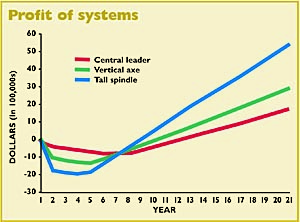

The Michigan study compared three systems—from left, central leader, vertical axe, and tall spindle.

It costs a lot of money to put in a new apple orchard in Michigan, and it takes 9 to 12 years to recover all the expenses incurred up until then. High density systems cost more to establish but are, in the long run, more profitable. After the first year, you’ll have sunk $15,000 into building an acre of trees in a tall spindle orchard. But, after 20 years, you can expect to have accumulated $50,000 per acre in profit from it, more than twice the profit lower density systems will generate.

Those are some bottom-line conclusions in the new Apple Costs of Production study recently completed in Michigan by Phil Schwallier and Amy Irish-Brown, two Michigan State University Extension horticulturists serving west central Michigan growers, including those on Fruit Ridge north of Grand Rapids.

The study uses 2008 information and updates a study done ten years earlier. There are 20 sheets of data describing the systems, the assumptions made, the costs incurred, the prices paid, the hours involved, the expected price of fresh apples, the expense and income stream, year by year, all in great detail.

It was completed with support from the Michigan Apple Committee and MACMA, Michigan’s processing apple marketing group.

The study compares three systems and three tree densities—central leader, vertical axe, and tall spindle.

This project started with a survey of a study group of west Michigan growers at a review meeting. Practices and material costs were gathered and reviewed with the growers, and an average of these practices and materials were placed in the costs study, the authors said. Yield figures were also gathered from growers in the survey.

The Michigan study affirms what studies in New York and other areas have shown: The tall spindle system, with its well-feathered, costlier trees, high planting densities, irrigation, and expensive trellis training system, gets up and running faster, and yields top out earlier and higher. In this study, tall spindle orchards reached their top yield of 1,000 bushels per acre by year five. Vertical axe orchards reach their top yield of 750 bushels per acre in year seven. Central leader orchards reach their top yield of 650 bushels per acre in year nine. (In the grower survey, however, some thought 650 was too low and that 700 bushels was a better number for the central leader system, Schwallier said.)

The Michigan study affirms what studies in New York and other areas have shown: The tall spindle system, with its well-feathered, costlier trees, high planting densities, irrigation, and expensive trellis training system, gets up and running faster, and yields top out earlier and higher. In this study, tall spindle orchards reached their top yield of 1,000 bushels per acre by year five. Vertical axe orchards reach their top yield of 750 bushels per acre in year seven. Central leader orchards reach their top yield of 650 bushels per acre in year nine. (In the grower survey, however, some thought 650 was too low and that 700 bushels was a better number for the central leader system, Schwallier said.)

It only takes 202 trees per acre to plant a central leader orchard on a 12- by 18-foot spacing. The vertical axe system requires 519 trees on a 6- by 14-foot spacing. The tall spindle system uses 908 or 1,200 trees per acre on spacings of 4 x 12 or 3 x 11. The cost of well-feathered trees was plugged in at $7.50 each and used in all systems.

All three systems incurred a cost of just under $800 to prepare the site for planting. In the planting year, however, the central leader orchard incurred a cost of $2,265 with $1,500 going for trees. The vertical axe system cost $8,430 in the planting year—$4,670 for trees, $1,200 for drip irrigation, and $1,660 for trellis. The tall spindle system cost $15,070 in the planting year—$9,075 for trees, $1,300 for irrigation, and $2,500 for trellis.

Land cost was not included in the cost estimates.

Drip irrigation was another cost that varied by orchard system. Central leader orchards in mid-Michigan do not need irrigation, but both new vertical axe and tall spindle orchards are being irrigated now, at a cost of more than $1,100 per acre.

Trellis systems are also not needed in central leader orchards. The trellises in vertical axe orchards, consisting of posts and three wires, cost $1,300 per acre, and for the tall spindle orchards, supported on five wires and with more rows of trees per acre, the cost was just under $2,500 per acre.

But the profit potential of the various systems is quite different. In the central leader system, growers never get into the really deep hole; costs top out in year 11, when accumulated profit is a negative $7,996 and then annual income starts to surpass annual costs. By year 17, the total debt is wiped out and profit, after annual expenses, rises to $1,997 per year. After 20 years, the orchard has generated $17,277 per acre in profit.

The curve is different for vertical axe orchards. By year nine, growers are in the hole by $13,154. The next year, annual profit turns positive (surpassing annual costs), and the grower accumulates profits at a rate of $2,678 a year. After 20 years, this orchard has generated $28,596 per acre in profit for the owner.

The tall spindle system is more extreme at both ends. The grower has accumulated a large debt of $19,530 per acre by year three, but the orchard’s income begins to surpass annual costs already in year four and by year five is generating its maximum sustained annual profit of $4,514 per acre. By year nine, the debt is wiped out. After 20 years, the orchard has generated a profit of $53,829 per acre.

The chart “Profit of systems” shows the profit curves for the three systems.

Interestingly, the new study shows much different results than the study done ten years earlier. In that study, returns after 20 years were nearly the same in each of three systems compared. The central leader system accumulated the highest profit, $12,750, followed by $12,589 in the slender spindle system, and $11,271 in vertical axe.

In the old study, the tall spindle was not represented; the slender spindle system was in use at the time. Trees in the slender spindle system are shorter—8 feet compared to 12—and are supported by individual tree posts without wire trellising. Irrigation was not included in the picture either.

The yield advantage of one system over another was less. In the central leader system of 1998, maximum yields of 800 bushels per acre were reached in year eight. In the 2008 study, the assumed maximum yield was lower—650 bushels per acre, reached in year nine.

In the vertical axe system of 1998, maximum yields of 825 bushels per acre were reached in year six. Those numbers are changed in the 2008 study, where maximum yields of 750 bushels per acre were reached in year seven.

The big change comes in what tall spindle can do compared to slender spindle. Tall spindle’s mature yield capacity was rated at 1,000 bushels per acre in the 2008 study. Top yields for slender spindle were pegged at 850 bushels per acre.

The new study is in Excel format and can be downloaded from the Web site www.apples.msu.edu.

Tkanks for providing such a grea /excellant /valuable information espacially for orchdists

Do you have a direct link 2008 study?