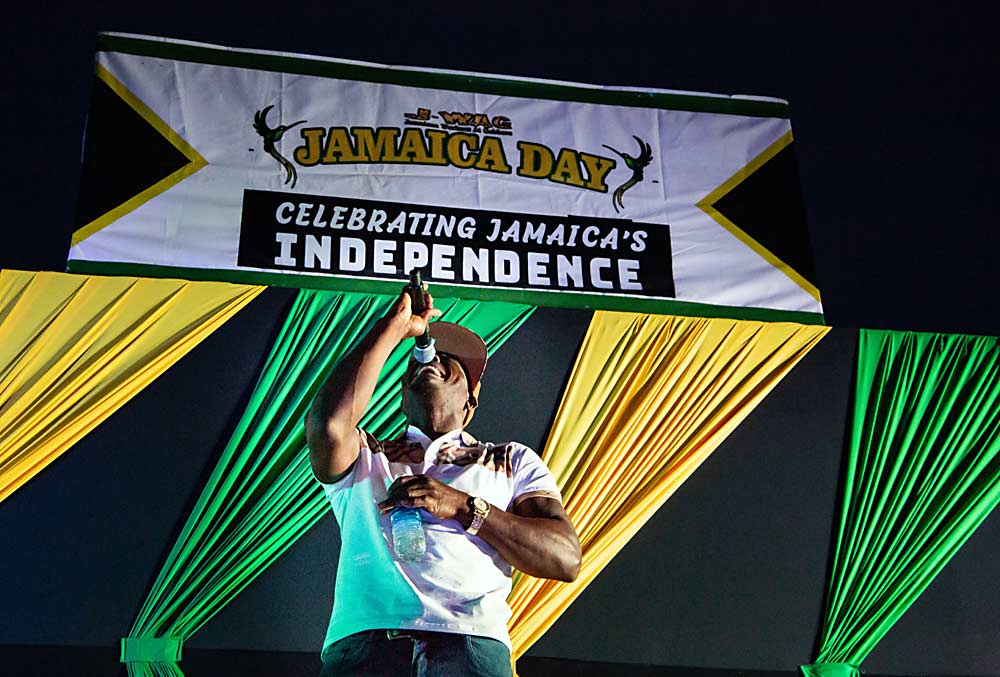

On a flatbed truck stage, under Jamaican flags and a smoky North Central Washington sky, Oniel Johnson belted out “One Day at a Time.”

Johnson, who has spent 18 seasons as an H-2A worker, was one of a handful of open-mic singers contributing to Jamaica Day, an annual celebration held by the workers of Gebbers Farms in Brewster, Washington. The event is an opportunity to honor their home country and express gratitude for the chance to improve the lives of their families back home by working half the year in American orchards.

Johnson does not wonder what life would be like without it.

“You cannot know what would have happened,” said the father of three. “Because I’m in it, I have to give thanks.”

Every year, the workers, community residents and a few Gebbers family members gather downtown for a night of art, jerk meat cooked over open fires and a bouncy amalgamation of gospel songs, reggae and pop dance tracks. The festival anchors a yearlong charity drive for Jamaican causes, usually agricultural scholarships. In 2022, it raised about $4,000 (U.S. dollars).

“It’s important because we have so many people in Jamaica who are less fortunate than the workers we have here,” said Sheldon Brown, a liaison officer for the Jamaican Embassy in Washington, D.C., who stays in Brewster during the crop year. “The opportunity is huge for them. For the few of them who get that opportunity, it’s good to give back.”

The event pays homage to Aug. 6, 1962, the date on which the young nation gained full independence from the United Kingdom. The Brewster workers celebrate when the cycles of tree fruit allow, usually sometime in August, during a lull between cherry and apple harvests.

On the farm

Jamaicans have been helping on farms in Eastern U.S. states since 1943 through a guest worker program similar to the Bracero Program, which allowed workers from Mexico to fill in on farms for U.S. servicemen and servicewomen fighting in World War II. Over the years, those evolved into the H-2A programs.

Today, most H-2A farmworkers in the United States come from Mexico: 276,000 of the 298,000 total in 2022, according to U.S. State Department statistics. Jamaica is a distant second at 4,800. Guatemala sends the third most, at just under 3,000.

In Jamaica, the Ministry of Labour and Social Security screens potential employees for the opportunities in America. Not all nations do that, said Ryan Ogburn, director of visa services for wafla, the leading H-2A processor in Washington and Oregon.

At Gebbers Farms, one of the largest agricultural employers in the state, Jamaicans helped renew the company’s trust in the H-2A program.

Gebbers had tried hiring H-2A labor from Mexico in the early 1980s but struggled to make the bureaucratic program work for the company. Decades later, company president Cass Gebbers visited a New York orchardist and, by happenstance, struck up a chat with an H-2A foreman from Jamaica who was overseeing a crew.

After a few references from other growers, Gebbers Farms tried hiring their own crew from Jamaica in 2010.

Happy with the results, they expanded their H-2A recruitment to Mexico. This year, Gebbers contracted 364 H-2A employees from Jamaica — 300 men, 64 women. By comparison, Gebbers has roughly 3,000 Mexican workers on H-2A visas.

Gebbers, his brother Mac, other family members and non-Jamaican employees often attend the annual festival. The company has matched some of their donations over the years.

“It’s a wonderful way to support a wonderful group,” Cass Gebbers said.

The Jamaican workers first held the festival in 2012, to mark their country’s 50th anniversary of independence, in the farm’s labor camp away from town. After a hiatus for the pandemic, they moved it in 2022 to an empty lot in downtown Brewster, next to a market that offers money wiring services.

Life in Jamaica

The Caribbean island nation is more rural than the beach-photo-covered tourist brochures would have you believe. Many of the Gebbers workers own their own small, subsistence farms.

Maureen Grove is one of them.

The single mother of three has worked for Gebbers since 2017. She uses her Gebbers wages to save, send her three children to school — one of them to chef’s training — and invest in her farm that breeds pigs and produces cabbages, carrots and tomatoes. Her sister and brother-in-law, as well as neighbors, help manage the place in her absence, supervising her employees.

On a good year, after expenses, she can still save about $5,000 (U.S. dollars).

“I miss my kids, but it’s a chance to get a better life for them,” she said.

She grew up the oldest of seven siblings in a one-room house, poor with no father and a strained relationship with her mother. She often slept at neighbors’ homes, or in parks, and ran away at a young age.

Of the Gebbers work, she said, “It’s the best thing that ever happened to me.”

Johnson does not consider his family poor by Jamaican standards. However, work in his country is inconsistent. When home, he finds spotty work in electrical installation, construction and running his small rice farm. The steady flow of U.S. farm work each year has helped him to send his three children to high school, which is not free in Jamaica, and one to college.

Someday, he would like to earn enough to just work on his own ranch in Jamaica, raising cattle and pigs.

“Each year, we come with a goal,” he said.

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment