The full impact of the heat dome that hit the Pacific Northwest in late June — bringing a week of record-setting temperatures that baked apples in unprotected blocks, sent cherry growers scrambling to harvest before ripe fruit melted and caused huge losses for blueberry growers west of the Cascades — won’t be clear until next year.

Northwest wine grape vineyards seemed to weather the heat fine. For other crops, though, the toll of the heat stress may appear in the form of smaller fruit, reduced apple and pear packouts, cherry bud doubling, less apple return bloom and even stunted tree growth.

It is already clear that the heat put apple cooling systems to the test. And not every approach passed.

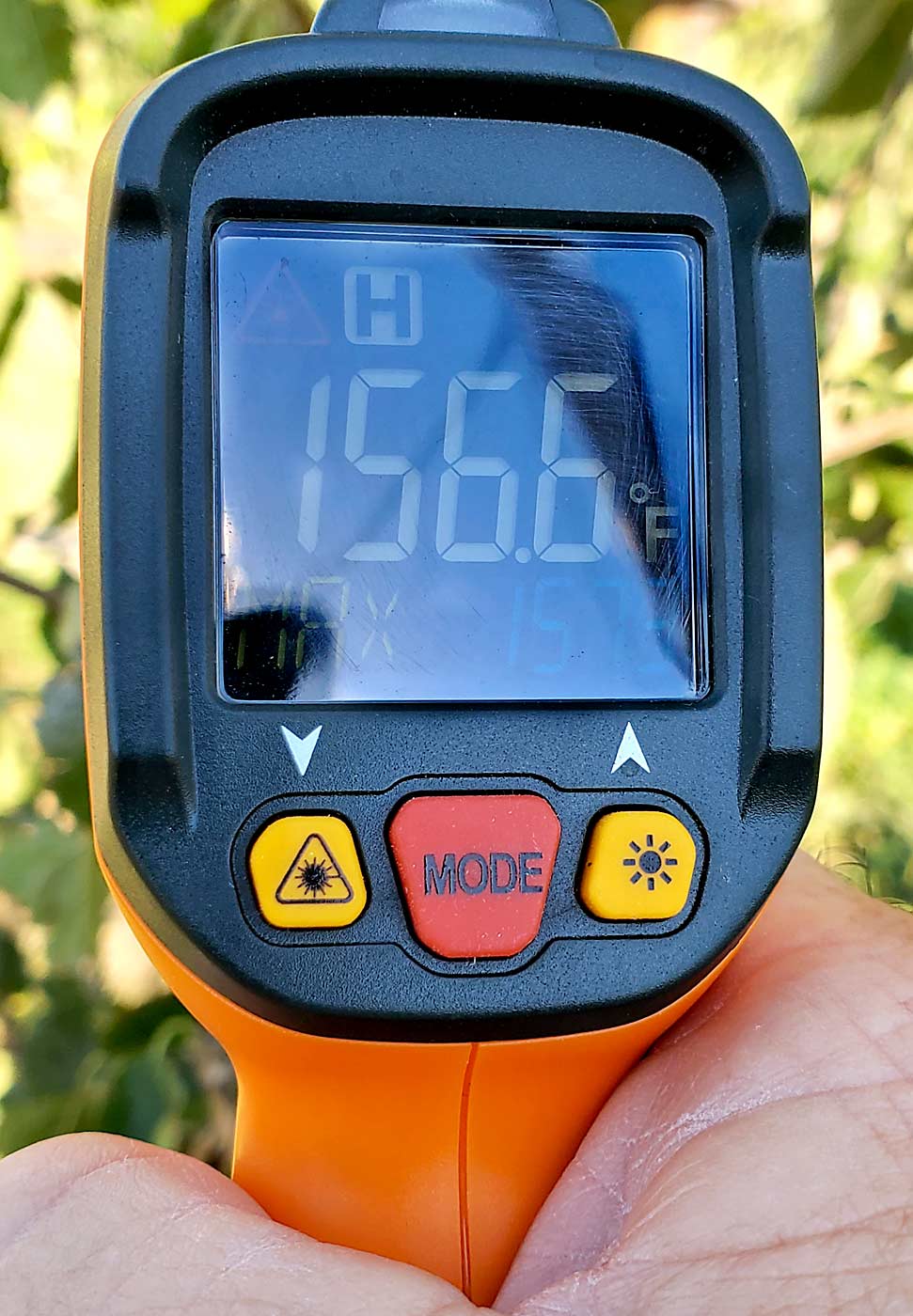

That’s the takeaway from horticulturist Byron Phillips of Wilbur-Ellis Co., who visited Quincy, Washington-area orchards in over 110-degree weather to measure fruit surface temperatures under a variety of protective techniques, including netting, rotating cooling, mist cooling and spray-on sun protectant, along with unprotected blocks.

“I went in thinking: This is the year the investment (in netting) is going to pay off,” Phillips said. “But for some, it did not.”

He found fruit surface temperatures ranging from 80 degrees in a fog-cooled block to 163 degrees in an untreated block where he would “bet money that the sap boiled” in some extremely stressed V-trellised Galas, he said. For context, fruit surface temperatures above 114 degrees can lead to sunburn browning, while sunburn necrosis occurs when fruit exceeds 120 degrees for at least 10 minutes.

“Honestly, we haven’t seen much sunburn browning. The apples just baked; it’s all sunburn necrosis,” Phillips said.

Shade cloth apparently ranges in quality, he said. In some blocks, shade cloth with a tight weave was able to keep fruit below 100 degrees, while blocks covered by shade cloth with a looser weave experienced fruit temperatures from 116 to 129 degrees. Different sprayable protectants also showed varied effectiveness.

Fogging systems consistently kept orchards the coolest, Phillips said, converting him to a believer in the microcooling approach. In orchards with rotating overhead cooling in an on/off pattern, fruit surface temperatures nearly reached 120 degrees during the 30-minute off period, he said.

This fall, apple growers will harvest very different classes of fruit, he said. The blocks that were well protected with shade netting or fogging will probably behave like normal fruit. “But the fruit that was poorly protected, that’s a completely different class of fruit we are going to want to segregate at receiving,” he said. “We just don’t know what it means for fruit condition, postharvest disorders and a whole host of other things.”

Washington State University postharvest physiologist Carolina Torres agreed.

While growers discard obviously sun-damaged fruit, there are invisible consequences to all the sun and heat stress that link to a wide variety of storage disorders, she said, including sun scald, internal browning and lenticel issues.

“The heat we already had, it definitely increases the environmental stress, and that may lead to earlier harvest,” she said. “In a warmer season, fruit ripens faster. Even though you are harvesting with the same maturity indices, it’s a different piece of fruit.”

Data she’s collected over the previous two seasons, comparing the postharvest performance of fruit from warmer and cooler growing sites, shows distinct differences in disorder incidence. Applying 1-MCP and chilling can slow down the accelerated ripening caused by hot growing conditions, but 1-MCP can’t be used on organic fruit. So, Torres designed her trial to look at organic postharvest practices, but the data also speaks to how growing season climate impacts fruit quality.

“In a warmer season, in general, it’s more important to use 1-MCP to stop that process (of rapid maturation) and chill that fruit faster to bring the metabolic processes down,” she said.

How the 2021 crop will store is the big unknown, said Scott McDougall of McDougall and Sons of Wenatchee.

“With cooling systems and sunburn spray protectants, at this point, it doesn’t look too bad,” he said in late July. “And it was early enough that there was a fair amount of thinning to do, so we were able to thin off the worst sunburn.”

While most apple growers don’t expect to need cooling measures in June, the fact that the heat hit when the fruit was still “a smaller target” seems to have helped too, McDougall said.

He’s also a fan of the new generation of fog cooling, especially for Honeycrisp and sites with heavier soils, to reduce waterlogging. McDougall and Sons uses netting over its later-harvesting varieties but found that it held back color on the early varieties — and pulling back netting to get that color in August or early September was a recipe for sun damage.

Even in the blocks with netting, such as those covered by a louvered system protecting the sun-exposed west side, “we’ll still use fogging for evaporative cooling,” he said.

While McDougall and other Eastern Washington growers said it looked like their cooling measures managed to head off severe damage, in Western Washington, orchards were entirely unprepared for sustained temperatures over 110.

“The Honeycrisp looks like it’s been cooked with a blowtorch,” said Griffin Berger of Sauk Farm in Concrete, Washington. Across all his high-density apples, he estimates a 30 percent crop loss, while the older blocks with larger canopies sustained about 10 percent losses. Meanwhile, his peaches and grapes did just fine.

The only protective measure he had was kaolin clay for the apples. At 114 degrees, plus humidity, even with the clay coating, he measured fruit surface temperatures over 140 degrees.

“We think in all our future blocks we’ll have to put in shade netting,” he said, adding that the water supply available would limit the acreage they could protect with evaporative cooling. “We’ve been farming at this site for 14 years and the weather has gone from more mild to more extreme. Even if this heat never happened again, the risk of the potential future crop loss would pay for the installation. That’s how we have to look at it.”

—by Kate Prengaman

Leave A Comment