American fruit growers are land-rich by Italian standards, Dorigoni says. In Italy, orchard land has been in use for centuries and is continually renewed to obtain higher yields while relying on the family for labor. Inset: Alberto Dorigoni explains cuts made for the window-pruning approach.

PHOTOS BY MELISSA HANSEN

Dr. Alberto Dorigoni is studying this approach at the Istituto Agrario Di San Michele All’Adige in Italy’s South Tyrol province. He described his work during the International Fruit Tree Association conference in Boston in February.

Think of window pruning as a tool to make several openings in a fruiting wall. The outer, smooth face of the wall is formed by a sicklebar hedger positioned about two away from the tree trunk, and slanted slightly inward toward the tree, making the top of the tree thinner than the bottom.

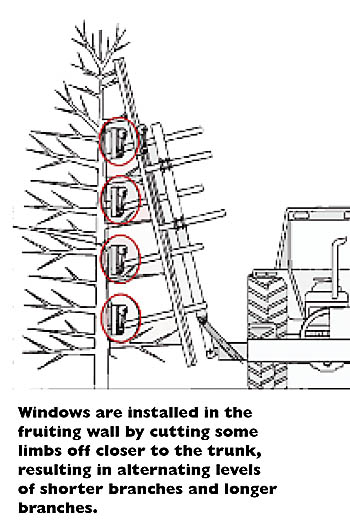

Windows are “installed” in this wall by cutting some limbs off closer to the trunk, resulting in alternating levels of shorter branches and longer branches from the bottom to the top of the tree. This creates windows that let light into the center of the trees.

One company in Italy, called Fa-MA, is building the F.E.M (Fondazione E. Mach), a patented machine that makes these windows. Four cutting units, each 15 inches long, run inside the tree canopy while the sicklebar outside does the hedging. There are seven such machines in use in Italy, working in apples, peaches, pears, and plums, Dorigoni said. Demonstration trials are in progress in other countries.

“Traditional mechanical pruning shapes a fruit wall that still needs about 40 to 70 hours per hectare (16 to 28 hours per acre) of winter pruning to get rid of excessive wood inside the tree,” Dorigoni said. “The window-pruning machine’s goal is to mimic hand pruning and trigger a cycle of shoots. The resulting shape looks more similar to a hand-pruned spindle tree than to a fruit wall.”

The number of interior cutting units can range from one or two to three or four, and the distance from the trunk can vary from 4 to 20 inches. The angle of both the outside and inside cutting bars can be changed.

The window-pruning machine can operate either in winter or as a postharvest pruning treatment. When the inside cutting units are removed, it becomes a traditional pruning machine.

By changing the height of the windows over the years, so that what is left long one year is cut short in another, it is possible to induce a cycle of new shoots.

Reduce labor

Dorigoni began working in the last decade on ways to reduce the amount of labor expended in orchards. Many Italian orchards are small, family-owned operations, and growers need to make intense use of limited land without using much hired labor. Some land has been in orchards for more than 600 years. Dorigoni began working on mechanization and ways to speed up thinning and pruning.

“I realized that any form of mechanization or simplification was more suitable to the fruit wall system than to the long pruning system,” he said.

With long pruning, it is easier to balance tree vigor. Dorigoni is trying to find this balance by using both mechanical pruning and multistem (multitrunk) systems to spread vigor over more upright axes coming from the same base.

“It turned out that both techniques had powerful impact and could be used to make an ordinary orchard suitable to further mechanization,” he said. “In this respect, mechanical pruning is much more than just a time-saving technique: it paves the way to further benefits in a cause-effect development.”

The window-pruning machine was an evolution of the traditional mechanical pruning done mostly to speed up follow-up hand pruning in winter.

The hedger-created fruiting wall is very amenable to the use of platforms and to mechanical blossom thinning. Dorigoni uses the Darwin string thinner on apples.

In Europe, the movement is away from chemicals to more environmentally benign methods. Mechanical thinning might be critical since the Europeans can no longer use the chemical thinner carbaryl. The narrow fruiting wall is also more suited to mechanical weed control. Mechanical pruning eliminates chemicals for controlling shoot elongation, while promoting flower bud formation and improving fruit size and color.

“The first trials with window pruning without hand correction look good both in terms of crop and vegetation in the following year,” he said, adding that the idea is to use window pruning as an aid to, not a full replacement of, hand pruning.

“I personally think that U.S. fruit industry somehow suffers from what I call the ‘paradox of cheap land,’” he said. “I mean, it is great to have a lot of territory available. But it does not help making rational use of it, while in contrast in South Tyrol, where land is very expensive, growers are forced to use it more efficiently without even realizing it.”

Rootstocks

Dorigoni and Cornell’s Dr. Terence Robinson have been watching each other’s work in recent years. Robinson is looking closely at fruiting walls created by mechanical pruning, and Dorigoni is looking at Cornell’s rootstocks.

“Terence and his group launched very interesting rootstocks, which is really something we lack in Europe,” Dorigoni said. “These stocks have high potential to my knowledge for forming traditional spindle as well as multistem trees.”

Leave A Comment