Only baby cherry trees grow under the trellis poles and wires that once supported grape vines on Brad Klingele’s Yakima Valley vineyard.

Adjusting to an oversupply of wine grapes, Klingele planted Black Pearl cherries this year to partially replace 13 acres of Chardonnay wine grapes for which a winery did not renew his contract in 2017. He’s going to do the same thing in January next year with a nearby 11-acre Riesling block, pulling out the vines and replacing them with something other than grapes. He didn’t think he could find another buyer for them.

“It just didn’t seem like to me it was going to have the demand,” said Klingele, a third-generation tree fruit and grape grower for CJ Orchards in Prosser, Washington.

Growers are making similar decisions up and down the West Coast, home to over 90 percent of the nation’s wine industry. For the past few years, demand for grapes has been flat and wineries have become more selective about which contracts they renew, as consumer preferences changed more quickly than producers could pivot.

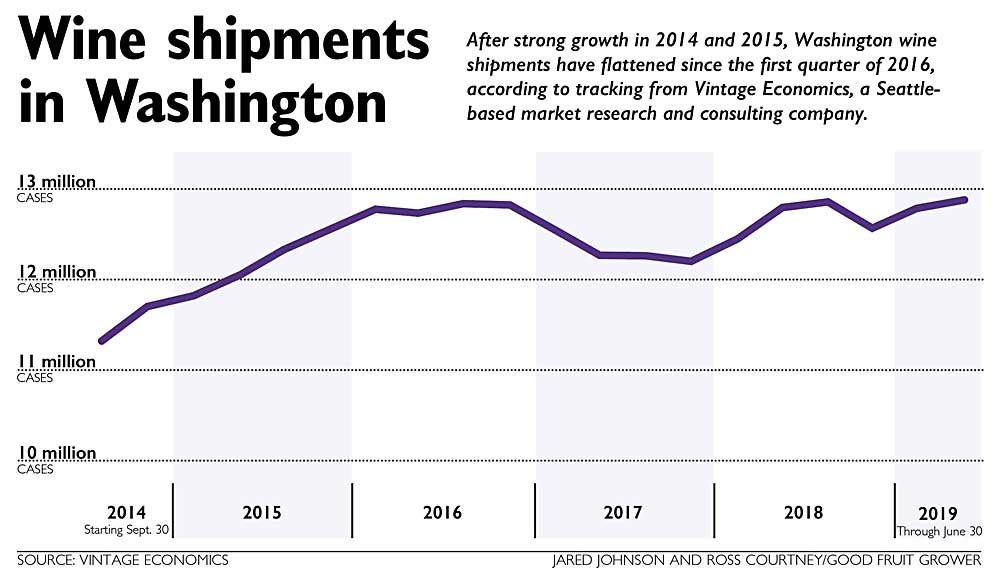

In Washington, packaged wine shipments have slowed since 2016 and have shown virtually zero growth in the past 12 months, said Chris Bitter of Vintage Economics, a Seattle-based wine market research firm. The problem is more pronounced with wines in the $11 per bottle and under price range, Bitter said. Demand for those is outright declining. In fact, the cheaper the bottle, the worse the performance.

Premium wine, on the other hand, is still going up, albeit more slowly.

Broadly, demand is sluggish around the globe. Wine now competes with spirits, craft beer, cider, hard seltzer and other drinks that weren’t even in the alcoholic beverage category a few years ago, Bitter said. Meanwhile, demographics have changed. Baby boomers are drinking less wine as they age, while younger generations simply have fewer people and more drink options, not to mention cannabis. Also, more consumers seem to be worried about the health impacts of alcohol.

Supply and demand

Ste. Michelle Wine Estates, which crushes about 60 percent of Washington’s wine grapes, hit a turning point after the large 2016 crop. The industry is still adjusting as more grape vines reach fruitfulness.

“You always tend to overshoot if you’re planting to meet increasing demand,” said Kevin Corliss, vice president of vineyards.

Since then, Corliss and Ste. Michelle have been “culling the herd” by not renewing contracts as they expire, gradually cutting down on the grapes they crush and the growers they crush for. Some are one-year contracts, some have been in place for over a decade.

“As contracts come up, we’re taking the opportunity to get out of them,” Corliss said.

The company still makes very few spot purchases for unusual varieties but is not contracting any new acreage, he said.

Each year, growers sometimes ask to be released from their contracts; that is, keep some of their own fruit to sell or make their own wine. The frequency of those releases has not changed, he said.

Generally speaking, the company favors growers’ new blocks over older ones. Old blocks can still produce quality grapes, Corliss said, but odds are higher they will struggle more with viruses and low production.

The well-known varieties — Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Syrah, Chardonnay, Riesling, Sauvignon Blanc — are struggling the most, Corliss said. In contrast, some of the niche varieties, such as the Rhone variety Grenache, still have high demand, though their acreages are small. Syrah might also weather the storm relatively well because it blends well with several other varieties, though he doesn’t recommend growers rush out and plant it.

Corliss blames the problems on a cycle of supply and demand. As recently as 2014, the industry was chanting “Cab is king.” So, growers planted, but demand flattened while production levels increased as blocks came online. The problem reached its peak after the larger-than-expected 2016 harvest, he said.

The industry will emerge into another round of high demand for grapes, Corliss said. “It’s part of a cycle and we’re going to have a reset period.”

Vicky Scharlau, executive director of Washington Winegrowers, agreed, calling down periods inevitable.

“Did we know it was coming?” she said. “It’s always coming.”

Her organization doesn’t track contracts, but she has heard anecdotally that wineries are renewing them at a slower pace and reducing the volume when they do renew. This year’s harvest, expected to be low due to cool weather, may ease some of the glut.

Corliss and Scharlau suggest that the industry consider using the sluggish period to renew, removing some of the older, less-productive blocks, especially those with viruses, such as leaf roll and red blotch, or grafting over with new varieties.

Also, look beyond the usual suspects when searching for new contracts, Scharlau said. Consider selling out of state or contacting a brokerage firm.

“Don’t look at your market opportunities with blinders on,” she said.

And don’t plant without a contract — something most industry groups preach over and over.

Washington growers are generally good about that, Scharlau said, due to the structure of the industry. She doesn’t know the share of contracted grapes but suspects it’s higher than California’s, mostly because Ste. Michelle buys contracts in advance at almost 100 percent of its grapes and makes up such a large share of the state’s industry.

Wheel of fortune

California, also in a state of overplanting, is roughly contracted at 85 percent, said Brian Clements, vice president and partner of Turrentine Brokerage of Novato, California. Prices for those not under contract fell quickly. What sales desks had projected as 6 percent growth has now become 2 percent growth, he said.

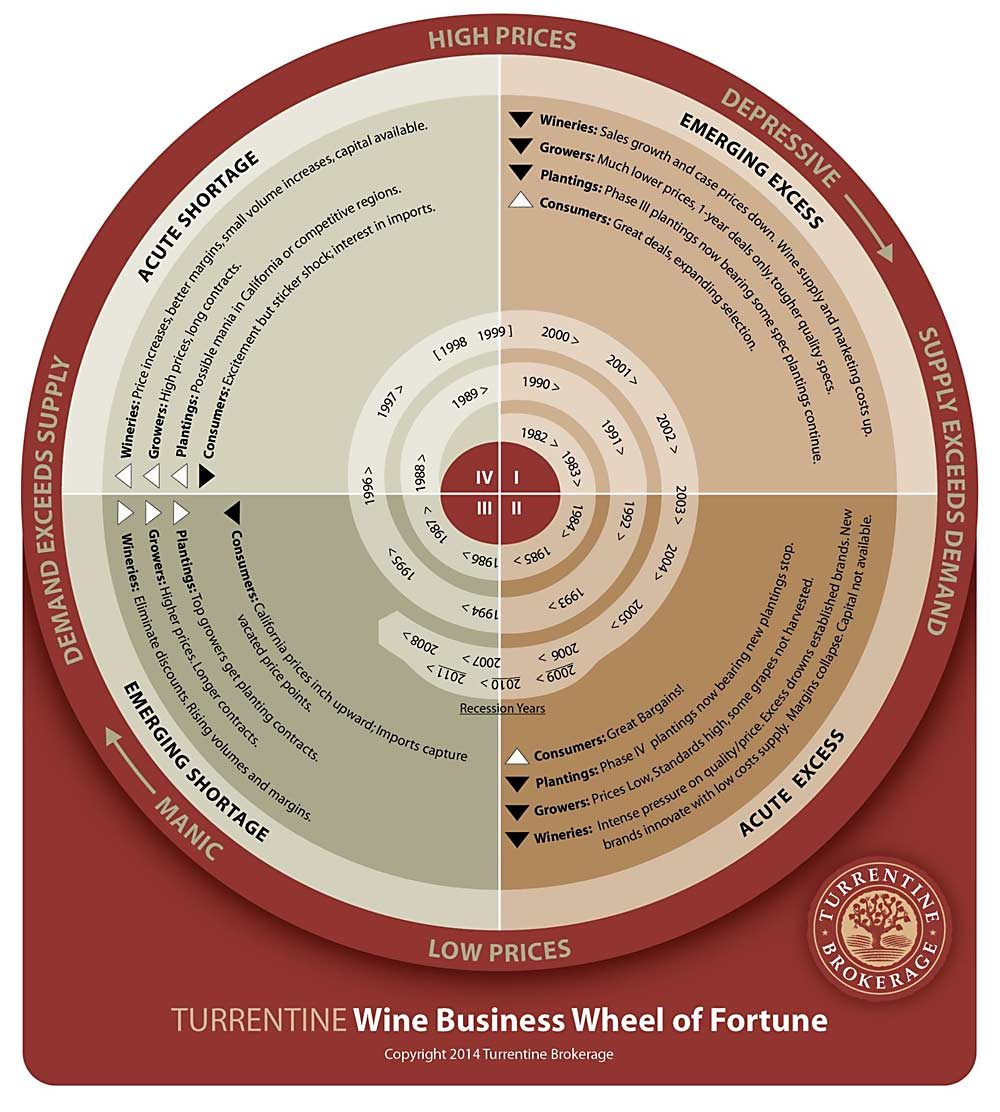

But the cycle metaphor applies in California, too, he said. In fact, his company even has a graphic for it — the Turrentine Wine Business Wheel of Fortune, which plots the years since 1982 on a four-quadrant cycle of fluctuating wine grape demand. Corliss at Ste. Michelle made references to the wheel, while University of California, Davis classes use it in their economic illustrations.

Right now, the industry up and down the West Coast squarely falls into Quadrant II, named Acute Excess, characterized by a halt in new plantings, low prices for grapes, high standards from wineries and some grapes simply not harvested.

Turrentine saw it coming when bulk wine prices started to decrease, Clements said. Bulk wine provides a pressure relief valve for wineries with too much wine in their tanks for their bottled brands. California has a bigger bulk wine market than Washington, he said.

If times seem dark for growers, Clements reminded them that wineries feel the pressure, too. During times of excess, they discount wines, earn smaller margins or even lose money and struggle to capitalize.

The good news: On the horizon is Quadrant III, Emerging Shortage, which should see those trends swing back to the positive side. No boom or bust is permanent in the wine business.

“It’s a tough time, but it’s going to get better,” he said.

Growers scramble and adjust

Colin Morrell, a grower and viticulture consultant from Benton City, Washington, and his vineyard manager have better contacts than most growers, but even they struggled recently to sell some of their Cabernet and Malbec. Some of those grapes were on a contract but the company asked him to try to sell elsewhere. He did, but it was hard.

“It used to be a lot easier to sell grapes, I can tell you that much,” Morrell said.

A bright spot in the wine industry is rosé, made from a wide variety of grapes, he said.

“I think the industry is going to be in good shape in the long run,” he said. “But I think people need to be careful just going out and planting without a plan and without a contract.”

Olsen Brothers Ranches does have a plan, one that does not involve blocks of Syrah and Cabernet Sauvignon that were planted in the 1990s and hampered by viruses. The wineries that once bought them did not renew contracts.

In September, as the Benton City company’s apple harvest proceeded at a breakneck pace all around them, those vines lay in giant heaps in vacant fields awaiting winter burning.

Olsen Brothers plans to plant more apples in one block, eventually, said Leif Olsen, one of his family company’s managing partners. The future is uncertain for the other.

Either way, he doesn’t expect the demand will return soon. “I think it’s going to take multiple years,” he said. •

—by Ross Courtney

[…] In an article written by Ross Courtney titled, ‘Growers switch gears after grape glut, Wine grape industry hits period of oversupply, lower prices.’, Brian Clements discussed the 2019 Grape Market and reviews the Turrentine Wheel. To read the article, Click Here. […]