Editor’s note: Story has been updated to reflect exception to Kitzke Cellars’ Candy Mountain sourcing, which the Good Fruit Grower learned of after publication.

Two Washington wine grape growing regions became official American Viticultural Areas in September.

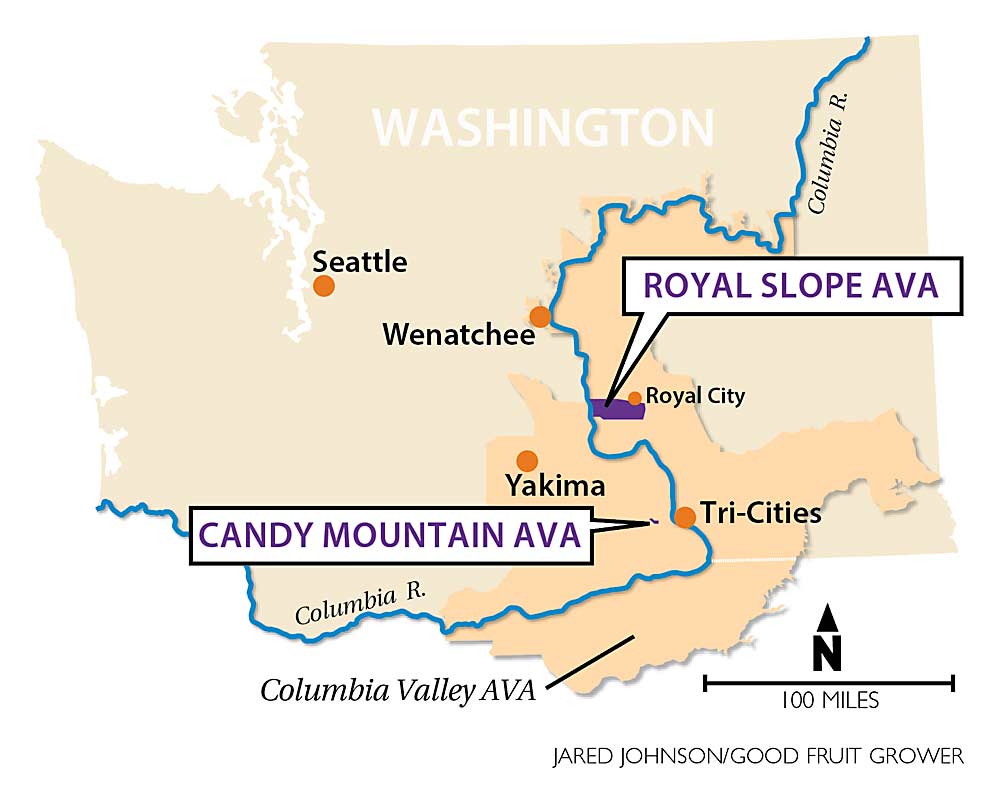

Royal Slope, in the Columbia Basin, received the federal designation on Sept. 2 while Candy Mountain, near the Tri-Cities, got the nod on Sept. 25, becoming the 15th and 16th American Viticultural Areas, or AVAs, in the state and the most recent additions since the Lewis-Clark Valley AVA in 2016.

To qualify as an AVA, a wine grape growing region must convince the U.S. Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau it has distinguishable climate, soil, elevation and physical features. California has 139 AVAs, Oregon 21.

Southern exposure and an elevation that allows an array of varieties characterize Royal Slope.

Located on a 30-mile-long east-west ridge above the Columbia Basin in Central Washington, the Royal Slope AVA has an elevation — and therefore a climate — suited for a wide palette of wine that is sometimes described as fresh, fruity and even “crunchy,” in the words of one winemaker.

Winemakers and viticulturists from the Royal Slope area have been working on the designation for nearly five years, said Josh Lawrence, owner of Lawrence Vineyards and Gard Vintners. “It was a long time coming,” said Lawrence, the primary advocate for the AVA.

The Royal Slope AVA covers 156,389 acres, wholly within the Columbia Valley AVA, and hosts 1,900 acres planted with 20 different varieties of wine grapes, according to the Washington State Wine Commission. The majority of the area’s soils are formed of windblown silts, or loess.

Royal Slope marks the industry’s increasing curiosity about cooler areas, said Alan Busacca, a retired Washington State University soil scientist who has authored several AVA applications, including Royal Slope.

“There’s a renewed interest in cooler conditions,” said Busacca, also a wine grape grower.

Though not the highest AVA in the state, Royal Slope has an elevation range between 610 feet and 1,756 feet, giving it just enough rise over the surrounding area to provide cooler days and nights than some of its warmer Washington siblings that are famous for plenty of heat to ripen late-season red varieties such as Cabernet Sauvignon. Royal Slope’s lower altitudes do the same, but its higher levels extend the growing season, delaying ripening and retaining some of the fruit’s natural acidity.

“We talk about it as crunchy red fruit or fresh fruit,” said Erica Orr, a Woodinville winemaker who uses grapes from the Royal Slope AVA among her portfolio of wine labels. Grapes from warmer areas have characteristics of “blackberry jam, soft and cooked,” she said. Both have their place in quality wine, she said.

At 815 acres, Candy Mountain is the smallest AVA in the state, with 110 acres currently planted to vineyards, according to the Washington State Wine Commission.

Candy Mountain is part of a chain of four arid hills. The other three are Red Mountain, Badger Mountain and Little Badger Mountain. The rise in topography gives Candy Mountain cold air drainage, while the predominantly south-facing slope enhances sunshine exposure and warms the soil in the spring.

The new AVAs will help the Washington industry as a whole, said Seth Kitzke, whose family owns Kitzke Cellars, the only winery in the Candy Mountain AVA.

“Wine is a reflection of the land it is grown on,” Kitzke said. “Having areas like Candy Mountain and the Royal Slope … help the industry distinguish premium growing areas.”

All of Kitzke Cellars’ wines come from grapes grown within the AVA, except for a limited run of Nebbiolo sourced from the Horse Heaven Hills.

Like many of the state’s AVAs, the two new ones are carved from larger AVAs. Royal Slope is part of the greater Columbia Valley AVA, a massive region of more than 11 million acres and one of the state’s first designations. Candy Mountain is part of the broader Yakima Valley AVA, itself part of the larger Columbia Valley AVA.

Five more Washington AVAs are in the application process: White Bluffs, The Burn of Columbia Valley, Goose Gap, Rocky Reach and Wanapum Village. However, winemakers and growers say Washington is nowhere near having too many AVAs or diluting their meaning.

The smaller AVAs give customers more specific information about the area where the grapes in their wine were grown, said Mike Januik, another Woodinville winemaker who uses Royal Slope grapes. Shoppers want that.

“Consumers want to know the uniqueness of wine,” he said.

Lawrence, whose family has farmed the Royal Slope area since 1965, agreed.

Washington has such a vast growing region that specificity helps everybody, said Lawrence, who also raises cherries, apples and row crops. For one thing, the federal government won’t sign off on an AVA unless the area truly has distinct characteristics. Meanwhile, wineries have been asking him and other grape growers to go through the application process.

“It’s easy for growers to think their ground is unique; it’s different when wineries ask for it,” he said. “Then you take heed.” •

—by Ross Courtney

This article claims that Kitzke is sourcing all of their fruit from within the Candy Mountain AVA, but according to their own website they are sourcing Nebbiolo from Horse Heaven Hills.

You are right. I called Seth Kitzke. The Nebbiolo is a very limited run sourced from the Horse Heaven Hills. He rarely mentions it because of the small volume. The story has been updated online. Good catch.