(Courtesy Bas van den Ende)

Virtually everything that you do in the orchard affects the quality of fruit, so you must always keep size, maturity, and taste in mind. Large fruit brings more money than small fruit does. Not all of that is profit, because it costs more to produce large fruit.

The market demands that you consistently grow large peaches and nectarines of high quality. There is no money in growing small fruit.

To produce the sizes of peaches and nectarines that the market wants, you must know exactly what you are doing when you prune your trees in winter, and three or four months later when you thin the fruit. To prune your trees correctly, you must first know how many fruit of marketable size your trees can and should produce.

The whole process starts with the number of laterals that the trees have grown. Laterals that are about 300 millimeters long and have triple buds (two fruit buds with a leaf bud in between) are the foundation of your next crop. Since peach and nectarine trees only bear fruit on maiden (new) laterals, you actually have to manage two crops in the one year: the fruit that grows in the coming season and the laterals for the crop in the season thereafter. Large peaches and nectarines grow only on laterals of good quality. Watershoots, spent laterals, and short, thin laterals do not produce large fruit and contribute to shading. The flowers and fruit that these shoots and laterals produce rob the tree in spring of valuable reserves of nutrients and carbohydrates. Get rid of these watershoots and inferior laterals.

Prune your reference trees

Plan your pruning before your pruners start on the trees. Prune ten reference trees yourself. Mark them clearly with paint, so that you can refer back to them any time of the year and also show them to your pruners and thinners.

When you prune ten trees yourself, you will see how well or how badly good laterals are distributed throughout the trees. The upper part of the tree usually has the most and best laterals. The lower part of the tree, which can be excessively shaded, often struggles to generate good productive laterals. The shade that the tree casts upon itself limits the production of fruit more than anything else does. Peach and nectarine trees have canopies with dense foliage. It is common to see yellow leaves in midsummer and dead laterals in winter. The condition of the laterals in winter shows you how well you have managed sunlight in the previous summer. Summer pruning can alleviate internal shading to a large extent.

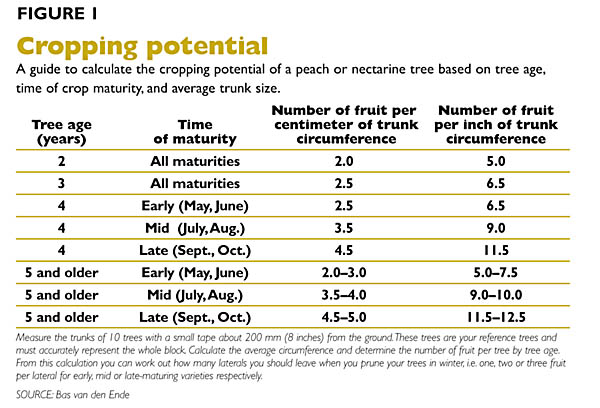

Having pruned your reference trees, you can now determine the cropping potential from the average number of laterals per tree. Peach and nectarine trees almost always set more fruit than is desired. You need to decide how many fruit you are going to leave per lateral after thinning. This should usually be between one and three fruit per lateral. Leave one fruit per lateral for young trees and early maturing varieties; two fruit per lateral for midseason varieties; and three fruit per lateral for late-maturing varieties. Multiply the number of laterals by the number of fruit per lateral to get the number of fruit per tree.

If you are not sure what the cropping potential of your young trees is, you can work this out from the average size of the trunks, as shown in Figure 1. When you have determined how many pieces of fruit should be left on each tree after thinning, you can work back to how many laterals you should leave on each tree in winter. This is called target pruning.

Calculating weight

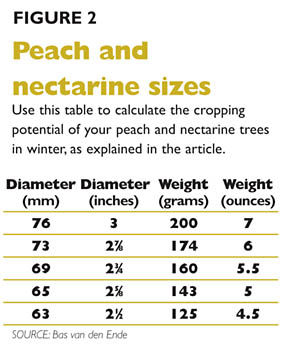

Use Figure 2 to calculate the weight of fruit per tree, per hectare/acre, or per block. The table shows you the average diameter and weight of peaches and nectarines of the two most profitable sizes. Multiply the weight by the number of fruit to calculate cropping potential

Use Figure 2 to calculate the weight of fruit per tree, per hectare/acre, or per block. The table shows you the average diameter and weight of peaches and nectarines of the two most profitable sizes. Multiply the weight by the number of fruit to calculate cropping potential

The following example shows how to calculate the cropping potential of your peach and nectarine trees in winter:

A planting of six-year-old white-fleshed peaches maturing in midseason has 1,200 trees per hectare and an average of 85 laterals per tree. Experience tells you that two fruit per lateral gives you premium size. This translates into 170 fruit per tree (85 x 2). The planting has the potential to produce 204,000 peaches per hectare (170 x 1,200). If the average weight of the fruit is 200 grams, the cropping potential is 34 kilograms per tree (200 x 170) or 40,800 kilograms (40.8 tons) per hectare (34 x 1,200).

In U.S. measurements, let’s assume the planting has 450 trees per acre with an average of 85 laterals per tree and two fruit per lateral. The one-acre planting has the potential to produce 76,500 peaches

(170 x 450). If the average weight of the fruit is 7 ounces (3-inch diameter), the cropping potential is 1,190 ounces (170 x 7 ounces), or 74.375 pounds per tree, which translates to 33,468.75 pounds per acre, or 16.7 tons per acre.

If you manage your trees and your labor well, and if you have Mother Nature on your side, you stand to pack 90 to 95 percent of the crop.

Maintain profitability

The best way to ensure that you consistently produce large peaches and nectarines of high quality is to train and prune your trees well, thin the fruit correctly at “tip-change” when the stone starts to harden, let the leaves and fruit see the sun, irrigate and fertilize well, and harvest the fruit at the correct maturity.

Growing of fruit is being buffeted by the winds of change, and like trees in an orchard, orchardists have to bend to survive. The driving force in profitability is high packouts of large fruit. In this day and age, an orchardist who focuses on yield per hectare at the expense of fruit size and quality is seriously mistaken.

As you sharpen your shears this winter in readiness to prune your peach and nectarine trees, realize that pruning is the most important horticultural practice (excluding irrigation) that an orchardist controls.

Bas Van den Ende is a tree fruit consultant in Australia’s Goulburn Valley.

Leave A Comment