The tree fruit industry faces pressure from everywhere.

It doesn’t just feel that way, it’s true, said David Magaña, the keynote speaker at the Washington State Tree Fruit Association Annual Meeting in December in Kennewick.

Inflation, regulatory changes, conflicting consumer demands. They all put the squeeze on producers of fresh fruit, he said. Even a declining fertility rate in Mexico tightens the screws on the Washington tree fruit industry by making migrant labor scarcer.

“I know now it’s a very complex environment,” said Magaña, vice president and senior analyst for RaboResearch Food & Agribusiness. “The equation is now more complex, but we also have more tools.”

Based in Fresno, California, Magaña specializes in the fresh produce market. He grew up a farm boy in Central Mexico, he said, but his father often picked cherries and apples near Pasco, Washington, as a migrant laborer.

Magaña slots pressures facing the fruit industry into two camps — supply and demand — that wallop from both sides.

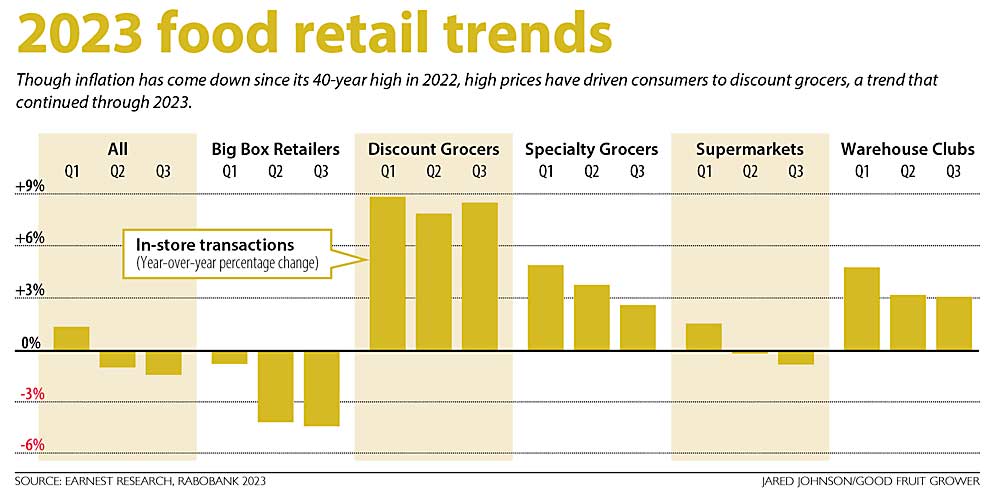

On the demand side, consumer money doesn’t go as far and people have less in savings. Inflation has slowed since its 40-year high in 2022, but prices are still rising, causing shoppers to “trade down” for cheaper items and shop at discount stores. Meanwhile, retailers are displaying smaller packages, a trend often called “shrinkflation,” he said.

That consumer focus was a favorite point for Marty Olsen, a Prosser-area grower and chair of the meeting’s organizing committee. Fresh produce is expensive for shoppers these days, even in the world’s strong economies, Olsen said.

“A premium item of fresh produce is an easy one to spend less on or eliminate completely,” he said.

Those shopping decisions affect grower returns more than anything else.

“It all starts with the consumer,” Olsen said.

Also, shoppers expect a lot and have conflicting wishes, Magaña said.

“It’s challenging to meet consumer expectations because, on the one hand, they want … year-round availability of fresh fruit, but at the same time they want it locally grown, when it’s not always possible,” he said. “They want perfect quality, but at the same time, they want it to be organic and with less use of pesticides. On the other hand, they want more convenience. But please, reduce to less plastic. We don’t want to waste all that plastic. Right? And on top of that it has to be affordable.”

In the export world, the dollar continues to grow stronger against customer currencies, such as the Indian rupee, Japanese yen and the Chinese yuan, making items such as fruit more expensive for international shoppers. High container rates in many ports don’t help, either. Thus, exports of fresh apples have decreased over the past four years.

As for supply, growers face the constraints of water, labor and regulations. High interest rates make it harder for producers to innovate and reinvest. Meteorologists are forecasting an El Niño drought in the Northwest.

Immigration provides less help these days, he said. Mexico’s improving standard of living and declining fertility rate have slowed migration. In the 1960s and 1970s, the average Mexican family had almost seven kids per family. Today it’s about two.

“I can relate to that,” he said. “I had seven siblings, and I had just two kids.”

Meanwhile, Mexican farms face their own farm labor crisis with wages rising even faster than America’s, he said.

International competition should heat up, and shoppers will soon expect fresh cherries in the market year-round, the way they do blueberries. Magaña wouldn’t be surprised if Peru, a growing exporter of blueberries and avocados, starts planting cherries on a massive scale over the next five to 10 years.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture estimates that for every dollar spent on food in America, 15 cents makes it back to the grower.

So, pressure yes. But a few bright spots exist.

Trucking and shipping costs have come down from their peak in early 2022. India reduced its tariffs on apples in 2023. In Mexico, one of the U.S. fruit industry’s largest export markets, the peso has gained in strength against the dollar to make products such as apples, pears and cherries more affordable for shoppers there.

Then, there is a culture of innovation in the fresh produce space. Generation Z has the highest level of education in history and will help foster change, he said.

“I’m still optimistic about the future of agriculture in general, and fruit production in particular, given all the innovation that we’ll see happening in the next 15 years,” he said.

Magaña’s keynote was affirming to his audience of growers, who have been feeling the pinch for a few years, said Jon DeVaney, president of the Washington State Tree Fruit Association.

“David Magana’s keynote speech confirmed with economic data what most growers already felt: We are in a fiercely competitive international food market that limits opportunities to achieve increased pricing even as production costs are subject to rapid inflation,” he said.

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment