Though technically retired, John Kuntz still spent the 2019 fruit season getting up at 4:30 each morning to tend to what’s left of the orchard he sold last year. Either he was hanging nets over his few cherry trees, thinning his apples or fixing water lines amid the holes and stumps of removed trees on his hillside apple orchard overlooking Central Washington’s picturesque Lake Chelan.

Kuntz, a third-generation grower, and his wife, Sherry, still have their pretty view and a few hobby trees, but they are one of many small-acreage apple growers in the United States who have sold their farms, making way for the insatiable march of consolidation. Orchards are few and large, and the trend is toward fewer and larger.

“It’s happening to everybody,” said Kuntz, 71.

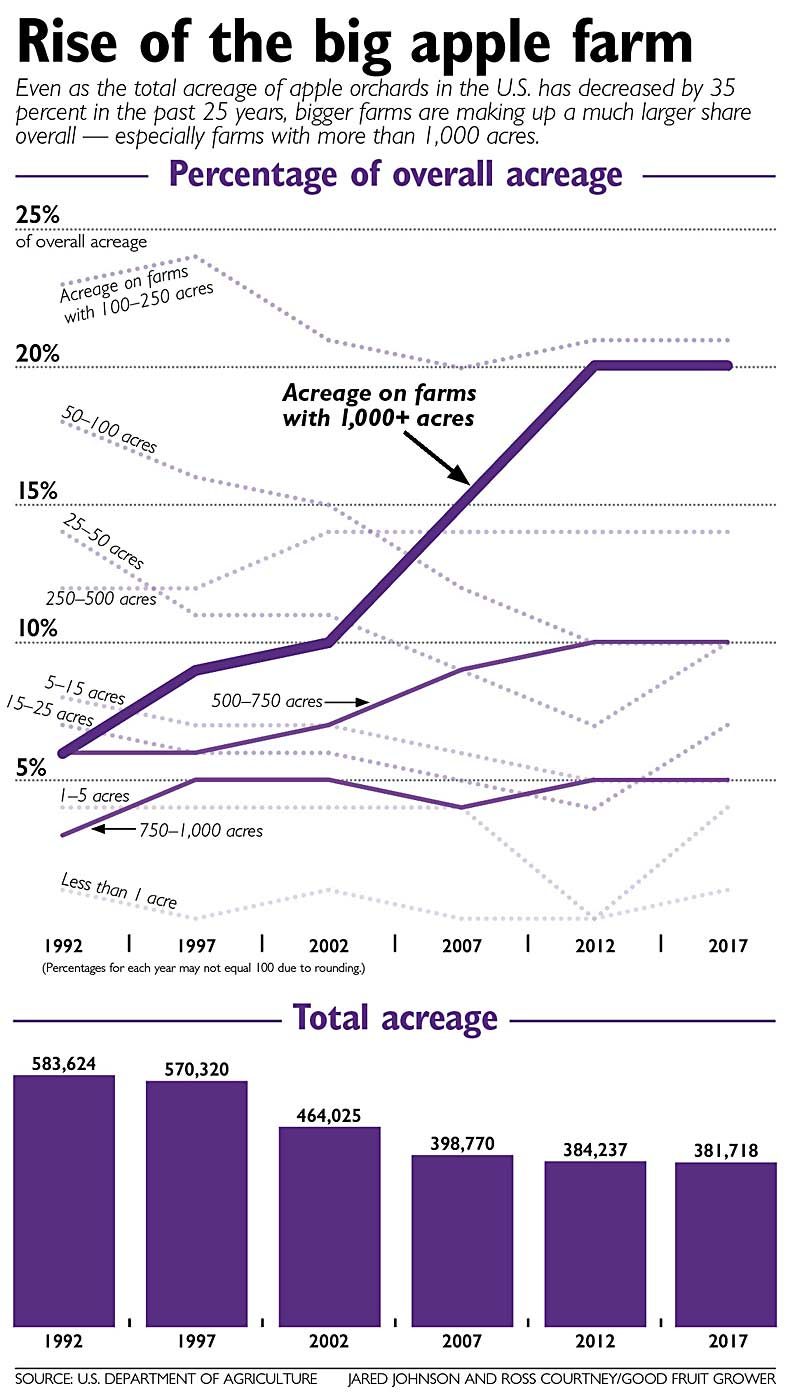

Indeed. None of this is surprising, but the latest ag census by the U.S. Department of Agriculture reveals stark new figures for a trend that dates back decades. In 2017, 35 percent of the apple acreage in the United States was on farms of 500 acres or more. In 1992, those farms represented only 15 percent.

The numbers deserve some caveats. The census counts growers with a fraction of an acre — hobbyists with just a few trees in their yard — as farms, skewing the acreage weight. Meanwhile, farming families face myriad decisions; trying to compete with larger farms is just one of them. But the curve has been moving for the past 25 years, indicating many growers are leaving the business because they have to, not because they want to.

“People don’t necessarily exit a business because they don’t like it, they exit the business because they can’t make a profit from it,” said Jon DeVaney, president of the Washington State Tree Fruit Association.

Causes

The association, which lobbies on behalf of the fruit industry, finds the numbers frustrating because new regulations seem to disproportionately affect small growers, even though lawmakers typically express fondness for small farms. For example, when payroll rules become more complex, growers with human resources departments can more easily comply. New food safety requirements are expensive, so larger farms can better afford to implement them.

“You can’t say you like one thing, but hurt that thing with policies,” DeVaney said.

Simple economics also drive much of the consolidation, said Karina Gallardo, a Washington State University agricultural economist who writes a production cost and enterprise budget study about the fruit industry every four or five years.

Her latest version is scheduled for release this fall, so she declined to discuss hard figures. But she said she has noticed a spike in the costs of production this go-round. Land prices, trellis systems, equipment, labor and all the other factors sometimes called “inputs” are rising quickly, more quickly than noted in her previous report in 2014.

“That investment is becoming difficult for smaller growers,” she said.

Take netting for example, she said. Sunburn netting once was an experimental idea, but it’s becoming the norm now as climate changes and research show the advantages for sunburn-sensitive varieties such as Honeycrisp.

Labor prices also have spiked. As domestic workers become harder to find, more growers are using the H-2A program, which typically adds about 25 percent to labor costs, she said. Growers who use H-2A workers must pay the federally mandated Adverse Effect Wage Rate, or AEWR, for contracted and local workers. In 2016, the AEWR was $12.62 per hour. This year, it’s $15.03. That’s a 20-percent jump in three years. Growers who don’t use H-2A have to keep pace with their pay rates to compete for workers, as well.

Big stores and small towns

Desmond O’Rourke, a global tree fruit market analyst from Pullman, Washington, said consolidation among retailers is part of the explanation. Bigger grocery chains typically purchase from a few large suppliers that deliver apples 12 months a year. That prompts packing firms to partner under unified sales firms. In the 1980s, Washington had about 100 sales desks; today, about 10.

Those big stores, such as Costco Wholesale Corp. and Walmart Inc., demand a lot from their suppliers, often holding their own audits for food safety, worker treatment and environmental concerns. Then, the global industry’s shift to proprietary varieties leaves small growers out. Companies that own rights usually want to deal with larger, more capitalized farms that can efficiently produce the required volumes to meet commercialization goals.

O’Rourke recalls packing sheds up and down the Columbia and Okanogan rivers through North Central Washington. “Virtually all of those are gone and so is the employment in the community,” he said.

The effects go beyond just the farm, O’Rourke said. Consolidation drains rural economies of jobs, influence and a sense of community.

The next step

Each family’s decision is personal amid all these forces.

John and Sherry Kuntz have two sons who have jobs off the farm and weren’t that involved in the business anyway. John had worked construction full time for most of his career, helping his brother, Norm, and his mother, Lenore, tend to the family orchard on the weekends.

His grandparents planted their first orchard around 1900 in the Wenatchee, Washington, area. His family moved to Chelan in the 1960s and cleared the sagebrush to start the Triple K Ranch. At its peak in the late 1980s, it covered about 75 acres, packing most of his fruit at some of the Chelan-area cooperatives that themselves have shifted and morphed through consolidations over the years.

Last year, for his final crop, Kuntz received $5 per box in returns for his Galas, but he traces the downfall way back to the 1989 Alar scare. The industry overall recovered, but his family struggled to afford planting new varieties, upgrading systems and otherwise keeping pace with the modern demands of horticulture.

So, last year he sold the property to two of his nephews who have plans for vacation rentals or wine grapes, or a combination thereof. He is helping them uproot trees, move a drain field and otherwise prepare the ground for its next life. He kept one or two trees of each variety, just to share fruit with his friends and family members.

“It’s been in the family for over 100 years, so yeah, yeah I miss it,” he said. •

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment