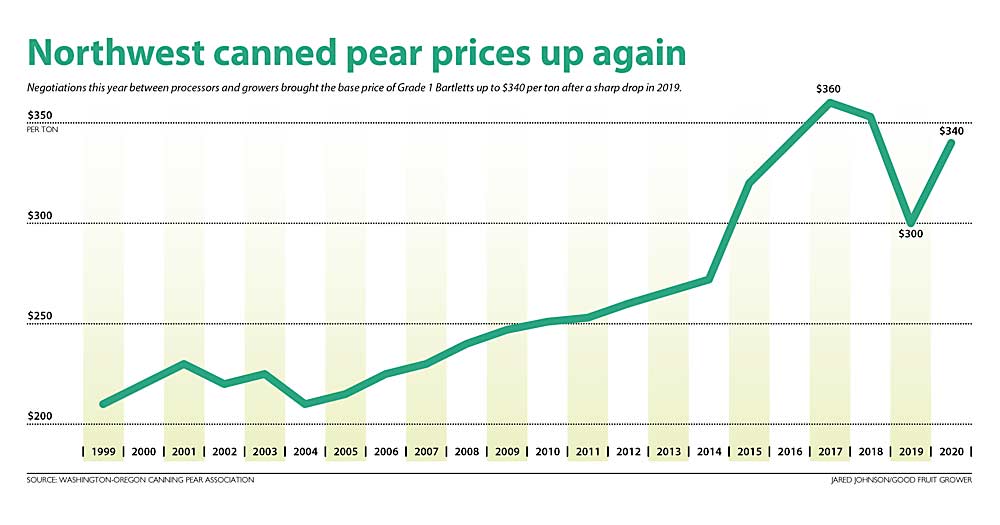

Graphic: Jared Johnson/Good Fruit Grower)

After a new Washington state law compelled pear processors to negotiate with a grower organization, the industry has settled on a collective price for canned pears considerably higher than last year.

This year, the state’s two remaining processors have agreed to purchase canning Bartletts for $340 per ton base price from growers in Washington and Oregon.

That’s higher than the $300 per ton average growers received in 2019, after one processor closed and another decided to negotiate directly with individual growers instead of through the Washington-Oregon Canning Pear Association. However, supply and demand probably contributed more to this year’s price increase than the new law, some industry officials said.

“The primary reason is prices were so low last summer that we lost growers and acreage,” said B.J. Thurlby, president of the Washington-Oregon Canning Pear Association.

For years, the association negotiated (under a federal marketing order) a collective price with Washington’s largest canner, Del Monte Foods in Yakima, while Neil Jones Food Co. in Vancouver and Seneca Foods in Sunnyside followed suit. Canning pear prices rose steadily from $210 per ton in 1999 to a high of $360 in 2017.

Since those days, Chinese imports of canned pears have increased in volume, while American tastes have shifted away from cans and toward fresh produce. In spring 2019, Seneca announced it would close after that year’s harvest, and Neil Jones started the season by seeking individual price deals with growers. Later in the year, Neil Jones announced a price floor of $315.

To adjust to the changes over the years, many producers have steadily removed pears to the tune of hundreds of acres, though Thurlby did not have an exact count. It was enough to take the volume from 100,000 tons per year to 80,000 tons per year, said Steve Carlson, field manager for Del Monte’s Northwest operations.

This year, the association convinced the Washington State Legislature to alter state law to include the group as an accredited negotiating agent on behalf of the canning pear producers, much as other groups are for corn and potato producers. State Rep. Bruce Chandler, a Republican from the Yakima Valley with his own fruit orchard, sponsored the legislation.

That by itself doesn’t guarantee growers a better price, but it requires the state’s two remaining processors, Del Monte and Neil Jones, to at least negotiate with the Yakima-based organization.

“It’s a big step where they at least have to come and talk to us,” said Adam McCarthy, a Hood River, Oregon, pear grower and chair of the association.

From now on, if the two sides don’t reach a deal, the state director of agriculture would step in, though the specifics of that role are still undetermined, Thurlby said.

The price increase is a sign that supply and demand is reaching a better equilibrium, Carlson said, though he called supply “still slightly long.”

The coronavirus this year threw another wrinkle into pear prices, with fewer restaurants and food service companies buying, he said. •

—by Ross Courtney

Leave A Comment