On an ordinary weekday, Dr. Ian Merwin is a Cornell University teacher and researcher who has put his mark on the orchards of New York—and elsewhere—because of his work with orchard floor management systems, including nutrient dynamics, soilborne diseases, ground cover, and weed control.

But in the evenings and on weekends, Merwin puts on the work clothes of an apple grower and tends an unusual orchard on his 64-acre Black Diamond Farm near Trumansburg, New York. There, he grows the apples and other fruits that he and his wife, Jackie, consider to be distinctive and top quality—some of them old and rare, and others new but not widely known, such as disease-resistant apples from the Cornell and PRI (Purdue-Rutgers-Illinois) fruit breeding programs.

From summer through early winter, Ian, Jackie and their daughter Erica sell 88 varieties of apples, and another 100 or so varieties of peaches, pears, plums, cherries, grapes, and blueberries, at the Ithaca Farmers’ Market, through an on-farm CSA, and at local restaurants and co-op markets. Niche market varieties are their hallmark, and those that don’t sell well or generate excitement with customers get pulled from their orchard or topworked and converted with some other scion. “We’re constantly fine-tuning our variety mix,” Merwin said. “We take out whatever doesn’t sell. There are too many great fruit varieties to grow or sell anything that you’re not excited about!”

At the market, they have a rule: “Everybody gets to taste any apple that we offer,” he said. Not all on one day, of course. Every weekend from late June to early December, they bring to market whatever is ripe that week. Early in the season, there are just a few of the early varieties, plus the cherries and blueberries—which they grow partly to diversify their selections beyond the main crop, apples. By October, they often have 25 varieties each weekend—almost too many, he says, because the different varieties start to compete with each other.

Jackie maintains a database and e-mail list with details on the specific preferences of loyal customers, and sends out e-mailings on Thursday each week, highlighting what’s at peak flavor and what will be on the truck each weekend as the season progresses. “Come and get them early,” they say, “while they last….”

Their orchards and vineyard are about eight acres, and the apples they grow can be roughly categorized into four distinct kinds.

Cider apples

“There’s a small section of the orchard devoted to antique French and English apples grown for traditional hard cider blends,” according to the farm’s Web site, www.incredapple.com. “They have interesting names like Brown Snout, Foxwhelp, Fillbarrel, Magog Redstreak, Porters Perfection, etc. They’re not for eating fresh, but for premium hard ciders, they’re the best.”

Merwin is an expert on hard ciders and works with growers in New York and elsewhere who are trying to redevelop that industry in the United States. Today, France and England are the leading sources of both cider varieties and knowledge. The U.S. hard cider tradition was largely stamped out by Prohibition 80 years ago and has never really recovered nationally, but it is making a comeback in the Northeast, Northwest, and Mid-Atlantic regions.

In the cider apple part of his orchard, there are different categories of varieties grown for their acid content, their tannin content, their sugar content, or other qualities such as intense aromatics or watercore (which can be advantageous for cider-making). The cider apples can be further classified as sharps, bittersharps, bittersweets, and sweets, and premium ciders should be a blend of all these types, Merwin said.

Disease resistant

Then there are the apple scab-resistant varieties, mostly from the Cornell and PRI programs. These include GoldRush, William’s Pride, Crimson Crisp, Liberty, and Sundance (a sister of GoldRush). Many of the russet apples also have some resistance to fruit scab. Merwin likes the disease-resistance idea because it reduces the need for sprays—but these apples must also pass the customer taste test.

“I won’t grow some of these again,” he said, listing Enterprise (“rubbery skin”), Redfree, Jonafree, and Priscilla. They recently planted some additional disease-resistant types such as the Czech variety Topaz, and the PRI release Winecrisp, to see how they fare at the market and in the orchard.

Merwin is enthusiastic about GoldRush. Between his home plantings and a research block he planted at Cornell in 1994, Merwin has about 1,200 trees of that variety growing on M.7 rootstock, and it is one of their most popular varieties. It matures late—but not too late for upstate New York—and is disease-resistant. “After a few months in regular storage, GoldRush after-ripens to a golden perfection, with rich aromas and an intense blend of sweetness, crunchiness, and crisp acidity,” Merwin said. “It is a very productive and precocious low-vigor variety that needs a strong rootstock,” he said. “It’s a really unique apple. People start asking for them a month or more before we pick them. I think it grows better in northern regions than in hotter areas because it needs a few October frosts to ripen properly. It’s usually the last one we pick, about November 1.”

Heirlooms

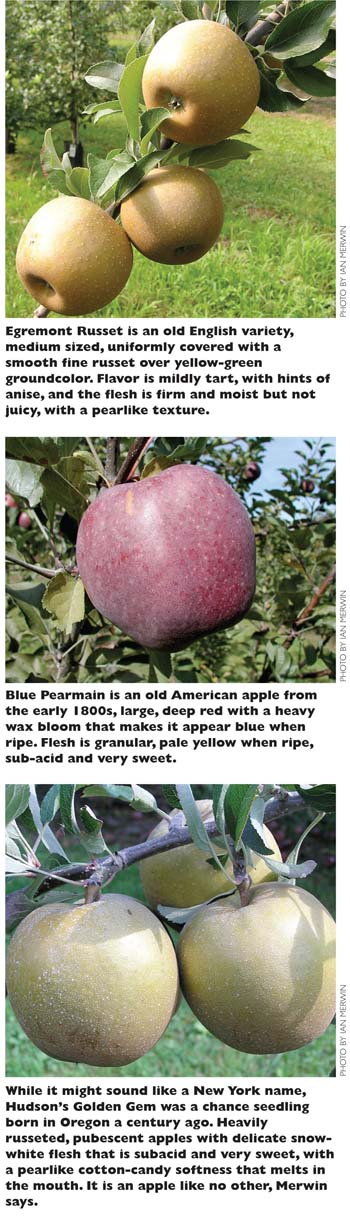

The third apple group is heirlooms—apples that are old or rare, and have interesting qualities. Their customers love the heirloom russet apples, like Hudson’s Golden Gem, Ashmead’s Kernel, Golden Russet, Zabergau Reinette, and Egremont Russet.

They also like Newtown Pippin and Winesap, and a relatively recent but little known apple from Minnesota—Keepsake—that was one parent of Honeycrisp (Merwin says that’s where Honeycrisp got its texture and juiciness). He has a love-hate relationship with an old local apple Tompkins King, which was named after Tompkins County, where Cornell is located, and was an old-time favorite for cider-making because the apple is literally oozing with watercore most years.

The Merwins also grow the old English variety Cox’s Orange Pippin—and as many of its offspring as they can obtain (for example, Holstein Cox and Karmijn de Sonneville). Cox Orange Pippin was discovered in 1825, and like McIntosh and Golden Delicious, Cox Orange has earned a stellar reputation as a great parent for apple breeders, generating many distinguished offspring over the years.

“Some of these old varieties have earned a new lease on life,” Merwin said. “They are in high demand at farmers’ markets all around the country, where they fetch prices comparable to Honeycrisp.”

Must haves

The fourth category of apples in the Black Diamond orchards is the “must haves,” the apples you just have to have at your markets. So they grow Honeycrisp, which is in high demand despite having “every problem an apple could have.” They also grow Ginger Gold, Gala, Fuji, Jonagold, a few good strains of McIntosh, and its offspring Macoun, Cortland, and Empire, all of which are “must haves” in New York State, he said.

Leave A Comment