Banchless, multileader trees open new windows for more efficient production, due to lower cost per unit of fruit, and/or higher prices that the orchardist receives per unit of fruit.

Orchardists and researchers well know trees (especially apples) that are closely planted and arranged so that they intercept the optimum sunlight, improve productivity, and keep costs in check.

Should canopies be vertical or angled? Both have merits. Orchardists usually decide according to locality, crop, experience, quality of labor available, advice from progressive orchardists and researchers, and whether the system can be mechanized.

There are many systems that orchardists can use successfully. However, there is room for improving the bottom line with a modified system. One way is to use the multileader trees advocated by orchardists and researchers in several countries.

Features of a branchless four-leader system are:

—The architecture of the tree is simple with only a primary structure of a short trunk with two or more leaders per tree that are dressed with short fruiting wood.

—Branches are neither created nor manipulated.

—The trees are closely planted and supported by a trellis to form canopies that are either vertical or angled.

—The branchless leaders are neither basitonic nor acrotonic, meaning that branching is neither predominantly toward the tip of the leader or the base.

—The thin, two-dimensional canopy is uniformly filled with leaders. There are no gaps in the upper part of the canopy.

—The system is easily mechanized.

—At first, the roots are not restricted and push the trees to fill their spaces on the trellis as quickly as possible, so they have a short vegetative phase. Later, when roots have filled their space and are then restricted, they help to control vigor of the leaders.

—Vigor is equally divided over four leaders, and more easily controlled than in trees with two leaders. The rootstock controls vigor less.

—The crop can be accurately targeted, monitored and managed, because all four leaders have the same number of fruit. During winter, bud counts help to determine the intensity of pruning needed to establish the crop load for the coming season.

—Unskilled labor can easily learn to prune the trees and to thin and harvest the fruit.

—Some leaders can be used as pollinizers; this improves the pollination strength, and individual pollinizer trees are not needed.

—The thin canopies improve air circulation, allow good spray coverage, reduce spray drift, and need less spray material per acre.

—Leaders can be renewed when they become less productive. One leader is removed at the time and is replaced by a new leader.

—Nursery trees do not need to be double-budded, which is a patented method and is costly.

—Training of multileader trees preferably starts in the nursery, when they are headed to force development of side shoots. After the trees have been planted in the orchard, suitable forks are selected and cut back. The trees then generate several shoots out of their heads. Four shoots are then gradually selected to make sure that the future leaders are uniform in size and thickness.

—After they are planted, nursery trees are headed, which helps prevent transplant shock.

—Infection by fire blight can be detected early, so that the trees will not be damaged much. When an infected leader is removed in spring or early summer, a new shoot soon replaces the infected leader.

—In research, multileader trees can simplify statistical designs of experiments, because individual leaders rather than whole trees, can be used for treatments.

—Many temperate, subtropical, tropical and ultratropical fruit crops adapt well to the branchless multileader system, making it one of the most versatile state-of-the-art production systems.

Manage from ground

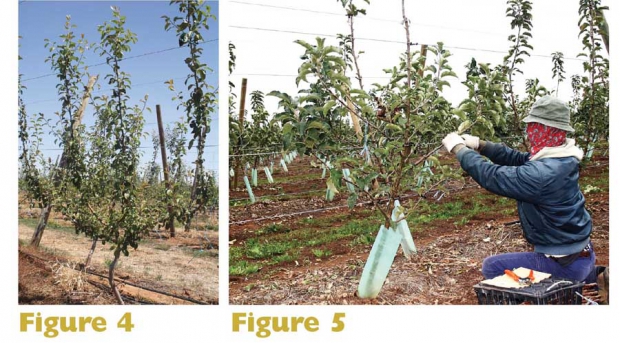

Open-V systems, such as the Open Tatura, incorporate all of the above features. As well, the canopy of the Open Tatura has a higher surface area that orchardists can manage from the ground, whereas (at the same spacing and density), the much taller vertical Fruiting Wall needs ladders or platforms.

When fruit trees are managed from the ground, it is easier for the orchardist, labor is more efficient, the labor force can be expanded to include male and female workers of different ages, and it is easier to manage unskilled labor.

The small trees have less internal shading than large trees do.

Regulations and penalties for occupational health and safety may eventually force orchardists to work from the ground. Platforms and other mechanical aids have less value in small orchards that risk being overcapitalized and in countries with plenty of cheap labor.

On the Open Tatura system, some stone fruit plantings trained with four leaders produce a crop in the second year, and most types of fruit trees reach their plateau yield within six years. Swiss researchers have recently shown that V-shaped canopies have higher yields and fruit of better quality than vertical canopies do. However, it is more expensive to establish an orchard with V-shaped trees than an orchard with vertically trained trees.

Open Tatura usually has rows that are 4.5 meters (15 feet) wide, giving more space for equipment and bins to pass between rows than there is in the popular vertical Fruiting Wall with only 3.5 meters (11.5 feet) between rows.

Fruit on the Open Tatura is generally little damaged by wind. In parts of New Zealand and the United States, angled canopies are preferred where strong winds are a problem. In 2012, an Open Tatura orchard in north Queensland, Australia, withstood cyclonic winds of 280 kilometers (175 miles) per hour, while freestanding trees and trees on T-trellis were ripped out of the ground. Angled canopies are successful, because the wind skims over the rough elements of the high-density trees.

For an Open Tatura with four-leader trees, a planting density of 2,222 trees per hectare (900 per acre) is affordable. With four leaders per tree and two leaders on each side of the trunk, there are 500 millimetres (20 inches) between leaders. On the other hand, the canopy develops more slowly with fewer trees per hectare and six leaders per tree, because it takes more time, care, and leader-bending than with four leaders.

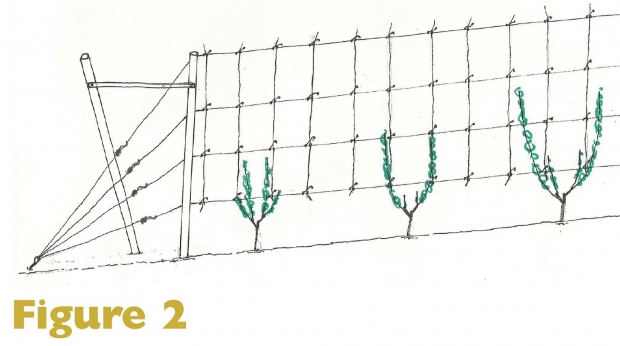

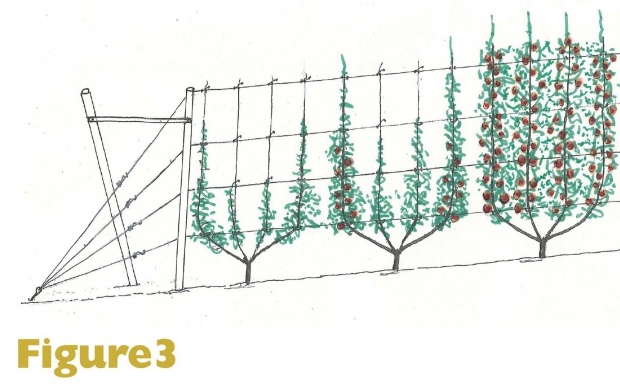

There is one pitfall in the early development of the four-leader system. The inner two shoots tend to be more vigorous than the outer two shoots (see Figure 1). The orchardist needs to subdue (cut back to a short stub) the two inner shoots to give the two outer shoots a good head start. At the end of the first growing season, the two inner shoots usually catch up with the growth of the two outer shoots (see Figures 2 and 3).

of the two inner shoots has created four uniform leaders. (Courtesy Bas Van den Ende)

Some countries and regions specialize in apples because different types of spindle trees on low-vigor rootstocks appear to produce profitable apples. However, in countries like Australia, many orchardists grow different cultivars of both stone and pome fruit, and use various systems for training trees.

Some systems continue to evolve to suit different fruit species and conditions. The branchless multileader tree, for example, can be used for both angled and vertical trees and can maintain optimum and affordable tree density. Trees are managed simply and vigor controlled without size-controlling rootstocks, yet yield and packouts of fruit of high quality are increased. •

—by Bas van den Ende

Correction: The captions for figure illustrations included in this story were incorrectly labeled when published. The captions have been corrected as of February 25, 2015.

Leave A Comment