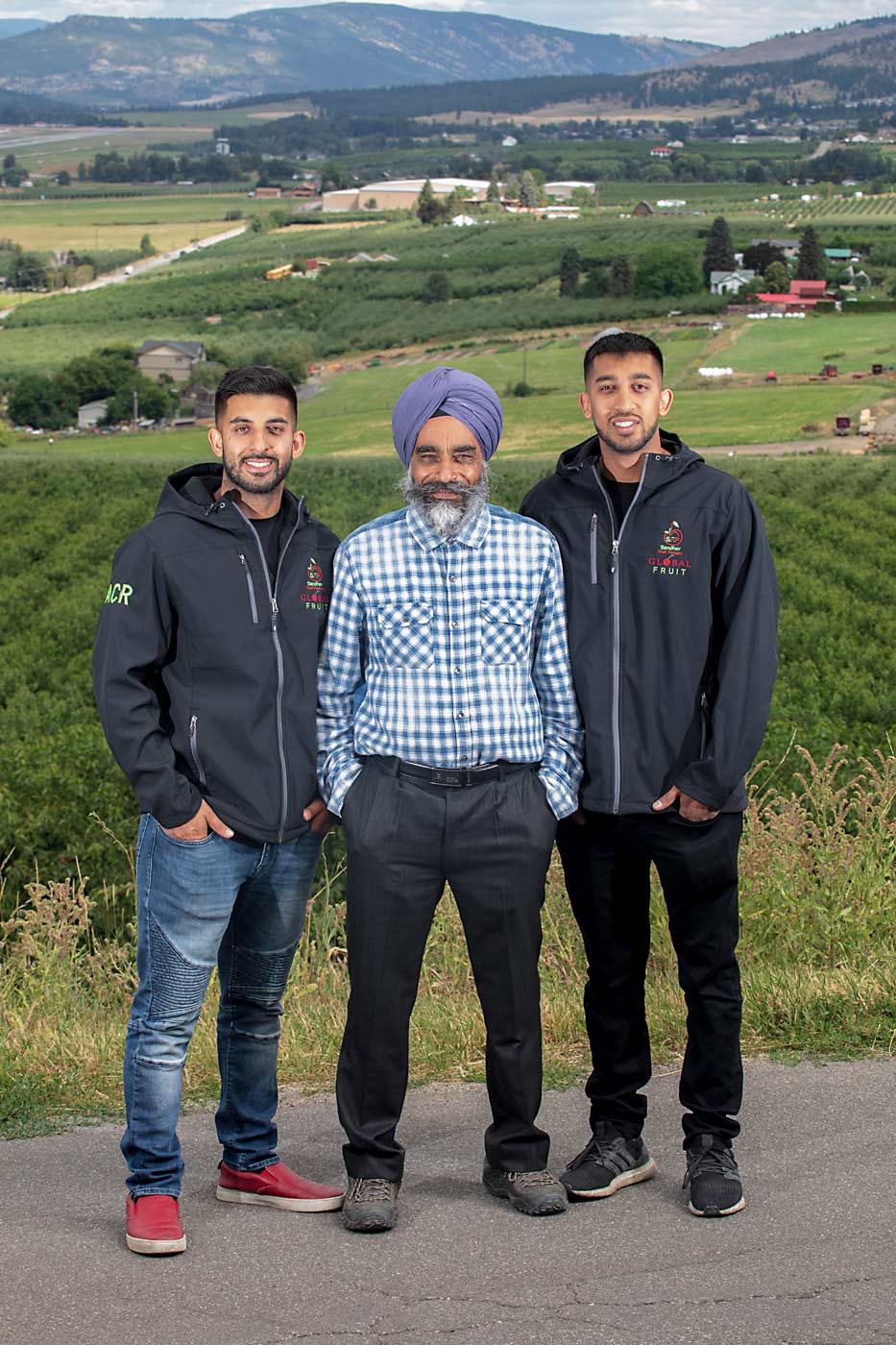

With a blue turban and a gray beard, the soft-spoken Bill Sandher stands over the maze of gleaming stainless steel at his upgraded cherry packing facility in Kelowna, British Columbia.

The Unitec equipment, as well as two new European orchard platforms, are among the latest incremental advancements in the tree fruit career Sandher has forged with hard work and an appreciation for land and legacy since moving from India as a teenager in 1982.

Such traits in families like his, those that trace their heritage to the state of Punjab, are helping to propel the tree fruit industry in British Columbia, where limited acreage, high land prices and a lack of new varieties have stagnated growth.

“The Indian community is really hardworking and are willing to take a risk,” Sandher said.

Driven by economic depression in India, Punjabis first migrated to British Columbia shortly after the turn of the 20th century. Most were men attracted to ample jobs in the lumber industry and agriculture.

In 1910, Canada established immigration laws that stratified those from different parts of the world. For example, immigrants from northern European countries were required to have at least $25 on them when they arrived; Asian immigrants $200. By midcentury, laws began to relax, allowing immigrants to sponsor family members, vote and buy land.

Land ownership became important to Punjabi immigrants, allowing them to meld their work and private lives around their traditions and families, according to the 1982 thesis “Accommodation and Cultural Persistence: The Case of the Sikhs and Portuguese in the Okanagan Valley of British Columbia,” by Annamma Joy, a University of British Columbia researcher.

Sikh is the primary religion practiced by Punjabi people. In the 2011 census, the most recent, 4.7 percent of British Columbia households surveyed called themselves Sikh.

That land importance continues today, Joy said. Many families are now led by their second and third generations in British Columbia. Some have left agriculture and many own wineries, but several stalwarts are expanding their fruit production businesses.

“Their families still own land, and hence they are quite wealthy,” Joy said in an email. “This is the classic immigrant story; from rags to riches.”

Growers in the Okanagan area fruit industry continue to make big investments in land and new equipment, but it can be challenging. Many children have chosen other careers, land prices have soared and provincial land policies have left a checkerboard pattern of agricultural land and urban development that adds to the logistical challenges of farming.

Punjabi families are among those willing to invest, expand and thrive on small margins in that challenging environment, and thus have lasted in the fruit industry, Sandher said.

Sukhpaul Bal, a cherry grower in Kelowna, agrees, especially with Joy’s premise about the Punjabi connection to land. The fourth-generation Canadian grower recalls family stories about how property, more than wealth, brought status to families in the agricultural regions of Punjab.

“Something that drives Sikhs and Indo-Canadians is owning property — and especially farm property,” he said.

Mingling of work and culture

Farming requires a large support network where work, family and culture mix. Bal’s three younger siblings all have separate careers but still contribute to the farm work in ways that allow for an intersection of past and present, tradition and technology.

On one hand, his family typifies modern farming.

He speaks three languages. They own and operate a progressive cherry production business with multiple orchard sites, foreign worker housing and an upgraded packing line with meeting rooms and offices overlooking the city and Okanagan Lake.

Sukhpaul supervises the production operations, while his wife, Varinder Kaur, and other family members help in a café, store and bed-and-breakfast built near the packing house, as a way to diversify for the future.

Sukhpaul, who holds a bachelor’s degree in international relations, serves as the president of the BC Cherry Association, sits on the board of other agriculture organizations and has been known to meet with buyers in Berlin and Hong Kong.

His outgoing son, 3-year-old Mehtaab, suggested calling cartoon characters “Paw Patrol” to put out several forest fires surrounding the lake in July last year. They also have a 1-year-old boy named Arjun.

However, tradition runs deep, too. Their marriage was not arranged but their courtship certainly was.

Taking his parents’ advice, Bal let his mother ask around among their Indian relatives and friends for a young woman his age from another family for whom marriage meant working alongside a spouse within the family business.

Kaur’s name came up. He flew to India and spent two weeks getting to know her, proposed and flew back a year later to marry her in India.

“It was kind of a leap of faith,” he said. “One day you’re single … the next day you’re engaged.”

Kaur stayed in India another year to obtain a visa before joining him for their life in Canada. Besides her work in the café, she enjoys her role as “a busy mom,” and takes her family to the Sikh temple roughly once a month, she said. She is now applying for her Canadian citizenship.

“My family is really good here,” said Kaur, who plans to change her last name to Bal after earning her Canadian citizenship later this year.

Sandher family history

Bill Sandher was 18 when he moved from Punjab to the Okanagan Valley in 1982 with his father and younger brother, seeking better economic opportunities. His older sister, by then a citizen, sponsored them. His mother had died in India a few years earlier.

Jobs were not plentiful then and the family bounced around the communities of the British Columbia interior picking berries and vegetables, pruning fruit trees and working in restaurants. But his father liked Vernon, at the north end of the valley, which had a gurdwara, or temple, where he could mingle with other men his age and ethnic background.

In 1989, apple grower Andy Hartman, in Kelowna, offered to let the brothers farm his land on lease. Prices were low and work was hard. Several times they considered moving on from agriculture, Sandher said. In 1995, frustrated and now married, Sandher made up his mind to replant the entire orchard. At the time, the provincial government helped subsidize replant projects.

By then, Hartman had, over the years, taught the brothers about chemical sprays and horticulture, and he realized his three children were not interested in farming. With only a handshake sealing the deal, he agreed to sell the farm to the Sandhers for no payments for 12 years.

Eventually, the Sandhers found success and expanded. The family started its own nursery in 1994, started growing cherries in 2000, built a cherry packing facility in 2006 and an apple packing facility in 2016, all the while expanding acreage. They also created their own cherry brands, Big Hat and Kushi, the Punjabi word for “happy.”

Bill Sandher was hesitant to invest five years ago, as his two sons reached adolescence and showed more interest in hockey and basketball than farming. Today, in their 20s, they are all in.

One reason they stayed, the brothers said, is because their dad listens to them and allows them to make decisions, something not all Indo-Canadian elders do, they said. They talked him into purchasing Unitec optical sorting equipment and purchasing two European orchard platforms.

Their mother and Bill’s wife, Sukhi Sandher, also is involved in the business nearly every day.

“My mom’s a genius at this stuff, too,” said Gurtaj, Sandher’s older son.

Sandher admits to working hard but doesn’t think he or other Punjabis are the only ones. “There are many who work hard,” he said. “There are many people who are smart. That doesn’t mean they’re going to have success in business.”

To this day, Sander considers the trust and kindness of Hartman, the man who sold him his first orchard on a handshake, the key ingredient in his family’s success.

“That was my luck,” he said. “I wasn’t smart. I wasn’t different than anybody else.” •

—by Ross Courtney

[…] Click here to view original web page at goodfruit.com […]