Gorge region, likewise eyed pollination with more concern than cold damage.

“It will be a strange year,” said Devon Wade, a cherry grower in The Dalles, Oregon.

Alan Reitz, a field representative for Mount Adams Fruit, estimated at least a 60 percent cherry crop in The Dalles and in Dallesport, Washington. Young trees seemed to set better than mature trees, which is not unusual, he said.

As for pears, trees in the middle of the Hood River Valley near the Odell, Oregon, packing facilities face some uncertainty, Reitz said. They were in a critical bloom period during the depths of the mid-April cold spell. Orchards at lower elevations near the Columbia River seem to have set well, while blooms in the upper valley around Parkdale were still closed in mid-April. Many growers there had yet to place bee colonies.

“Still think we have a potential for a good crop of pears, especially in the Lower Valley,” Reitz said. •

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment