Meteorologists and growers agree that last summer’s heat wave was bad, unusually bad. But forecasters warn that, in the future, the record-setting temperatures of 2021 may not be a one-off.

“It’s something that we’re going to see multiple times in everybody’s lifetime in the very near future,” said Faron Anslow, a climatologist for the Pacific Climate Impacts Consortium, a climate service center based at the University of Victoria in British Columbia.

The infamous heat dome was indeed rare, Anslow told growers in February at the “Feeling the Heat” webinar, hosted by the Okanagan Horticultural Advisor’s Group of British Columbia. The epicenter of the event was responsible for 595 heat-related deaths in British Colombia. By historical or even current standards, the scorching late-spring heat was a once-in-multiple-generations event, Anslow said.

But climate change will make it more likely in the future. If the global average temperature increases by 2 degrees Celsius over preindustrial times — and most climate scenarios predict that mark by mid-century — such heat waves will happen once every five to 10 years, he said.

“The statistics of today are becoming irrelevant very rapidly into the future,” he said.

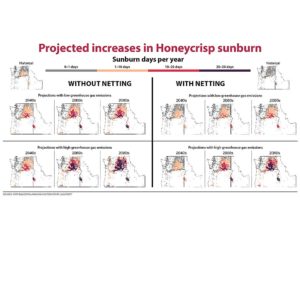

Washington State University climate models show temperatures in Northwest tree fruit production regions increasing over time, past the point where shade netting and other heat mitigation measures will be sufficient to protect fruit (see “Apples in extreme heat”).

That gives pause to growers who spoke during the webinar and afterward with Good Fruit Grower.

Gary Wade, a cherry grower in The Dalles, Oregon, who picked only about half of his crop in 2021, said warmer temperatures themselves are not the problem in his eyes. The increase in erratic, extreme weather that seems to come with climate change concerns him more. The November 2014 deep freeze killed a lot of trees. That also was a once-in-a-generation event, he said, one that he’d hate to see become more common.

The heat wave of 2021 has him considering his variety and rootstock portfolio.

The Columbia Gorge growing area has been veering away from vigorous rootstocks, such as Mazzard, in favor of dwarfing options like Gisela and Krymsk. Those smaller roots did not perform as well though, he said.

“That might be the one thing that, first of all, we reconsider,” he said.

All varieties struggled, but Skeenas seemed to have it worse, Wade said.

Netting is not an option for his steep slopes, he said, but even fruit shaded by his KGB tree canopies was cooked.

“We had 118 degrees here … I don’t believe there was anything we could have done that would have actually salvaged our crop,” he said.

Matt Miles of Allan Bros. said netting didn’t help his company’s cherries in places, either. Allan Bros. has an entirely enclosed Rainier cherry block in the Yakima Valley under white shade netting.

“Lost the whole thing,” he said.

Molly Thurston of BC Tree Fruits of Kelowna, British Columbia, also said the heat wave gave her a lot to consider in her planting decisions this year.

Seradaye Lean, a field service representative for Consolidated Fruit Packers, said most cherry blocks in British Columbia are on traditional, free-standing trees, though growers are curious about high-density plantings such as UFO systems on dwarfing roots. Nobody is abandoning their interest, but last year’s heat wave throws one more question mark into the debate.

“It’s definitely a concern,” she said.

Lean also said the heat wave reiterated the importance of soil health. Trees in healthy soil survived. “There was still damage, but they didn’t collapse,” she said. A few cherry trees completely died from the heat.

For the good news, Matt Whiting, a WSU tree fruit physiologist with a specialty in cherries, does not expect much doubling due to the 2021 heat.

Heat one year can spell polycarpy — or fruit doubling — the following season. However, the heat wave hit before most cherry buds went through differentiation, Whiting said, the point when fruit and stem buds develop. That usually happens after harvest. In fact, early season heat may help a tree build up resistance for later.

“I don’t think we’re going to have a lot of doubling,” he said.

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment